The Middle East went through maelstrom developments during the Obama Administration. Some of these were put into motion by the 2003 American invasion of Iraq. Others, such as the Arab Spring, were the direct result of corrupt and brittle authoritarian regimes no longer capable of responding to their citizens’ aspirations and needs. Now, after eight years of Obama, it is difficult to argue that much has improved.

In fact, save for a spike in the price of oil, the region has suffered deeply from the after effects of the Arab Spring; economies were battered, tourism revenues collapsed, civil wars and foreign intervention created an image of interminable uncertainty. Only the Gulf region managed to wall itself off from these negative influences. After the oil price collapse, even the Gulf countries have had to tighten their belts and look for alternative business models.

Outside of the Arab Spring, the most dramatic development has to be the civil war in Syria and the simultaneous emergence of the Islamic State for Iraq and the Syria (ISIS). After six years of conflict, the Syrian regime has managed to survive but at tremendous cost. Hundreds of thousands have died, cities large and small have been reduced to rubble, and half of the population has been displaced, either at home or abroad. The political-military map has also changed significantly: the “moderate” and not-so moderate rebels are on the defensive after losing Aleppo to regime forces backed by Russian aviation and militias aligned with Iran. This change and Turkey’s about face to join erstwhile adversaries, Russia and Iran, in negotiating a cease-fire are the telltale signs of Russia’s return to the region as an important player.

Russia’s primary objective is to prevent the U.S. from engaging in regime change; it is not interested in constructing a new order. The Obama administration, while pursuing a strategy of replacing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, was more interested in limiting America’s role in the region by ending the Iraqi misadventure. This explains its cautious approach to the Syrian regime. Obama also sought to de-escalate the conflict with Iran by shepherding the nuclear deal in the hope that the Iranian regime would moderate itself or be transformed in the long run.

The emergence of ISIS, however, has upended Obama’s calculations. The rout of the Iraqi army and capture of Mosul by ISIS – followed by a triumphant declaration of its caliphate with Raqqa as its capital in 2014 – forced Obama to take ISIS on. By partnering with the PYD – a Syrian Kurdish group affiliated with the Turkish Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) – Obama gambled that he could deal ISIS a mortal blow in Syria by capturing Raqqa. He did not succeed before the end of his term.

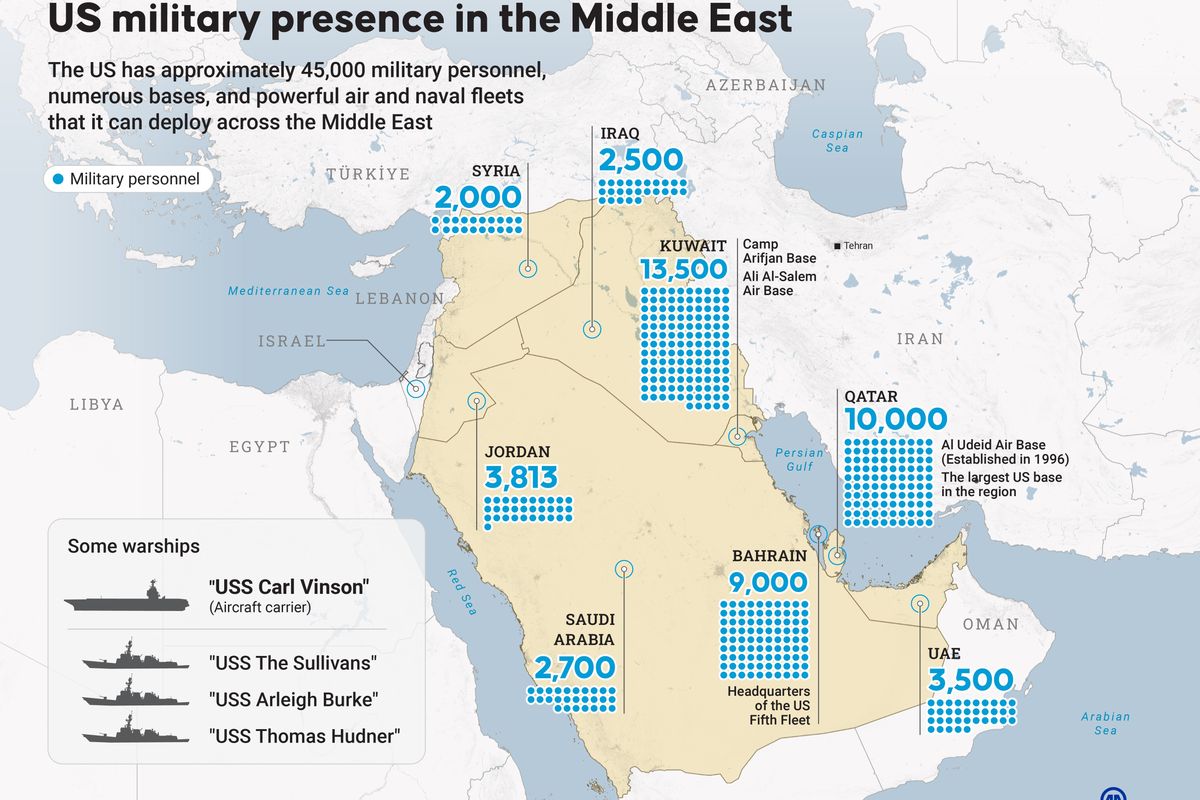

The Trump administration faces a series of challenges in the Middle East; they vary in intensity and priority. They can be divided along two categories: the semi-dormant ones, which can at any time reemerge to occupy the headlines. These include the Israeli-Palestinian, Israeli-Hezbollah fronts or regime stability in the likes of Egypt. The ones that are on the front burner are where the U.S. is involved in armed conflict: Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya, or Iran, where despite the nuclear agreement tensions are high. Of all these, Syria and Iraq should be the top priorities, because their fate will determine the future of the Middle East.

In Syria, the Trump administration faces its first test – and possibly opportunity – as it decides what to do with the ongoing Raqqa operation. Trump promised to eradicate “Islamic terrorism,” and therefore, continuing or perhaps even accelerating the Raqqa operation could give the new administration a much-needed early victory. This can only be achieved with the Syrian Kurds, a move that would further aggravate relations with Turkey and its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who views the PYD as the main threat to Turkey. Early signs point to an intensification of ground and air operations.

The second challenge is Iraq. Here Trump has made matters much worse for the U.S. by instituting a ban on Iraqis, and thereby, unnecessarily earning the ire of the Iraqi public and institutions, upon which the U.S. military depends to fight ISIS. Also, the administration should worry about countering ever-growing Iranian influence. In Iraq, the fight to reclaim Mosul from ISIS is only half completed. Even after Mosul and Raqqa are cleared from ISIS presence, the fact of the matter is that ISIS will continue to exist in the region, including in Iraq and Syria.

Hence, the administration will not only have to be vigilant, but also maintain relations with Arab governments to remain active against ISIS. This requires careful diplomacy and balancing many different equities. Unfortunately, the new administration may have squandered much good will early on.

Finally, the Trump administration will have to decide what posture to assume with respect to Russia in the region. Russia, of course, is bigger than just the Middle East. It is also involved in other theaters important to the U.S., including Ukraine and eastern Europe. In the Middle East, Moscow is in the driver’s seat with respect to the Syrian regime’s continuity. Whether Washington agrees with what Vladimir Putin has achieved in Syria and gives its consent, there still remains the issue of refugees in Turkey and elsewhere who need to be resettled, preferably in Syria. For that, the Russians have no answer or tools. The region will therefore look to the U.S., whether the White House likes it or not.