DEEP DIVE — The first bulletins hit late in the evening of February 23, 2022 in the U.S., and just before dawn on the 24th in eastern Europe: Russian troops had crossed into Ukraine; Russia was firing missiles and dropping bombs on Ukrainian cities; and Russian leader Vladimir Putin had announced a “special military operation” to “protect the people” of eastern Ukraine from what he called a “genocide” being carried out by the “Nazi” government in Kyiv. The “denazification” and “demilitarization” of Ukraine were Putin's reasons for launching the invasion, he said, though he also said his troops were entering Ukraine as “peacekeepers.”

It was a parade of falsehoods backed by massive force – the beginning of the largest conflict in Europe since World War II.

And it began 1,000 days ago.

In many ways, the Russian attack had been widely telegraphed. Roughly 200,000 Russian troops had massed along the border with Ukraine, and Putin had made menacing statements about Ukraine for months, and questioned its existence as a sovereign nation. On the other hand, many policymakers and analysts doubted Putin would actually order an invasion, given the damage it might do to the Russian federation. In one of the few pre-war headlines that has aged well, Joshua Keating wrote for Grid: “Invading Ukraine would be a terrible idea for Putin. He might do it anyway.”

Once the troops rolled in, there was another assumption, shared by many in Moscow, Washington and Brussels: Putin’s “special military operation” wouldn’t last long. The largest army in the world was roaring into a country that had no guarantee of protection or even assistance from NATO or any other allies. Putin gave a chilling warning to any nation that might contemplate helping Ukraine: any attempt to “interfere” would “lead to consequences you have never seen in history” — the first of many threats that Russia might use its nuclear weapons.

In the early hours of the invasion, the U.S. offered an evacuation route to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky – who before that day had been known as much for his skills as a television entertainer as a national leader – to which Zelensky famously replied, “The fight is here; I need ammunition, not a ride.” It was widely reported that Putin himself assumed that his “operation“ would be completed in a matter of days or weeks.

Now, 1000 days have passed since he gave the order. Ukraine has fought back in ways few had imagined possible; a previously fractured NATO alliance has united against Russia's aggression; but much western aid has come only after long debates and delays. And at the 1000-day mark, Ukraine is losing ground in the east, struggling to hold a wedge of territory in Russia's Kursk region, and many are worried that Donald Trump's return to the White House may bring a quick settlement to the war that hands territory to Moscow. Other Ukrainians — are weary of the war and willing to part with land for peace.

The Cipher Brief has covered the conflict from multiple angles since that first day. Today we mark the milestone with a data-driven look at what has happened since – the casualties and economic costs, the numbers of refugees, amounts of financial and military aid, and more. Statistics, of course, can say only so much about a war that has upended so many lives; but on the 1000-day mark, it seemed a good moment to take stock.

Honor guard members carry a coffin covered with Ukrainian flag during a farewell ceremony for Valentyna Nahorna, a medic of the 3rd Assault Brigade, with the call sign Valkyrie on November 8, 2024 in Kyiv, Ukraine. Valentyna ‘Valkyrie’ Nahorna died on the front of the Russian-Ukrainian war together with her beloved, Danyil Liashkevych, a serviceman of the 3rd Assault Brigade with the call sign Berserk. (Photo by Dan Bashakov/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images)

The military losses

The Wall Street Journal reported a grim milestone in September: around one million Ukrainians and Russians had been killed in the war in Ukraine. While it has been difficult from the war's beginning to determine the exact casualty count for either side, as Russia and Ukraine have both guarded official estimates of losses, the battlefield toll has been staggering for both sides.

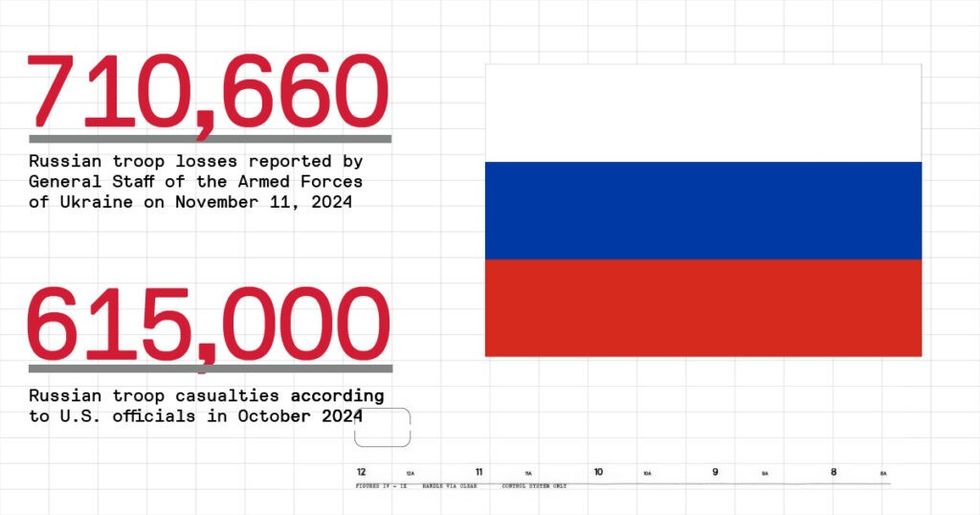

Russian losses

The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine report 710,660 dead or wounded Russian troops as of November 11, 2024. U.S. estimates in early October put Russian losses a bit lower, with officials saying Moscow has suffered as many as 615,000 casualties — including 115,000 killed and 500,000 wounded. Mediazona, a Russian independent media outlet, reported at least 77,143 confirmed Russian military deaths as of November 7, 2024.

October was by many accounts the worst month of the war for Russia’s military. The U.K.’s Chief of the Defense Staff Tony Radakin said the Russian army had lost “on average, over 1,500 people either killed or wounded every single day.” He added that those losses were incurred “for tiny increments of land.”

Observers and experts have said that Russia’s high toll — far greater than any the country has suffered since World War II — has been the result of a brutal strategy: the throwing of wave after wave of forces into the fight in Ukraine. Some Russian troops have described the experience as a “meat grinder” strategy. Despite the losses, U.S. officials say Russia continues to recruit 25,000 to 30,000 new soldiers a month. Besides regular recruits, Moscow has relied on prisoners to feed its war machine, and paid hefty salaries – well above the average wage – to lure more people to the fight. Most recently, North Korea’s deployment of troops to Russia’s Kursk region has added another 10,000 forces to the Russian side.

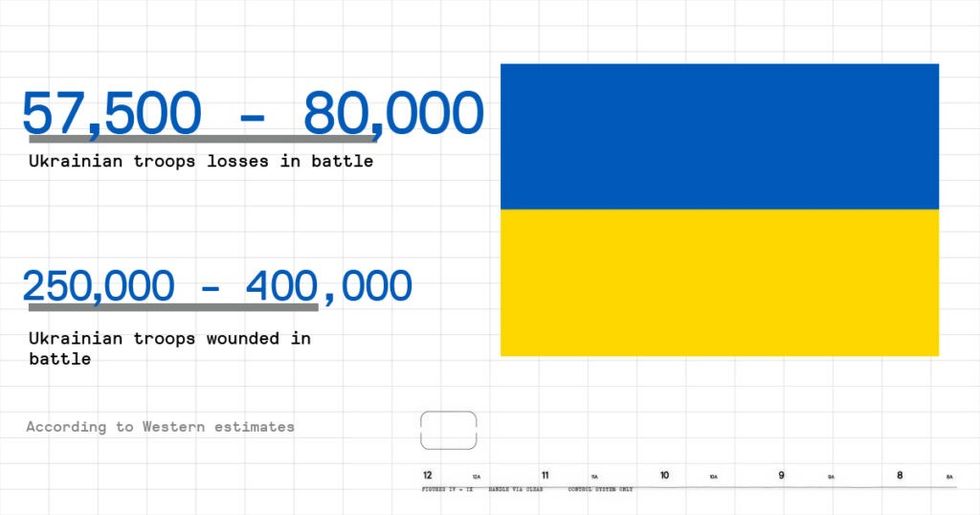

Ukrainian losses

The figures for Ukrainian military losses vary as well. The Wall Street Journal cited a confidential Ukrainian estimate in September saying 80,000 Ukrainian troops have died and another 400,000 have been wounded. The New York Times has put the figures at more than 57,700 killed and 250,000 wounded.

