The Academic Incubator program works with colleges and Universities across the country on highlighting the next generation of national security leaders. If your program is interested in joining the Academic Incubator, which provides free Cipher Brief memberships for enrolled students and faculty, shoot us an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com

The author of this Academic Incubator piece, Alexander Naumov, is a double B.A. candidate at George Mason University's Schar School of Policy and Government studying International Politics and Russian & Eurasian Studies, graduating in December 2020. He is also a frequent event writer at the Michael V. Hayden Center for Intelligence, Security and International Policy. In May 2019, he was the sole US invitee to Russia's 'Volunteers of Victory' summit in Moscow and Tula, Russia.

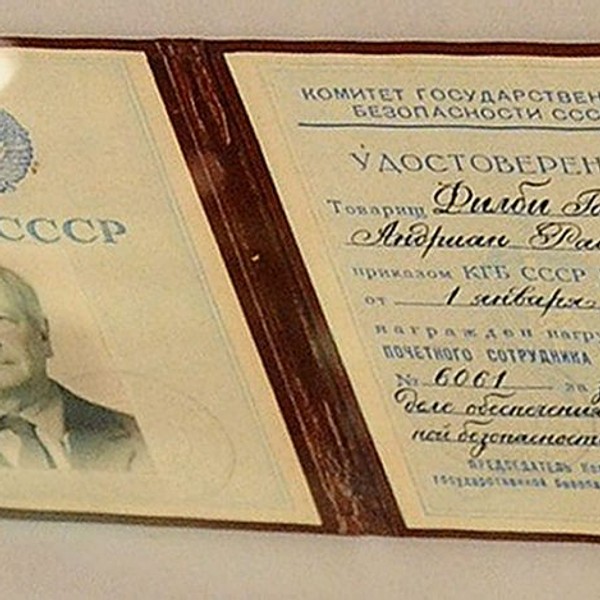

Last May, the 2010 Russian Illegals case returned to the public eye. The case, which the FBI called “Operation Ghost Stories” concluded in June 2010 with the arrest of ten Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) officers on non-official cover in Virginia, New York and New Jersey, just as Russian President Dmitry Medvedev concluded his state visit to Washington, DC. One of those ten SVR officers who were traded back for four Russian nationals, Elena Vavilova, released a fictionalized version of her autobiography titled The Woman Who Can Keep Secrets last year. It is an emotional story from the other side of the Vienna airport spy exchange that inspired six seasons of ‘The Americans’ and supplements Gordon Corera’s newly released book on the same case.

Analysts in the United States should not overlook Vavilova’s book for three reasons. First, it offers a glimpse into the modern Russian intelligence community culture: the reasons that people join, what values motivate its officers, and what myths Russia holds about its revered intelligence professionals and their American adversaries. Second, the protagonist’s observations of the West expose Russian perceptions and biases, highlighting logical leaps from world events to perceived threats. Third, it describes open-source and ‘gossip’ intelligence-gathering, showing that it should not be underestimated when social media and electronic surveillance gets the most attention.

Vavilova speaks through Vera Sviblova, her fictional alter ego and protagonist. As in real life, she goes from being talent-spotted by the KGB as an undergraduate student in Tomsk State University to being arrested for espionage in northern Virginia. At her career’s start, the reader will already dive into Russia’s intelligence community culture. Sviblova is ecstatic that “an interesting life was opening up ahead along with, judging by the movie ‘Seventeen Moments of Spring,’ the brave profession of an intelligence officer filled with feats and accomplishments.”

Her cinematic reference is a 1973 miniseries depicting Soviet illegal Maxim Isaev, aka SS officer Max Stierlitz, thwarting the Third Reich’s negotiations for a separate peace with Allen Dulles. Stierlitz embodies self-sacrifice and quiet professionalism and is as ubiquitous in Russian culture as James Bond is in the West.

The mythological role model of Isaev is a window into Russian intelligence culture today. Sviblova/Vavilova shows that an officer candidate’s path is heavily influenced by the historic national catastrophe of Operation Barbarossa. Similar to how countless U.S. public servants identify September 11th as the decisive factor in serving their country, for Russians like Vavilova, this ‘never again’ moment is the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War with Germany on June 22, 1941. When Sviblova joined the KGB in the 1980s, she recalls this moment of grave danger to her country’s existence as her raison d’etre.

