As Brexit-induced uncertainty continues to roil international markets, the U.S. Congress may soon deliver a second punch to the gut of the global economy. Congressional failure to ratify the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement this year would foreclose the only realistic option for meaningful global trade liberalization for years to come and would be interpreted as an unequivocal rejection of the long-standing presumption of U.S. economic leadership. This would reinforce perceptions – much to the delight of Moscow and Beijing – that post-WWII economic doctrine and its institutional pillars are crumbling. Although it may be difficult to infer from the nonchalance at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue, the stakes and implications are significant.

On its face, the TPP is a comprehensive trade and investment agreement between the United States and 11 other Pacific-Rim nations, which reduces tariffs and other impediments to trade, blazes new trails for tackling protectionism that lurks behind borders in discriminatory domestic regulations and policies, establishes rules for curbing the market-distorting practices of state-owned enterprises, sets good precedents for keeping international electronic commerce safe from protectionist impulses, and positions U.S. businesses, workers, consumers, and investors to benefits from the region’s growth.

The TPP’s value as an agreement to create greater wealth and higher living standards by more closely integrating 12 economies that account for 40 percent of global GDP is of primary importance, but there is also a bigger picture to consider. The TPP is the only vehicle that can plausibly fill the void created by the once successful, but now dysfunctional, multilateral negotiating “round” approach to global trade liberalization, which served the world well for a half century. As such, its fate will be seen by the next generation as an inflection point in the history of globalization, marking either the beginning of a period of global retrenchment, insularity, and economic friction or the resurgence of international cooperation, liberal institution building, and economic expansion.

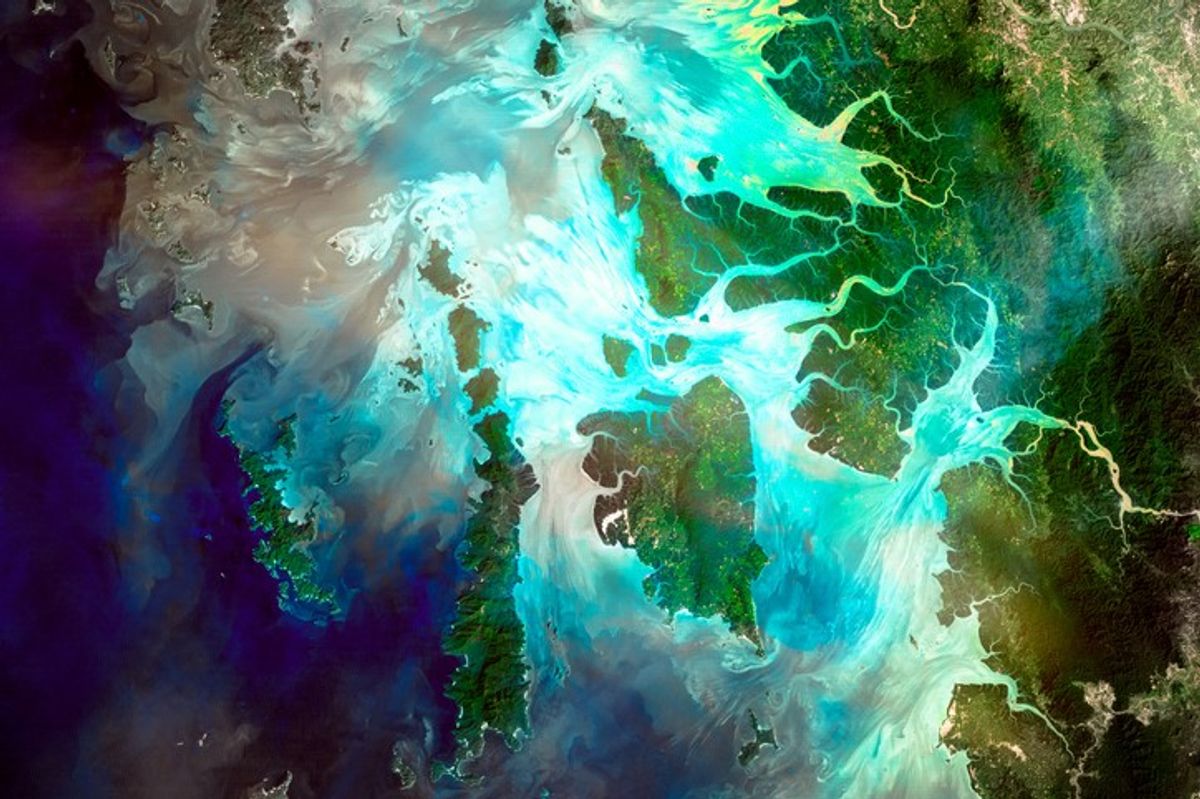

Unlike most other trade agreements, the TPP permits new members to join, if they meet the standards established and the conditions set by existing members. The fact that TPP has achieved critical mass allows its terms to be offered on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. Just as larger bodies floating in space have significant gravitational pull on smaller, surrounding objects, the TPP – by virtue of its heft – would pull countries in Asia, Latin America, Europe (yes, the United Kingdom), and eventually Africa and the EU into its orbit, because the costs of remaining an outsider will increase with each new accession.

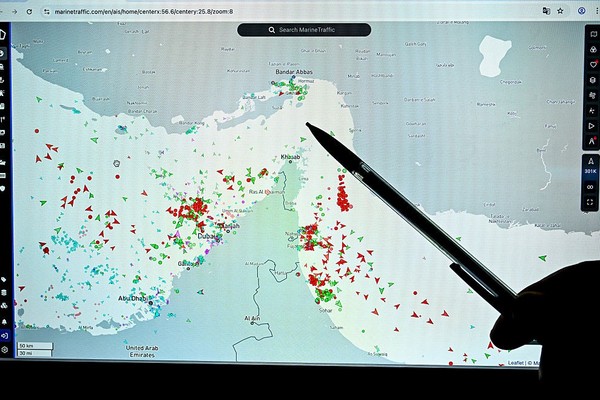

The evidence of this effect is considerable. Mindful of the costs of capital flight and investment diversion, as production platforms and supply chains shift from TPP outsiders to TPP members, current non-members such as South Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and Taiwan have been considering and implementing various domestic reforms to improve their prospects for eventually joining. And with TPP rules and benefits applying to China’s most important trade partners, Beijing will have no better alternatives than to embrace the TPP itself.

The TPP was borne of geo-political considerations in Hillary Clinton’s State Department as the economic component of the Obama administration’s “strategic pivot” to Asia. There could hardly be a better implement in the U.S. geo-economic policy toolbox than the TPP for projecting U.S. values, securing U.S. interests, and compelling China and others to play by the rules that will govern international commerce in the 21st century.

Yet Congress can’t see past election-year politics to acknowledge the TPP as this multifunctional tool that will increase the size of markets, elicit compliance with U.S.-authored rules of international trade, and resuscitate U.S.-led multilateral liberalization. Or perhaps Congress hasn’t sufficiently contemplated a world after it rejects TPP.

In that world, China is the large mass drawing smaller countries into its gravitational pull. With China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership negotiations waiting in the wings for the TPP’s failure, regional countries will be drawn more deeply into China’s orbit. Although that doesn’t mean trade between the United States and those countries will suddenly dry up, it does mean that existing China-focused investment and supply chain relationships will be reinforced, new ones will emerge and become established, and the costs of reorienting those relationships in the event of some future TPP implementation will increase with each passing year.

Those countries would be less inclined to continue engaging in unilateral domestic reforms to qualify for the TPP without the payoff of TPP membership as motivation, which would retard their own development and encourage compliance with rules and standards preferred by China. U.S. commercial and diplomatic interests in the region would be further impaired by Washington’s failure to follow through on its promises. Foreign governments that incurred political costs to push the TPP in their countries with expectations of U.S. participation wouldn’t soon forget that the United States proved to be an unreliable partner. Hopes for the TPP jumpstarting a new wave of global trade liberalization would be dashed and, with U.S. credibility diminished around the world, America’s policy objectives would become more difficult or, in some cases, impossible to meet.

By foregoing immediate and future economic benefits, weakening Western institutions, and handing the baton to China, the geopolitical and geoeconomic costs of failing to ratify the TPP would be enormous.