At least 97 people were killed and hundreds more injured across the Oromia and Amhara regions of Ethiopia over the weekend, when Ethiopian security forces fired at peaceful protestors, reports Amnesty International.

Both protest movements stem from land issues and economic, political, and ethnic tensions.

Members of the Oromo – Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group – began protesting last November over a plan to expand the boundaries of the country’s capital Addis Ababa, allocating farmland for development.

Demonstrators from Amhara – Ethiopia’s second largest ethnic group – started protesting last month over a 25-year-old land dispute: Protestors say the Welkait district was illegally incorporated into the northern Tigray region when the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) came to power in 1991. They want the land reintegrated into Amhara.

The EPRDF is dominated by Tigrayans, who make up about six percent of the population, whereas the Oromo and Amhara make up about 61 percent of the population.

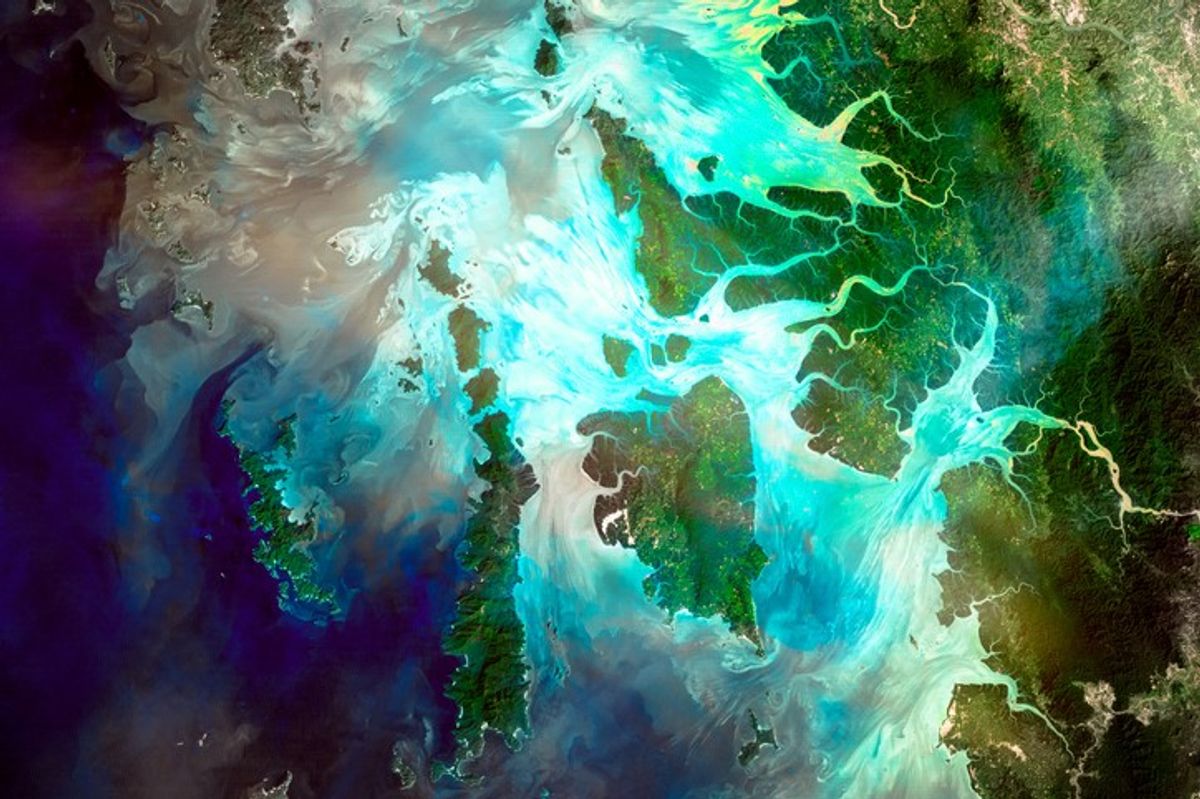

These internal issues are being exacerbated by climate change. In 2015 and during the first half of this year, the landlocked East African nation experienced its worst drought in decades, due to an unusually intense El Niño effect. Meanwhile, certain areas already affected by drought experienced abnormally heavy rains in April, May, and June, causing flash floods and landslides.

“These events are a natural part of the global climate system,” says Ashebir Wondimu, a senior forest expert in Ethiopia’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. “However, climate change affects the intensity and frequency of these natural events,” he explains.

The extreme intensity this year has led to internal displacement, famine, disease, and the loss of livelihoods for many who depend on an agreeable and predictable climate for their incomes. USAID Ethiopia’s Senior Development Outreach and Communications Officer, David Kahrmann, notes, “Upwards of 80 percent of Ethiopian livelihoods are tied to rain-fed agriculture or pastoralism.”

Wondimu tells The Cipher Brief that “migration of people from place to place in search of food and additional aid” will pose a challenge to national security.

Ethiopia is already home to the largest refugee population in Africa – nearly 738,000 (as of May 2016) from Eritrea, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, and elsewhere – reports the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Now, UNICEF raises the concern that possible internal migration due to the drought could “trigger tensions between various ethnic groups in some regions, as it recently has between Oromo and Somali ethnic groups.”

UNICEF predicts around 150,000 people will be displaced due to drought, flooding, or conflict.

Meanwhile, UNICEF reports approximately six million children are at risk from hunger, disease, and lack of water in Ethiopia due to the drought, and around 10.2 million people are in need of food aid.

Antoinette Sayeh, Director of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Africa Department, recently said at an event in Washington she expects severe economic impacts of the El Niño related drought to really play out this year.

Right now, Ethiopia is receiving about $6 million for climate-related assistance from the World Bank. With the drought, Ethiopia needs at least $10 million or more, says former World Bank Managing Director and COO Sri Mulyani Indrawati, who was recently reappointed Minister of Finance for Indonesia.

Although the security implications of this year’s strong El Niño effect seem difficult to manage, the Ethiopian government (together with international partners) is doing relatively well in predicting and responding to extreme climatic events.

They have learned from past droughts, famine, and political turmoil, says Kahrmann. “Today, the ruling EPRDF coalition is acutely aware of the political risk of a failed drought response.”

Ethiopia’s strategy is two-fold, explains Wondimu: adaptation and mitigation. “In the short-term, the government is responding by providing emergency support to those affected […] In the long-term, the government is working on various programs [including] reforestation, restoration, and integrating natural resource management activities,” he says.

Ethiopia is also getting a lot of help from the United States. The U.S. is the largest humanitarian donor to Ethiopia, says Kahrmann, providing more than $706 million is assistance since October 2014. Thanks to its Famine Early Warning Systems Network, USAID was able to detect early warnings of this latest El Niño and launch “an aggressive, multi-faceted response in Ethiopia,” Kahrmann explains.

Ethiopia is not the only African country to be hit with the heightened intensity of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events. Much of southern Africa is feeling the pain as well. Mozambique and Malawi are experiencing the worst drought in the region in more than three decades.

It’s pretty much a given that climate change and the ensuing intensity of normal climatic occurrences will continue. This is a major national security concern – as Ethiopia’s drought shows. Adequate government planning and response is key to managing climate change’s risks.

Kaitlin Lavinder is a reporter at The Cipher Brief.