As she continued spying decades later, the memory of World War II in Russia’s consciousness – which, unlike for America, was a borderline apocalyptic event - becomes hazier but no less present in daily life, as in reality. During a stressful nap on the edge of surveillance in 1980s Vancouver, Sviblova sees wars, mountains of bodies, and mushroom clouds. Suddenly, she realizes that “she has the ability to prevent these catastrophes, but for this she must do something important…” The book is more than tinged with Soviet and nostalgic ideology, but the concern with national existence is paramount.

Vavilova’s narrative also helps reveal worldviews and biases of her generation of Russian intelligence. In a critical moment in the book, Sviblova takes credit for warning Moscow of NATO’s first air campaign against Bosnian Serbs in 1995 through building a relationship with Robert Green, a fictional US representative to NATO. She also listened to chatty French air force pilots in her cover-job photography studio.

Several Russia scholars like Fiona Hill and Angela Stent noted the fall of the Berlin Wall as a formative moment for the late KGB generation of then-Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Putin, captured in the quote that “Moscow was silent.” For Sviblova’s generation, it is Russia’s response to Operation Deliberate Force.

Weeks after NATO bombs hit their targets, the illegals learn that President Boris Yeltsin defied the Russian parliament’s proposal to condemn the operation. Sviblova describes this lack of action as the hardest moment of her life, one that even a secret medal, “For Courage,” failed to ease.

This perception – that an inactive foreign policy means Russia’s doom - is best captured during the couple’s final deployment to Washington. In the book, they mostly act as listening posts, collecting sensitive information like a fishing net for things that should have not been said. For instance, at a golf game with Green, now a high-level DIA officer, Sviblova’s husband eavesdrops on Ukrainian exchange officers playing beside them. Despite the cosmopolitan life the pair enjoys in America, their children’s home, the evidence they gather only serves to confirm their preconceptions: that the United States overthrows regimes with no local autonomy, is in bed with the Russian domestic opposition, and dream of returning their country back to its Great Depression of the 1990s.

Additionally, Vavilova has a message that may even touch her America counterparts: that to succeed in intelligence requires one to “truly love your motherland, hold yourself together… And, of course, keep secrets.” And despite the pro-Kremlin narratives of malicious American policy, the mission closest to the illegals’ hearts is a familiar: to prevent, at all costs, a date in history. For the United States, it is September 11th. For Russia, it is June 22nd.

Finally, Vavilova’s fictionalized autobiography also highlights the importance of open intelligence, or OSINT, and human intelligence (HUMINT) today. American scholars have noted Russian illegals’ tendency to collect mostly open-source information. Vavilova’s story does almost nothing to alter this image. However, her open-source HUMINT moments, like with the Ukrainian officers, should give pause to talkative Western staffers with security clearances. It should warn possible targets in the United States – in government, all ranks of the military, and on college campuses – that traditional operational security is as important in 2020 as cyber hygiene. The United States intelligence community should not lose any focus on classical operations for the sake of today’s cyber and digital influence threats.

There are three takeaways for American national security analysts from this “other side” perspective. First, it is a lesson in Russian intelligence community culture, which is important given its lionization in society. Russian President Vladimir Putin is a product of this culture and his leadership of the country is set to be extended into the 2030s. Second, equipped with better understanding of the Russian mindset, U.S. and NATO diplomatic efforts can do a better job of assuring Moscow that a June 22, 1941 scenario is not on the table. I have personally witnessed how the history of the Second World War can be a bridge despite genuine disagreements, and this type of understanding might help lower tensions. Finally, Vavilova’s story demonstrates Washington should never look at OSINT and HUMINT officers as products of a bygone era rendered obsolete by technical means of collection: the Russians certainly don’t.

The Cipher Brief’s Academic Partnership Program was created to highlight the work and thought leadership of the next generation of national security leaders. If your school is interested in participating, send an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com.

Read more national security perspectives and insights in The Cipher Brief and sign up for our free daily newsletter.