The country is suffering a manpower shortage of its own, and Ukraine has blamed recent gains by Russian forces in part on deficits of troops. The Financial Times reported in October that Ukraine “is struggling to restore its depleted ranks with motivated and well-trained soldiers.” As The Cipher Brief has reported, the country's recruiting efforts have been hampered by several factors: Ukraine's relatively high draft age of 25; the large number of fighting-age men who have fled the country (more on that below); difficulty paying for and equipping Ukrainians on the front lines; and the fact that its prewar population was roughly a quarter the size of Russia's.

A man holds a girl in front of burning residential building after Russian shelling with guided aerial bomb on September 15, 2024 in Kharkiv, Ukraine. (Photo by Ivan Samoilov/Gwara Media/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images)

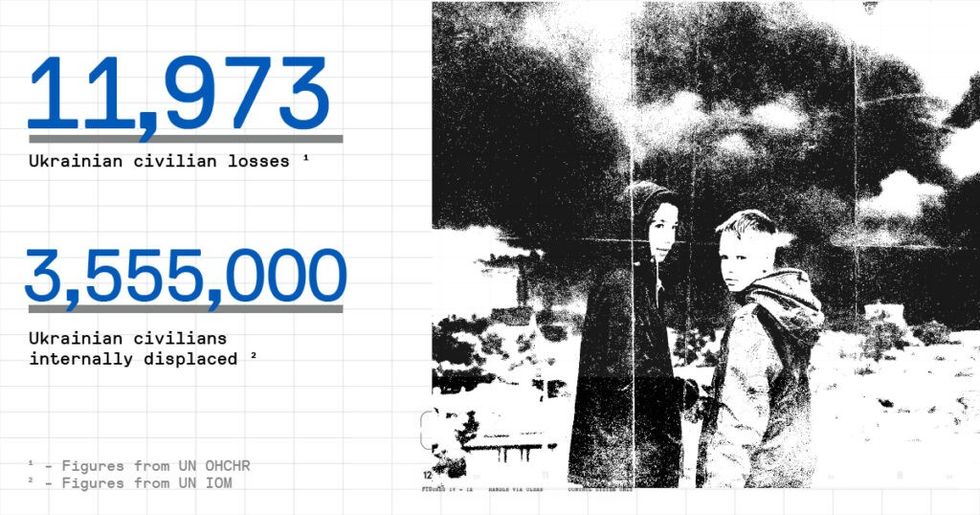

The civilian toll

Beyond the military losses for Russia and Ukraine, the war has also brought a heavy civilian toll – in this case, almost entirely on the Ukrainian side. According to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 11,973 Ukrainian civilians, including 622 children, have been killed by the fighting and Russian bombardments of civilian targets. Those figures count only victims who have been positively identified. Many believe the actual toll is far higher.

A far smaller number of Russian civilians have been killed in border fighting. The Moscow Times reported in August 2023 that 80 Russian civilians had been killed, and the Kremlin-aligned outlet TASS reported another 31 Russian civilians were killed in Ukraine’s incursion into Kursk.

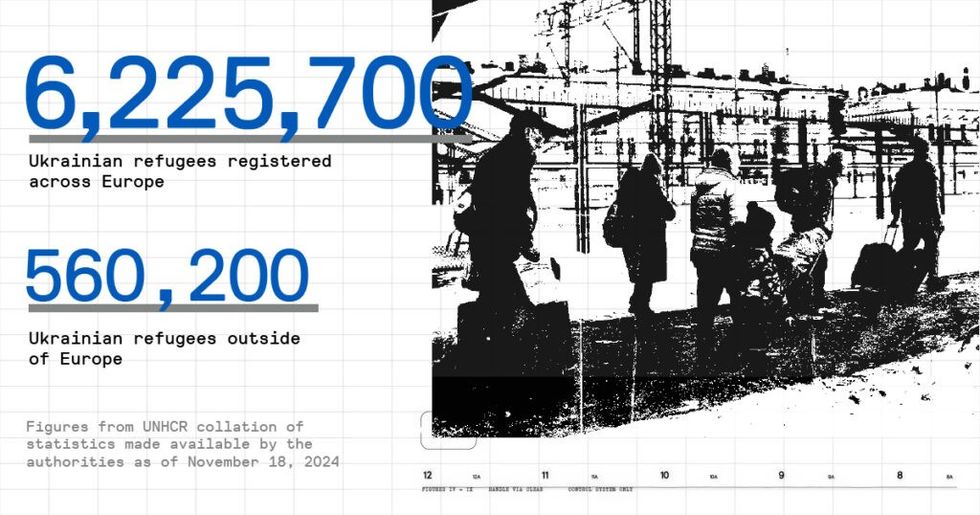

From the earliest days of the Russian invasion, the war has also pushed millions of refugees out of Ukraine, mostly into neighboring European countries. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) reports that, as of November 18, 2024, there are 6,225,700 Ukrainian refugees registered across Europe. An additional 560,200 Ukrainian refugees have been resettled outside Europe. Taken together, the figures amount to nearly a fifth of Ukraine’s prewar population. Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic have accepted the largest number of Ukrainian refugees.

According to figures from the UNHCR, around 1.2 million Ukrainian refugees are now living in Germany; Poland has accepted more than 1.5 million refugees under its Temporary Protection Directive, providing temporary residence and access to work opportunities. Roughly 980,000 of those refugees remain in Poland. The Czech Republic accepted more than 500,000 refugees, with some 380,000 living there now.

Occupied territory

In the initial thrust of its invasion, Russia pushed into northern, eastern and southern Ukraine, going so far as to reach the outskirts of Kyiv. Ukrainian forces drove Russian troops back from these initial advances, but 1,000 days into the war, Moscow still occupies around 18 percent of Ukrainian territory. After several major exchanges of territory during the first nine months of the war – and despite ferocious battles on several fronts since then – this figure has changed little since November 2022.

In September 2022, Russia declared its annexation of the Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions, though it does not fully control any of these regions. Ukraine and much of the international community do not recognize these claims. Russia also annexed Crimea in March 2014 following a disputed referendum, a claim that is also disputed by most of the international community.

Ukraine continues to hold around 200 square miles of territory inside Russia’s Kursk region, which its forces captured in an August incursion. Ukraine claimed in September that it had seized nearly 500 square miles of Russian territory at the start of the Kursk operation. Russia’s military has counterattacked, slowly retaking land, and Russian forces in Kursk are now being supported by thousands of North Korean soldiers. Media reports say it was the North Korean deployment that pushed the Biden administration to allow Ukraine to use U.S.-provided weapons to strike targets further inside Russia – a policy made public this weekend.

A M142 HIMARS launches a rocket towards Bakhmut on May 18, 2023. (Photo by Serhii Mykhalchuk/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images)

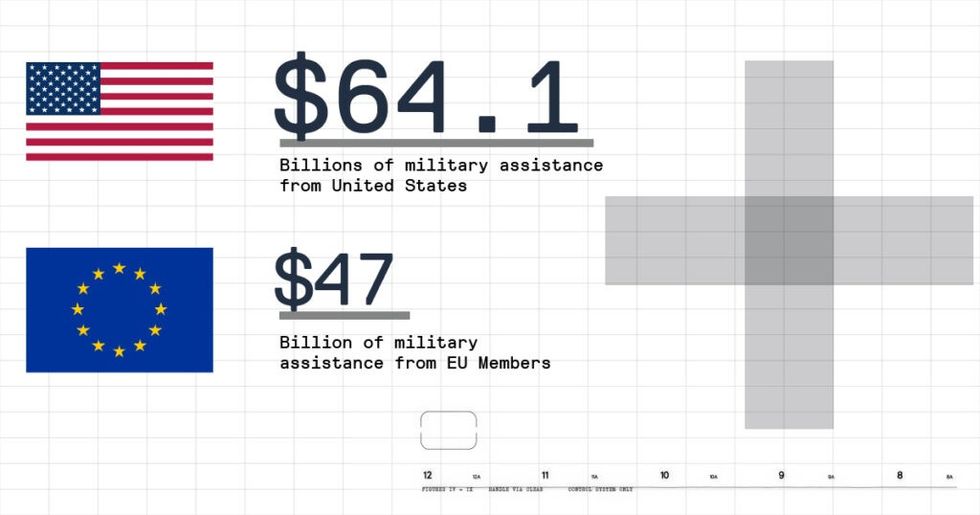

Billions in military aid

Since the early days of the war, Ukraine has relied on the U.S. and its other Western allies for military assistance to resist Russia’s invasion. The State Department reported on October 21, 2024 that the U.S. had provided more than $64.1 billion in military aid. In addition, European Union member nations have provided $47 billion in military assistance.

Highlights of the U.S. military aid:

- Three Patriot air defense batteries and munitions;

- 12 National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS) and munitions;

- More than 3,000 Stinger anti-aircraft missiles;

- More than 40 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) and ammunition;

- More than 200 155mm Howitzers and more than 3,000,000 155mm artillery rounds;

- More than 7,000 precision-guided 155mm artillery rounds;

- More than 70,000 155mm rounds of Remote Anti-Armor Mine (RAAM) Systems;

- 72 105mm Howitzers and more than 800,000 105mm artillery rounds;

- 31 Abrams tanks;

- 45 T-72B tanks;

- More than 300 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicles;

- 189 Stryker Armored Personnel Carriers;

- More than 900 M113 Armored Personnel Carriers;

- More than 400 M1117 Armored Security Vehicles;

- 20 Mi-17 helicopters;

- Switchblade, Phoenix Ghost, Puma Tactical Unmanned Aerial Systems.

The vessel TQ Samsun, a grain ship, off the Black Sea. on July 17, 2023 in Istanbul, Turkey. (Photo by Sercan Ozkurnazli/ dia images via Getty Images)

Ukraine's economy hit hard

Ukraine’s economy has been devastated by the combination of direct damage from Russian attacks, the human toll, and the drop in trade. First Deputy Prime Minister Yulia Svyrydenko told Reuters that Ukraine’s economy today is about 78 percent of its prewar size.

As of January 2024, the Kyiv School of Economics assessed direct war damages at $155 billion. The cost of long-term reconstruction and recovery has been estimated to be $486 billion.

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine exported more than 60 million tons of grain annually, accounting for roughly 10% of the global grain market. The war and Russia’s subsequent Black Sea naval blockade caused a drastic drop in exports. These have since largely recovered: for the 2023-2024 marketing year, Ukraine is projected to export 56 million tons of grain, back to 93% of pre-war levels. This rebound was achieved by a combination of overland transport to Europe, Ukraine’s new Black Sea maritime corridor, and the Ukrainian military’s remarkable success targeting Russia's Black Sea Fleet. Still, Ukrainian grain production is expected to fall short of pre-war levels due to issues such as fertilizer shortages, farmers’ abandonment of fields, and the laying of land mines. The U.S. Department of Agriculture forecasts Ukraine’s 2024–25 wheat output to be 23 million tons, down from 33 million tons before the invasion.

