Data from NASA shows this July is the hottest on record. Gavin Schmidt – Director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which is responsible for temperature measures – tells The Cipher Brief’s Kaitlin Lavinder that this is part of a long-term warming trend, and the implications for U.S. national security include infrastructure loss and mass global migration.

The Cipher Brief: NASA just released data showing this July has been the hottest month on record. Can you go over the main points of that data and explain how you collect that information?

Gavin Schmidt: The data is from national weather services and ship records from around the world – all public domain information. It’s collated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and then we take that information and analyze it to create an estimate of how different a place is compared to its normal temperature values – the anomalies. So every month the data comes in, and we calculate how much the anomaly is for each month. We’ve been checking the warming of the globe as a function of time since 1981.

We are currently in a global warming period. Since around October last year, we’ve been breaking records – month in and month out – partly as a function of the El Niño event that was ongoing in the Pacific and has now somewhat faded. That has a large-scale, slightly lag effect on the global mean temperatures. We’ve had El Niño events before, of course, but the reason why this is causing so many records to break is that the underlying trends – the baseline – have shifted slightly up so we’re seeing warm fluctuations on top of an ever-rising trend.

TCB: What are the implications in terms of future temperatures?

GS: The El Niño event is fading so we don’t expect quite as many records to be broken in the coming monthly numbers. But the fact of the matter is, we’re seeing the same long-term trend. From one El Niño to the next, it’s warming; from one La Niña to the next, it’s warming; from one neutral year to the next, it’s warming. Those long-term trends are driven predominately by the increase in greenhouse gases, and that’s driven predominately by the increase in carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation. Since that is not stopping – in fact, it’s increasing – we anticipate the long-term trends are going to continue to rise.

On top of that, we’re going to have a one year warm, one-year cold type of oscillation, but on top of a rising temperature trend. The long-term trends are going to be such that we are going to see these records broken every time an El Niño, for example, strikes.

TCB: Can you give a few examples of areas in the world where temperatures were the highest this past July?

GS: The temperatures were highest in the Tropics, so there were a lot of places in the Tropics where they were seeing record-breaking numbers of more than 123°F. There was potentially a record for the whole of Asia – with about two weeks of temperatures around 129°F. Those kinds of things are interesting for the record books. But one day, one place, one record is not the impact. The impact is in the whole shift of the distribution of weather states toward warmer conditions. Everyone can stay at home for a day, but how can you go work in a field or at a construction site if it’s more than 120°F for two weeks?

TCB: What are some of the national security concerns of rising global temperatures for the United States?

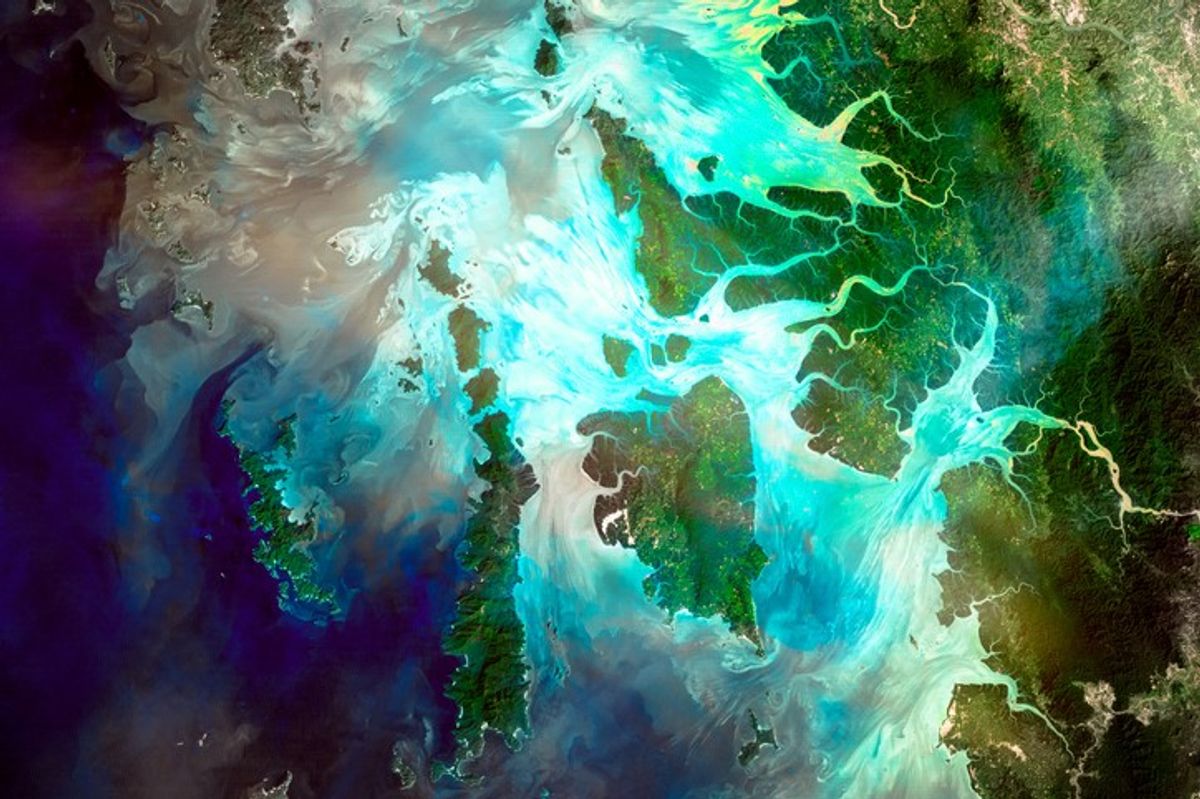

GS: I’m not a national security expert, but something like extreme rainfall causing flooding—like we’re seeing in Louisiana—is a big concern. The National Guard has to come out for situations like that. Coastal flooding when you have storm surges combined with the rise in sea level and infrastructure that is perhaps not in the most sensible place (like right along the coast) – those are things we have to be aware of.

The national security implications obviously go beyond just what is happening locally and go into, for example, the consequences of harvest loss in Vietnam or Thailand, which changes the rice market which causes riots in Egypt. Those are the kinds of climate affects that push the complicated system we have in ways that could be very serious.

TCB: What does this all mean in a very broad context? Although this past July was the hottest month on record, the earth has certainly been warmer during periods in the past – before homo sapiens were around.

GS: The earth is not going to become uninhabitable. But our society has a huge investment in the climate the way it is: where we grow our crops, how we build our homes, how close we build our homes to the coasts or to the rivers, what we build our homes with, how we power ourselves, how we get around. If you think about it, all of these things depend on the climate we have. That means we have – in society – an enormous vested interest.

Trillions and trillions of dollars have been invested in the expectation that the climate is going to stay the same. When the climate refuses to cooperate and when we’re pushing it in a direction that is now very clear, we’re putting at risk all of that infrastructure and all of that accumulated information. Because with the decisions we’re making now, you can’t bet on the fact that the climate is going to remain the same. You can’t use the same building codes. You can’t use the same zoning. You can’t put stuff as close to the sea as you used to be able to. You can’t build Manhattan where it is because of the danger of what might happen.

In Manhattan or Miami Beach, for example, there’s a huge amount of infrastructure that is right at sea level, and there’s already flooding on a pretty regular basis. That’s not sustainable, and the flooding is going to get worse. What’s going to happen to that infrastructure? A lot of people are going to start building barrages like they did in Venice. But eventually that stuff is going to fall into the sea – and that’s hundreds of millions of dollars in investment.

And that is just one example. Now expand that out to naval bases around the world, to Shanghai, to Calcutta – now you’re talking about 100 million people who live within one meter of sea level. Where are those people going to go? The issue is not that 100 million people are going to die. The issue is that 100 million people are going to have to move, and that is going to cause all sorts of dislocations and problems.