EXPERT OPINION — For about a week we experienced significant controversy over the first military attack on alleged narco-trafficker small boats off the coast of Venezuela (and later Ecuador). The controversy began with news that the Secretary of Defense had ordered the Special Operations Command Task Force commander to, “Kill them all.” This was linked to reports that the boat was attacked not once, but twice; the second attack launched with full knowledge that two survivors from the first attack were hanging on the capsized remnants.

Critical commentary exploded, much of it based on the assumption that the “kill them all” order had been issued, and that it was issued after the first strike. Even after the Admiral who ordered the attacks refuted that allegation, critics continued to assert that the attack was, ‘clearly’ a war crime as it was obviously intended to kill the two survivors.

The public still does not know all the details about these attacks. What is known, however, is that Congress held several closed-door hearings that included viewing the video feed from the attacks and testimony from the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of State, and the Admiral who commanded the operation.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reaction to these hearings has crystalized along partisan lines. Democratic Members of Congress and Senators have insisted they observed a war crime and called for public release of the video. Republicans, in contrast, have indicated they are satisfied that the campaign is based on a solid legal foundation and that nothing about the attacks crossed the line into illegality.

What is less obvious than the partisan reaction is how what began as a problem for the administration has ended up becoming a windfall. When Senator Roger Wicker, Chairman of the Armed Services Committee, announced after the second closed door briefing that he was satisfied with the administration’s legal theory and saw no evidence of a war crime, it provided a signal to the administration that this Congress is not going to interfere with its military campaign. Democrats will try: they will continue to demand hearings, they have asserted violation of the War Powers Act and propose legislation requiring immediate termination of the campaign, and they will continue to insist the U.S. military has been ordered to conduct illegal killings. But so long as the Republican majority is tolerant of this presidential assertion of war power, there is virtually nothing to check it. This so-called ‘double tap’ tested the political waters, and it turns out they are quite favorable for the President.

What national security news are you missing today? Get full access to your own national security daily brief by upgrading to Subscriber+Member status.

From a legal perspective, the reaction to this incident has reflected overbreadth and misunderstanding from both ends of the spectrum. For example, characterizing the second attack as a war crime – or rejecting that conclusion – implicitly endorses the administration’s theory that it is engaged in an armed conflict against Tren de Aragua, an interpretation of international law that has been rejected by almost all legal experts. Equally overbroad has been the assumption that the second attack must have been intended to kill the survivors from the first attack – an assumption that renders that attack nearly impossible to justify, even assuming it was conducted pursuant to a valid invocation of wartime legal authority. But even release of the video would be insufficient to answer a critical question in relation to this assumption: was the second attack directed against the survivors, or against the remnants of the boat with knowledge it would likely kill the survivors as a collateral consequence? Only the Admiral and those who advised him can answer that question. And if the answer is, ‘the remnants, not the survivors’, other difficult questions must be addressed: what was the military necessity for ‘finishing off’ the boat? And, most importantly, why wasn’t it operationally feasible to do something – perhaps just dropping a raft into the water – to spare the survivors that lethal collateral effect?

But the true significance of this incident and the reaction it triggered extends far beyond the question of whether that second attack was or was not lawful; it is the implicit validation of the foundation for the legal architecture the administration seems to be erecting to justify expanding the conflict to achieve regime change in Venezuela. In this regard, it is important to recognize that the Trump Administration is implicitly acknowledging it must situate its campaign and any extension of this campaign within the boundaries of international law, even as it seeks to expand them beyond their rational limits. Understanding this consequence begins with two essential considerations. First, the Trump Administration’s consistent invocation of international legal authority for its counter-drug campaign - albeit widely condemned as invalid – indicates that any expansion of this campaign will be premised on a theory of international legality. Second, that theory will have to align with the very limited authority of a state to use military force against another state enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations.

That limited authority begins with Article 2(4) of the Charter, which prohibits a state’s threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any other United Nations member state. This prohibition is not, however, conclusive. Instead, the Charter recognizes two exceptions allowing for the use of force. First, military action authorized by the Security Council as a measure in response to an act of aggression, breach of the peace, or threat to international peace and security. Such authorizations have been used since creation of the U.N., one example being the use of force authorization adopted in 2011 to establish humanitarian safe areas in Libya; the authorization that led to the Libyan air campaign. The reason such authorizations have been infrequent is because any one of the five permanent members of the Security Council (the United States, United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia) may veto any resolution providing for such authorization for any reason whatsoever. It is inconceivable the U.S. could garner support for such authorization to take military action in and/or against Venezuela, much less even seek such an authorization.

The second exception to the presumptive prohibition on the threat or use of force is the inherent right of individual and collective self-defense enshrined in Article 51 of the U.N. Charter. That right arises when a state is the victim of an actual or imminent armed attack. Furthermore, the understanding of that right has evolved in the view of many states – and certainly the United States – to apply to threats posed by both states and non-state organized armed groups like al Qaeda.

Subscriber+Members get exclusive access to expert-driven briefings on the top national security issues we face today. Gain access to save your virtual seat now.

From the inception of this counter-narcotics campaign the Trump administration has asserted that the smuggling of illegal – and all too often deadly – narcotics into the United States amounts to an ‘armed attack’ on the nation. This characterization – coupled with the more recent designation of fentanyl as a weapon of mass destruction – is obviously intended to justify an invocation of Article 51 right of self-defense. As with the assertion that TdA is engaged in an armed conflict with the United States, this invocation has been almost universally condemned as invalid. But that seems to have had little impact on Senators like Wicker or Graham and other Republicans who have indicated they are satisfied that the campaign is on solid legal ground.

To date, of course, the campaign based on this assertion of self-defense has been limited to action in international waters. But President Trump indicated in his last cabinet meeting that he intends to go after ‘them’ on the land – ostensibly referring to members of TdA. So, how would an assertion of self-defense justify extending attacks into Venezuelan territory, and what are the broader implications for potential conflict escalation?

The answer to that question implicates a doctrine of self-defense long embraced by the United States: ‘unable or unwilling.’ Pursuant to this interpretation of the right of self-defense, a nation is legally justified in using force in the territory of another state to defend itself against a non-state organized armed group operating out of that territory when the territorial state is ‘unable or unwilling’ to prevent those operations. It is, in essence, a theory of self-help based on the failure of the territorial state to fulfill its international legal obligation to prevent the use of its territory by such a group. And there have been numerous examples of U.S. military operations justified by this theory. Perhaps the most obvious was the operation inside Pakistan that killed Osama bin Laden. Many other drone attacks against al Qaeda targets in places like Yemen and Somalia are also examples. And almost all operations inside Syria prior to the fall of the Asad regime were based on this theory.

By implicitly endorsing the administration’s theory that the United States is acting against TdA pursuant to the international legal justification of self-defense, Republican legislators have opened the door to expanding attacks into Venezuelan territory. It is now predictable that the administration will invoke the unwilling or unable doctrine to justify attacks on alleged TdA base camps and operations in that country. But, unlike other invocations of that theory, it is equally predictable that the territorial state – Venezuela, will reject the U.S. legal justification for such action. This means Venezuela will treat any incursion into its territory as an act of aggression in violation of Article 2(4) of the U.N. Charter, triggering its right of self-defense.

In theory, such a dispute over which state is and which state is not validly asserting the right of self-defense would be submitted to and resolved by the Security Council. But it is simply unrealistic to expect any Security Council action if U.S. attacks against TdA targets in Venezuela escalate to direct confrontation between Venezuela and the U.S. Instead, each side will argue it is acting with legal justification against the other side’s violation of international law.

What this means in more pragmatic terms is that there is a real likelihood a U.S. invocation of the unable or unwilling doctrine could quickly escalate into direct hostilities with the Venezuelan armed forces. At that point, we should expect the administration will treat any effort by Venezuela to interfere with our ‘self-defense’ operations as a distinct act of aggression, thereby justifying action to neuter Venezuela’s military capability.

It is, of course, impossible to predict exactly what the administration is planning vis a vis Venezuela. Perhaps this is all part of a pressure campaign intended to avert direct confrontation by persuading Maduro’s power base to abandon him. But the history of such tactics does not seem to support the expectation Maduro will depart peacefully, or that any resulting regime change will have the impact the Trump Administration might desire. One need only consider how dictators like Saddam Hussein and Manuel Noriega resisted such pressures and clung to power even when U.S. military action that they had no chance of withstanding became inevitable. Or perhaps the administration will bypass the ‘unable and unwilling’ approach and simply initiate direct action against Venezuela to topple Maduro based on an even more dubious claim of self-defense now that he has been designated part of another foreign terrorist organization.

One thing, however, is certain: the options for extending this military campaign to Venezuela are built upon the feeble foundation that the U.S. is legitimately exercising the right of self-defense against TdA. And now, because of an attack that triggered congressional scrutiny, the administration is in a stronger position politically than ever thanks to Republican legislators endorsing this theory of international legality.

The real issue that was at stake during those closed door hearings was never really whether a possible war crime occurred, although the deaths that have resulted from the ‘second strike’ (like all the deaths resulting from this campaign) are highly problematic. The real issue was and remains the inherent invalidity of a U.S. assertion of wartime legal authority and a congressional majority that seems all too willing acquiesce to an administration that seems willing to bend law to the point of breaking to advance its policy agenda.

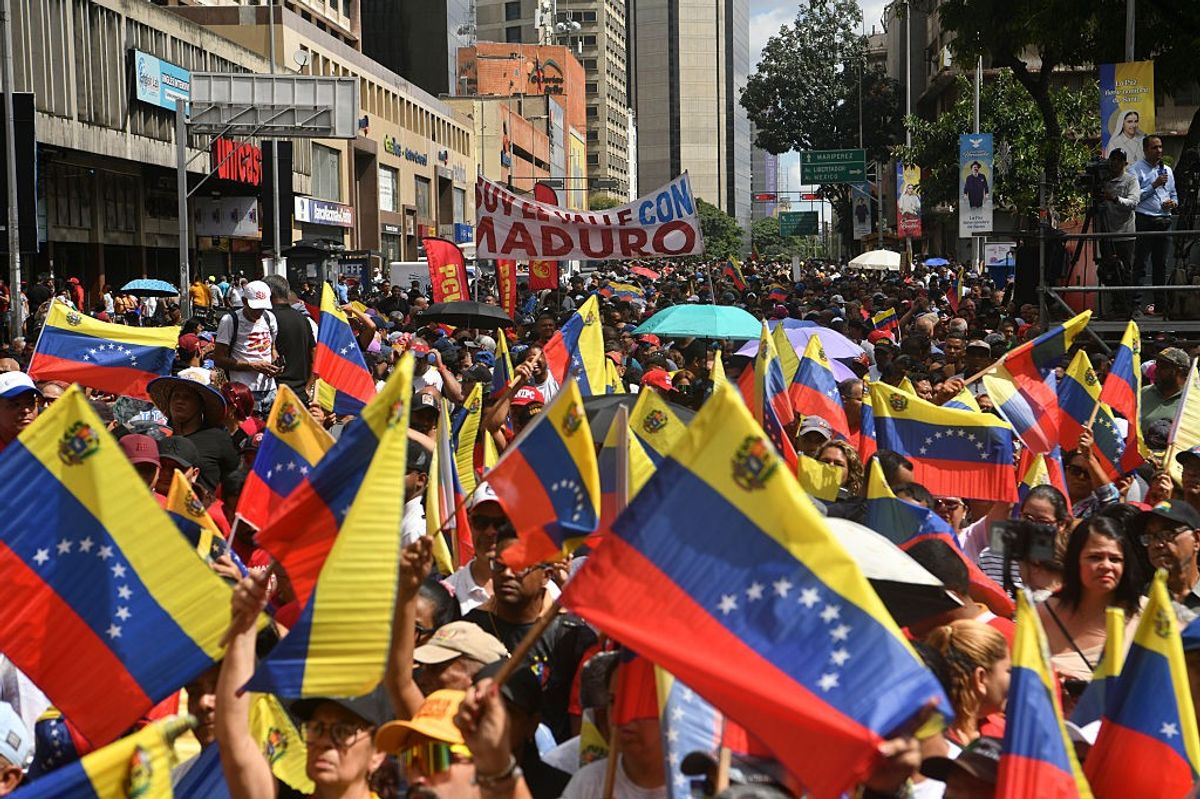

Nicolas Maduro is a tyrant who has illegitimately clung to power contrary to the popular will of the Venezuelan people. His nefarious activities and anti-democratic rule justify U.S. efforts to force him out of power and enable restoration of genuine democracy in that country. What it does not justify is constructing a legal edifice built on an invalid foundation to justify going to war against Venezuela to achieve that goal. But now that the Trump administration has tested the political waters, that seems more likely than ever.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals.

Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief, because national security is everyone’s business.