Russia's economy remains resilient

The Cipher Brief has reported that even though Russia has faced more than 2,000 sanctions in response to its invasion of Ukraine, its economy has demonstrated remarkable resilience. The reasons vary: continued energy revenues from oil and gas exports; strategic shifts to non-Western markets; and wartime industrial expansion. Some sanctions have had limited effect: sanctions on agriculture have been softened to avoid global food insecurity, and the export of Russian critical minerals and metals has continued, including via indirect channels to Europe. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects Russia’s economy to grow at a rate of 3.2 percent — the fastest of any advanced economy this year.

However, experts also note that Russia now has a wartime economy which may be unsustainable in the longer term. It is reliant on significant growth in defense-related industries, propped up by massive increases in government spending, and the economy is vulnerable to fluctuations in oil and gas prices.

Russian President Vladimir Putin gives an interview at the Kremlin in Moscow on March 12, 2024. (Photo by GAVRIIL GRIGOROV/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

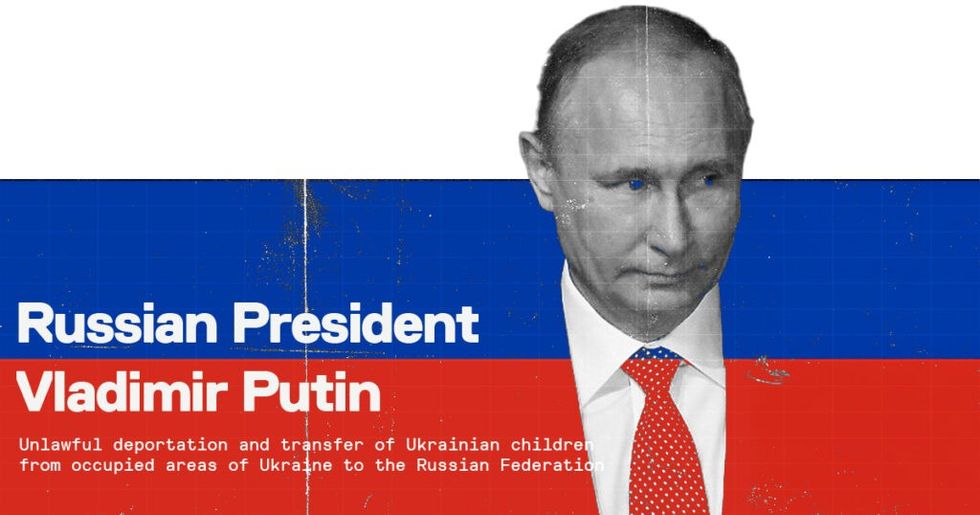

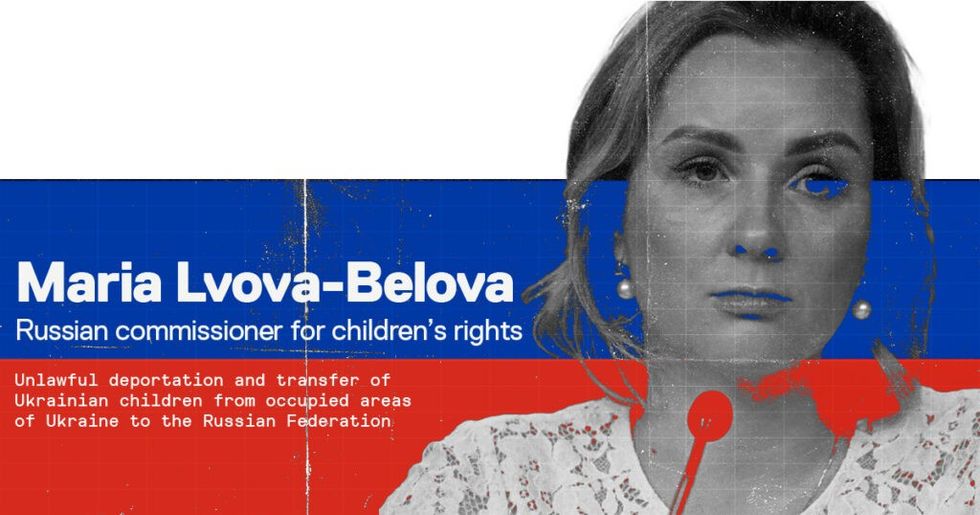

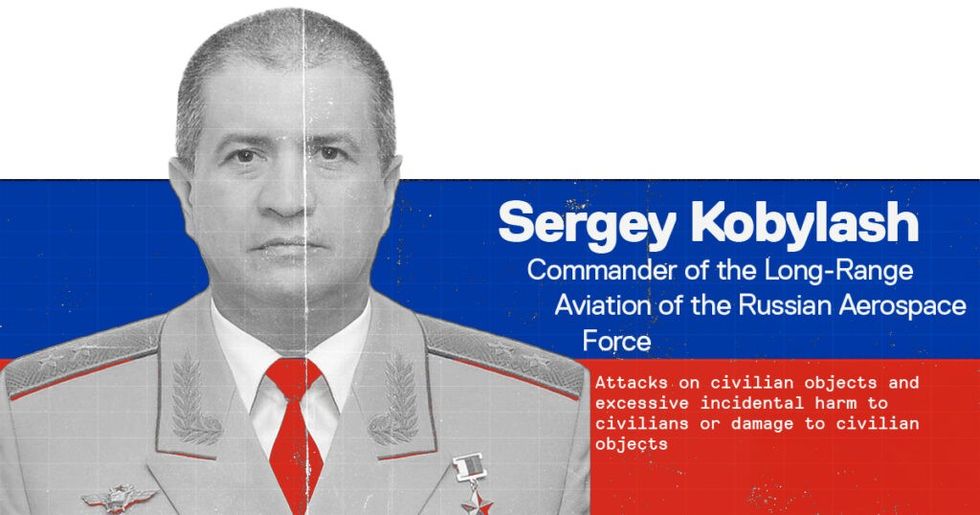

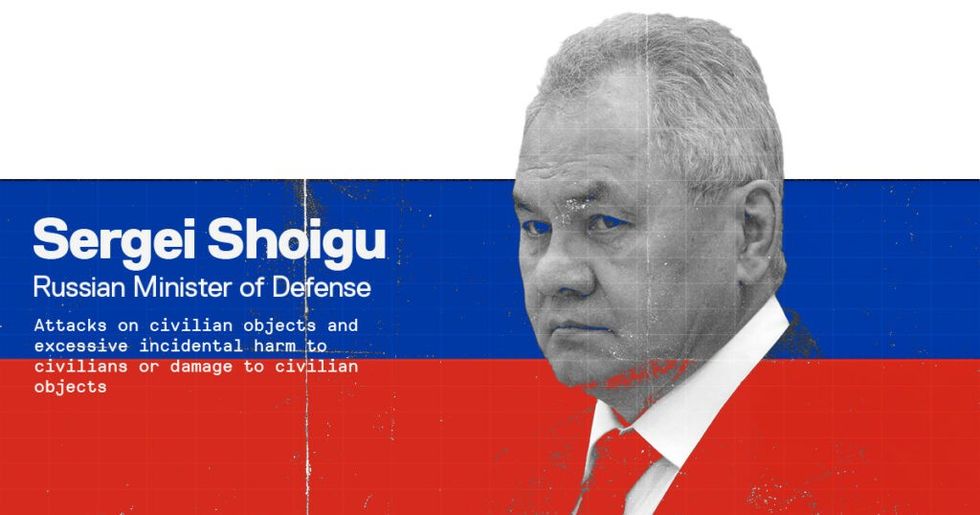

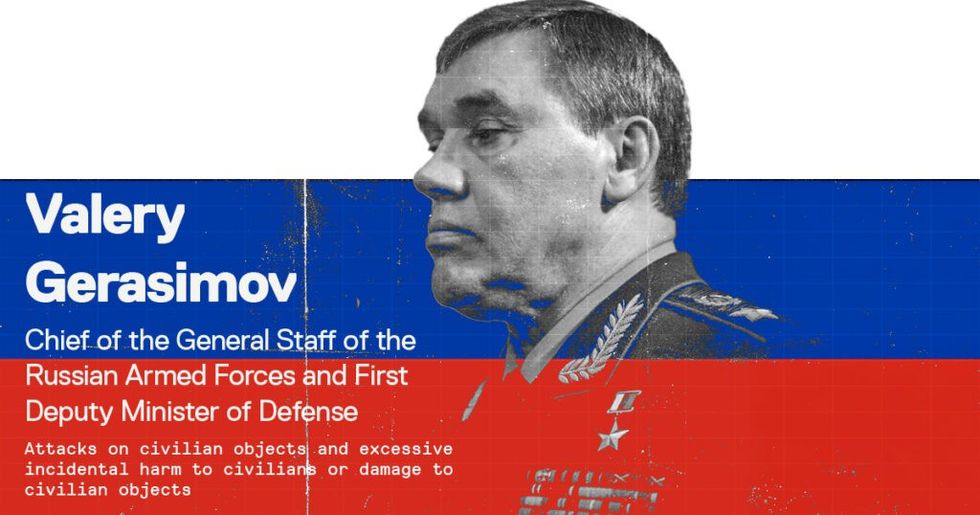

Russian leaders accused of war crimes

Since his “special military operation” began, Russian President Vladimir Putin and other senior Russian officials have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. In March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian commissioner for children’s rights, for the unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation. This marked an unprecedented moment: never before had a sitting leader of a major global power faced such charges from the ICC.

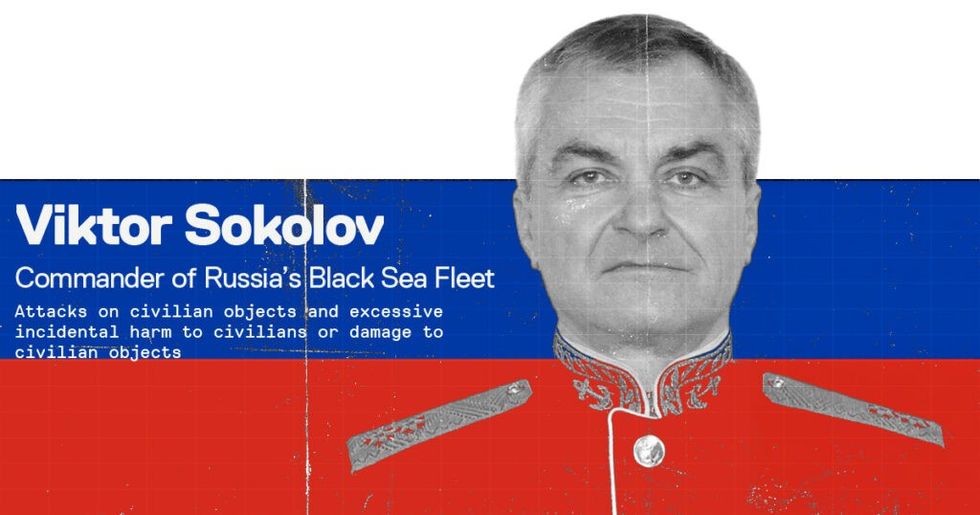

The ICC also issued arrest warrants for top Russian military officials — Viktor Sokolov, who was Commander of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet; Sergey Kobylash, Commander of the Long-Range Aviation of the Aerospace Force; Sergei Shoigu, who was then the Minister of Defense; and Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces and First Deputy Minister of Defense — for the “war crime of directing attacks at civilian objects” and “the war crime of causing excessive incidental harm to civilians or damage to civilian objects,” as well as “crime against humanity of inhumane acts” under article 7(1)(k) of the Rome Statute.

Design by Connor Curfman.

Ethan Masucol contributed reporting.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief.