SPECIAL REPORT — Given how unpredictable 2024 proved to be – did anyone foresee the fall of Bashar Al-Assad, the decapitation of Hezbollah, an invasion of Russia or the deployment of North Korean troops to Europe? – it might seem a fool’s errand to imagine what the next 12 months will bring. And in this look at the year ahead, we hedge a bit; rather than a list of concrete predictions, we offer a list of questions, and feel safe in saying that the answers will go a long way to determining what 2025 will look like, on the global security landscape.

Before we get started, we want to take this opportunity to wish you a happy and healthy 2025, in which all your more hopeful predictions come true.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the U.S. Capitol on July 10, 2024 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Anna Rose Layden/Getty Images)

Will peace come to Ukraine? And if so, what will it look like?

It may be the most complex and consequential question for the year ahead. Donald Trump has pledged repeatedly to end the war in Ukraine, saying he’d do so “in 24 hours.” Since Trump’s election, his promise has driven activity on multiple fronts, all aimed at gaining leverage before any potential negotiations: Russia has intensified its strikes across Ukraine; Ukraine has stepped up attacks on Russian territory and courted Trump and his aides; and the Biden administration, in its final days, has been rushing what may be a last major tranche of funds and weapons to Kyiv.

What might a Trump peace plan look like? On the one hand, the president-elect’s team includes harsh critics of U.S. aid to Ukraine – vice president-elect J.D. Vance and Donald Trump, Jr. are in this group – and Trump himself has shown a disdain for NATO and a relatively warm approach to Russian President Vladimir Putin. All of which might suggest a deal that gives Russia the land it has taken since the 2022 invasion (about 18% of Ukrainian territory) and a lifting of U.S. sanctions in exchange for a halt to the war.

But there are others in Trump‘s orbit – including Marco Rubio and Mike Waltz, his nominees for secretary of state and national security advisor, respectively – who are more hawkish vis-à-vis Russia. And in any case Trump, who styles himself as the consummate dealmaker, may not wish to be seen as weak in a negotiation with Putin. The Atlantic Council’s Matthew Kroenig said last week that “Trump will walk away from a bad deal.”

Waltz and Kroenig co-authored a November piece in the Economist that hints at a possible Trump approach. They argued that the Biden Administration’s support for Ukraine “in a war of attrition against a larger power is a recipe for failure,” and called for increased U.S. natural gas exports and a crackdown on Russia’s illicit oil sales “to bring Mr. Putin to the table.” If the Russian leader refuses to talk, they said the U.S. should provide more weapons to Ukraine with fewer restrictions on their use. “Faced with this pressure, Mr. Putin will probably take the opportunity to wind the conflict down.”

A man to watch in all this is retired Lieutenant General Keith Kellogg, Trump’s choice for special envoy to Ukraine and Russia. In June, Kellogg co-authored a memo along similar lines: increased support for Ukraine if Putin refused to negotiate, but also a halt to U.S. aid if Zelensky rejected talks with Moscow. Kellogg will visit Ukraine later this month, and the new administration's approach may include talking to Putin – something the U.S. and most of its NATO allies have refused to do since Russia's 2022 invasion. But Kellogg was also sharply critical of the Kremlin after a December 25 barrage of Russian missile strikes against Ukraine.

“Christmas should be a time of peace, yet Ukraine was brutally attacked on Christmas Day,” Kellogg wrote on X. “Launching large-scale missile and drone attacks on the day of the Lord’s birth is wrong."

For his part, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky expressed hope in his New Year’s address that the Trump administration would “compel Russia into a just peace.” For Zelensky and many Ukrainians, “just” would mean effective security guarantees, and the return not only of that 18 percent of lost territory but Crimea as well. The latter is almost certainly a pipe dream, for 2025 and perhaps years to come.

People walk past a poster of Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and slain Palestinian Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran on August 10, 2024. (Photo by ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images)

In a weakened Iran, a new nuclear deal – or a rush to a bomb?

Axios dropped a dramatic story Thursday, reporting that White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan had recently presented President Biden with options for a U.S. attack on Iran's nuclear facilities, if the regime in Tehran began taking final steps towards obtaining a nuclear weapon. Axios said the plans weren’t the result of fresh intelligence, but a case of what one official called "prudent scenario planning" in the event that Iran enriched uranium to 90% purity – a key precursor to a nuclear weapon.

It’s a startling shift for an administration that came to office eager to negotiate a new nuclear deal with Iran, after Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the landmark 2015 agreement. It also reflects two of 2024’s most dramatic developments in the region – both involving Tehran.

The first is a dramatic erosion of influence. Iran’s military proxies Hamas and Hezbollah have been battered by Israel; its chief ally in the region, Syria's Assad, is gone; and Iran’s own military abilities have been called into question after a series of Israeli strikes.

The second involves Iran's progress towards the bomb. When Trump pulled out of the nuclear deal, he predicted Iran would come groveling back to the negotiating table in the wake of a “maximum pressure“ campaign against Tehran. That never happened. Instead, Iran has increased its enrichment of uranium to 60% purity, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and would need only a few days to make the last leap to the 90% mark.

On the one hand, Iran’s nuclear program has never been so close to producing a bomb; on the other, elements of the program have never been as vulnerable to attack. A late October series of Israeli strikes knocked out air defenses protecting several of Iran’s nuclear sites.

Iran would still need to develop a delivery system – but the bomb itself has been a red line for the U.S. and Israel. And so the questions for 2025 are stark: Will a weakened and cornered Iran rush through those final stages to acquire a nuclear weapon, despite the likelihood of a robust Israeli – and perhaps American – military response? National security advisor Jake Sullivan warned of exactly that last week, telling CNN that given Iran’s myriad problems, “It’s no wonder there are voices (in Iran) saying, ‘Hey, maybe we need to go for a nuclear weapon right now.’”

Cipher Brief expert Nick Thompson, a former CIA Paramilitary Case Officer, echoed the point. “With Iran down and their axis of resistance shattered across multiple fronts,” Thompson said, “the regime may feel that enriching uranium to 90% and weaponizing it is in their best interest.”

For Iran, the alternative route would be utterly different, and represent a paradigm shift: facing its new geopolitical troubles, the regime might seek a new deal with the West that preserves its power, but dramatically scales back its nuclear capability.

For the U.S. and its allies, the new realities create policy questions, and the Trump approach is unclear. His interest in dealmaking is always present, and the new Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian has floated the idea of negotiations; but the President-elect has also spoken of exerting even more pressure on Iran – as have many of his senior aides. That could mean more sanctions, or a preemptive strike against Iran's nuclear program.

In a special “Memo to the President” for The Cipher Brief, Beth Sanner, a former Deputy Director for National Intelligence at ODNI and daily briefer to the President during the first Trump term, argued for a carrot-and-stick approach.

“Iran’s significantly weakened state means greater leverage…the U.S. [must] leverage its partners in order to increase pressure,” Sanner wrote. That pressure, and the threat of military action, “must also include an off-ramp and the promise of benefits to Iran. Iranian leaders will need to have confidence that halting the country’s nuclear program and curbing its regional malign influence will bring benefits, including sanctions relief."

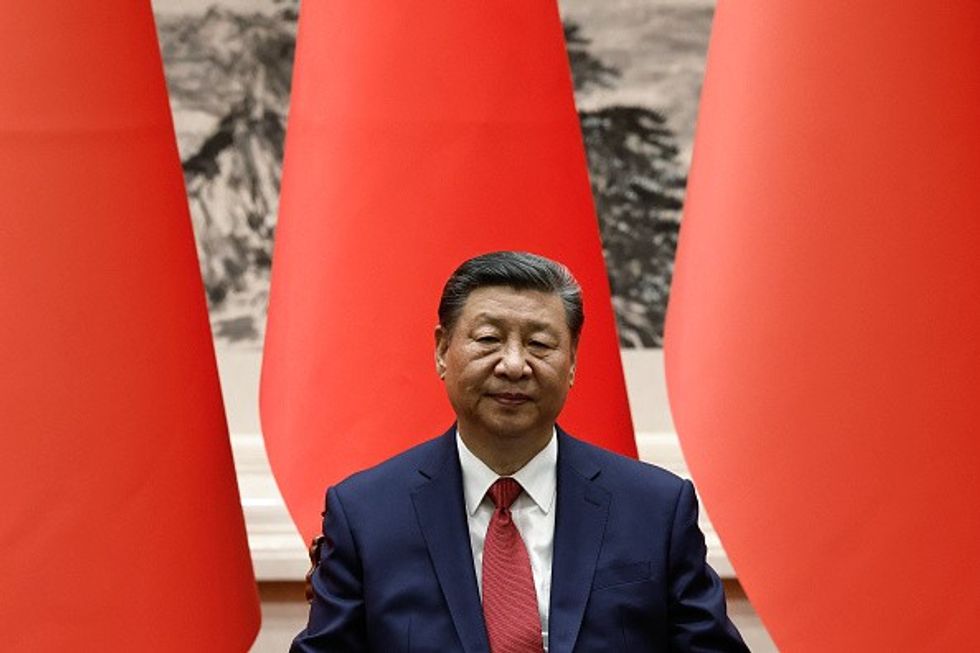

Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People on May 31, 2024 in Beijing, China. (Photo by Tingshu Wang - Pool/Getty Images)

For the U.S. and China, how bad will things get?

The second Trump administration will inherit a very different relationship with China than the one that existed eight years ago. Common ground between Washington and Beijing has all but vanished; a trade war looms; and small issues (see the 2023 balloon incident) threaten to morph quickly into crises.

A huge question for 2025, then: can future U.S.-China crises be averted?

“I think it’s more severe, more complex, even if not as militarized, as the original Cold War,” Michael Collins, Acting Chair of the National Intelligence Council, said at the 2024 Cipher Brief Threat Conference. “China is learning on any given day to compete with us in an increasing array of arteries, to challenge us and contest us, to undermine us without actually going to war, taking advantage of new techniques, new devices, and even proxies around the globe to do so.”

Overall U.S.-China tensions will rise and fall depending on several factors: whether China continues its cyber offensive against U.S. infrastructure (more on that below); whether Trump follows through on his pledge to levy 60% tariffs on imports from China (a pledge he’s made as often as his promises of peace for Ukraine and Gaza); and if frustrations rise in Beijing, how – and whether – Xi lashes out in response.

Other flashpoints are likely to involve Chinese activities in Southeast Asia. And while Xi’s plans for Taiwan get most of the attention, it may be that a crisis over the South China Sea is the one that lands in 2025. In the past year, China and the Philippines had several dangerous run-ins in those waters – in particular around the Second Thomas Shoal, where a clash in June resulted in the wounding of a Filipino sailor. Neither Beijing nor a newly strident Manila – under the leadership of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. – have shown signs of backing down, and the U.S. is bound by treaty to assist the Philippines. If China resorts to a heavier hand in the South China Sea, say in the Sabina Shoal, which lies just 90 miles from Philippine territory, would the U.S. come to the Philippines’ aid?

As for Taiwan, Xi said in his New Year’s address that “no one can stop the historical trend of national reunification” with Taiwan. Here, too, the other side has a strident leader in newly minted Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te. For his part, Lai said last week that he would spend 2025 strengthening Taiwan’s defenses, and he specifically cited the dangers posed by China, Russia and North Korea to the “international order.”

Which takes us to the next question.

Russia's President Vladimir Putin and China's President Xi Jinping attend an official welcoming ceremony in front of the Great Hall of the People in Tiananmen Square in Beijing on May 16, 2024. (Photo by Sergei BOBYLYOV / POOL / AFP)

What will the “Axis of Authoritarians” do next?

A few years ago, this question wouldn’t have made much sense. What “Axis” is that? Now the term has become a common name for the coalition that includes China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea – a group that doesn’t operate in an ideological straight line, but shares an interest in transactional collaborations and general antipathy toward the West.

The “Axis” had a productive 2024: various deals helped Russia and Iran get around western sanctions; Iranian drones pummeled Ukraine and are now being manufactured in Russia; Russian military and technological aid benefited North Korea; and North Korean troops deployed to Russia's war against Ukraine – a stunning insertion of forces from the other side of the world into a European conflict. It’s a long and troubling list, and it begs a question: what will the Axis of Authoritarians do next? And can it be deterred?

Various Cipher Brief experts have said the key for the U.S. is to bolster its own alliances (some of which President-elect Trump has questioned) and to explore creative diplomacy to drive a wedge between these countries. That could mean a Trump diplomatic effort with Beijing or North Korea – (Cipher Brief expert Amb. Joseph DeTrani has advocated for both); or the aforementioned push for a deal with Iran on the nuclear program.

Another Cipher Brief expert, former CIA acting director John McLaughlin, sees another possibility: if the war really does end in Ukraine, it might take the wind out of the Axis’ sails.

“I think the most important issue for the year is whether there will be a settlement of the Ukraine war,” McLaughlin told us. “If a formula can be found that gives Ukraine security and neutralizes Russia’s aggression, it would take much of the steam out of the so-called ‘Axis of Authoritarians’ and potentially diminish the threatening aspect of these four countries collaborating so closely.”

And that leads to the next question.

North Korea's leader Kim Jong Un during his meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Vostochny Cosmodrome in Russia's Amur region on September 13, 2023. (Photo by VLADIMIR SMIRNOV/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

In North Korea, Trump and Kim together again? Or a new war?

During his first term, Donald Trump famously held the only U.S. presidential summits with Kim Jong Un, and became the first sitting American president to set foot on North Korean soil when he stepped over the demarcation line at the North-South demilitarized zone. Those summits produced great drama but few results, and former officials and analysts are divided as to whether they should be tried again.

Many say that the North must show evidence of a new direction before winning the reward of any White House recognition – halting those troop deployments to Russia, for example, and at least pausing its ballistic missile and nuclear testing. Others, including Ambassador Joseph DeTrani, a former CIA Director of East Asia Operations who was a Special Envoy to the Six-party talks on North Korea, believes a dramatic American gesture could be the wedge that wrests Pyongyang from the Russians, if not the entire “Axis of Authoritarians.”

Without high-level American engagement, Amb. DeTrani argues, North Korea will continue to support others in the “Axis,” and perhaps move closer to a new conflict with South Korea.

“We should not give up on North Korea,” DeTrani said. “It’s likely North Korea will respond favorably to an overture that proposes the eventual lifting of sanctions, on an action-for-action basis, as North Korea halts the production of fissile material for nuclear weapons and halts all nuclear tests and ballistic missile launches.”

A fighter jet being prepared ahead of the Israeli army's attack on Iran, on October 26, 2024 in Israel. (Photo by Israel Defense Forces/Anadolu via Getty Images)

What next for Israel’s wars?

2024 ended with a fragile truce in Lebanon, some thin hopes for a cease-fire and hostage deal in Gaza, and new Israeli attacks against the Houthi militia in Yemen. All three conflicts involve proxy militias tied to Iran; and hanging over them all is the possibility of a larger-scale war between Israel and Iran.

Might 2025 change any of that?

Outsiders will likely play a role in determining the answer; to take one obvious example, if the regime in Iran chooses the above-referenced less confrontational approach. Meanwhile, President-elect Trump has promised to end the Gaza war, though with even fewer specifics than he has offered for the war in Ukraine. (Last month Trump said there would be “all hell to pay” for Hamas if it didn’t free the hostages). Trump and many of his top foreign policy advisors have talked about a smaller U.S. military footprint overseas – which in this region could mean the drawdown of American forces in Syria and Iraq and/or a pullback of the major U.S. naval deployment in the Middle East. Such measures could weaken Israel’s position, particularly vis-a-vis Iran.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his war cabinet may feel they have momentum as 2025 begins, given their military successes against Hamas and especially the battering of Hezbollah's leadership and military arsenal. They also believe they have a friend in Trump; Netanyahu and the extreme right wingers in his cabinet were jubilant after the November election, figuring the next American president would give Israel an even freer hand than it’s already had against its adversaries.

But as with other geopolitical hot zones, Trump’s penchant for dealmaking may have an impact here. And some have suggested that his relatively good relationship with Netanyahu will make it easier for him to push for concessions from the Israeli leader.

At our 2024 Threat Conference, CIA Director William Burns urged the parties to any Gaza negotiations to understand that “it’s not just about brackets in texts or creative formulas when you’re trying to negotiate a hostage and ceasefire deal. It’s about leaders who ultimately have to recognize that enough is enough, that perfect is rarely on the menu, especially in the Middle East. And then you’ve got to make some hard choices and some compromises in the interests of a longer-term strategic stability.”

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Director Jen Easterly testifies before a House Homeland Security Subcommittee, at the Rayburn House Office Building on April 28, 2022 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

What cyber attacks will come next?

In 2024, Americans became more familiar with “Volt Typhoon," a China-linked hacking campaign that targeted U.S. critical infrastructure for espionage and information gathering. The attacks came as a shock – an infiltration of American infrastructure for the apparent purpose of gaining a cyber foothold, making it possible to inflict major damage in any future U.S.-China conflict.

“This is a world where a war in Asia could see very real impacts to the lives of Americans across our nation, with attacks against pipelines, against water facilities, against transportation nodes, against communications, all to induce societal panic,” Jen Easterly, Director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), told The Cipher Brief.

Then came “Salt Typhoon,” an attack that breached top U.S. telecommunications firms for more than a year before U.S. cybersecurity had any clue what was happening. Cybersecurity officials said they only learned of the infiltration more than a year after it was launched, thanks to an alert issued by Microsoft.

Once again, the attacks were traced to China, though in this case, the hackers weren’t just building a cyber beachhead; investigators said they had infiltrated U.S. telecommunications networks to access sensitive communications of top U.S. officials.

The National Security Agency Director and Cybercom head General Timothy Haugh put it bluntly: When it comes to cyberwarfare, “the PRC [People’s Republic of China] is not yet deterred.”

Easterly, the CISA Director, said of the China-linked attacks, “We think what we’ve seen to date is really just the tip of the iceberg.” And indeed, in the last days of 2024, the U.S. Treasury Department announced that state-sponsored hackers from China had breached the department entity that deals with economic sanctions.

Where's the rest of that "iceberg"? The nature of cybercrime makes it difficult to guess where it might strike next. One thing many of our experts agree on: the U.S. should get “much more aggressive” in its approach to the problem, as George Barnes, a former Deputy Director of the National Security Agency, told us last week. “This is unfortunate, and it should be a wake-up call.”

Supporters welcome Ahmed al-Sharaa, the leader of Syria's Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group that headed a lightning rebel offensive against the regime of Bashar Al-Assad, before his address at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus on December 8, 2024. (Photo by AREF TAMMAWI/AFP via Getty Images)

In Syria, can moderates win the day?

This last question would have looked strange just two months ago: “Moderates,” winning in Syria? But it’s now a fundamental issue facing this crucial Mideast nation, in the wake of the stunning rebellion that ended the 53-year dictatorship of the Assad family in Syria. Will the rebel coalition, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), stick to its promise of inclusive government, and drop its past jihadist principles? And can it unify the country?

It’s been only a month since the HTS rebels drove Bashar Al-Assad into exile, and many Cipher Brief experts are cautiously optimistic, based on what they’ve seen thus far: a plan to unite rebel factions under one government; a union of various armed fighters who would serve in a new national army; and an absence of bloodshed or widespread acts of vengeance in the days since the rebellion. Last week a top U.S. diplomat met the HTS leader, Ahmed Al-Sharaa, and said he “came across as pragmatic.”

We shouldn’t expect “Jeffersonian democracy,” as Cipher Brief expert Ambassador Gary Grappo put it, but “there’s an opportunity to move Syria into the collective of moderate Arab states, not necessarily a democracy but one that fosters stability at home and in the region.”

That’s the hope.

Meanwhile, the pessimists have a long list of worries.

For one thing, many of Al-Sharaa’s rebel forces were drawn from jihadist groups – raising questions about their future loyalties. And even if HTS means what it says, there remains the question of whether it can effect a peaceful transition. Dozens of smaller militias are scattered across the country, most notably a Kurdish group that controls much of northeastern Syria, and the Islamic State (IS) extremist group, which still operates in parts of central Syria. HTS’ best efforts may still lead to civil strife, and that could draw in Syria’s neighbors – Turkey and Iran in particular. In perhaps the worst-case scenario, the power vacuum in Syria may lead to a new haven for terrorists – IS or others.

Two weeks ago, speaking at the Council on Foreign Relations, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the danger lies in the possibility that Syria veers towards something more like what’s happened in Afghanistan since the Taliban retook control in 2021. “There is a lesson there,“ Blinken said. “The Taliban projected a more moderate force face – or at least tried to – in taking over Afghanistan, and then its true colors came out.”

Ethan Masucol contributed reporting.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief.