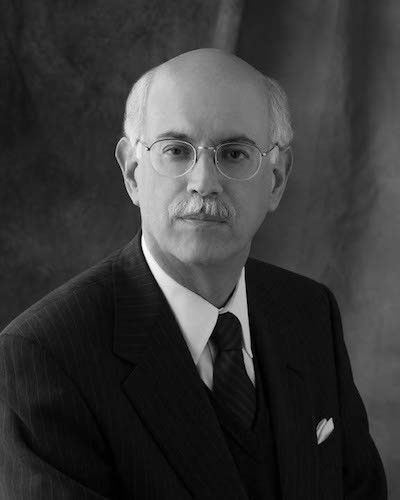

President Trump's proposed budget looks to slash almost $26 billion from diplomacy and foreign aid programs next year. Those in favor of such a move argue that U.S. foreign aid and economic development spending is an inefficient and wasteful use of taxpayer money. However, in June, 16 retired generals and admirals testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee that international economic development assistance "is not charity - it is an essential, modern tool of U.S. national security." The Cipher Brief’s Fritz Lodge spoke with former Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Andrew Natsios about the value of foreign economic development, what role it has played in U.S. foreign policy, and the dangers of walking it back.

The Cipher Brief: In your mind, how does international economic development affect U.S. national security and what policies has the U.S. historically pursued to promote that development?

Andrew Natsios: People don’t know this, but the economic miracles in South Korea and Taiwan were orchestrated by U.S. AID [Agency for International Development] in what was actually quite an intrusive way. This wasn’t just healthcare and roads and schools, this was 30 economists running the South Korean economy with the intent of developing an export-led economy. Apparently, the mission director of AID in South Korea would actually go into meetings with President Park Chung Hee and tell him what to do.

In the old AID, the organization was a very powerful force in the developing world. At times, the AID mission directors of some countries were more powerful than U.S. ambassadors or military commanders, because they were actually trying to build institutions in a way that would be sustainable if there was a communist insurgency. So this was directly connected to our foreign policy, as it still is now. This is not just a humanitarian agency that does nice things – it does do nice things and I am proud of that, but it also does these things because we cannot afford to have our allies fail in critical areas of the world.

TCB: How has that role evolved in more recent years?

Natsios: Oddly enough, the closer that AID has come to the State Department, the less it has played this stronger more independent role that we saw in the early years. I wrote an essay studying the development over the last three or four decades of the inspector general’s office within AID, the general accounting office that does investigations and audits, the Office of Management and Budgets (OMB), and other regulatory arms of the U.S. government that try to control the federal bureaucracy – there’s a professor at Georgetown who calls this the “counter-bureaucracy” – and this counter-bureaucracy has had a very bad effect on innovation. AID officers are very worried about having their careers ruined by a bad audit, the auditors end up competing with each other to find purported infractions, and the resulting risk aversion that we now see across the federal government due to the creation of this counter-bureaucracy is enormous.

This culture also requires that everything be codified. If we had to codify on a quarterly basis every year the effect of economic reforms on South Korea, they would never have happened. We did not know that the Korean and Taiwanese economic models were going to be such spectacular successes until 15 years into the program. Even then it wasn’t clear, there was still a debate amongst economists. Now, of course, it’s regarded as genius, but it wasn’t at the time.

So, one of the major problems that we face is what I call the time lag effect. You do the program but the improvement doesn’t really register until after the program is over. We did a 20 year worldwide retrospective analysis of all of AID’s democracy and governance programs, which were basically created by Ronald Reagan in 1985, so we studied from 1985 to 2005. There were billions of dollars spent in 80 countries around the world and we compared the results to the Freedom House democracy and governance indicators. In the end, the scholars who did the study showed that there was no improvement for 12 or 14 years, at which point the programs ended and then there was a couple of years’ delay before, all of a sudden, the numbers started increasing each year substantially.

Here’s another example, AID between 1951 and 1971 built 12 institutes of technology in India with the Indian government. Once built, we took these institutes and linked them with 12 U.S. engineering schools. This program ran for 20 years, and I read the audit at the end of 20 years, which said that these schools were mediocre at best and that this was not a great success story. However, years after that, these emerged into some of the finest engineering schools in the region because it takes a while for institutions like these to mature.

These programs do work but (1) they take a long time to work and (2) they are not very visible. Politicians like things that are quick and have measurable results but the problem with that is a lot of these things are extremely hard to measure.

To answer the question, economic development does work but it does not work over night. It cannot be measured in the immediate present when the program is being run. It takes time for the institutions to develop and mature. But once they do, the consequences are quite profound.

TCB: What’s a better way to rate effectiveness then? How can we know when this is working?

Natsios: You can rate effectiveness over a longer time horizon. I can give you an example right now of something I did in 2003. Ethiopia was one of the poorest countries in Africa. Very low economic growth, famines every two years, and it had a very high birth rate – an average of six children per family. There was a famine scare in 2003 and I said enough is enough. I went to see the prime minister and said “your country is becoming poorer not richer and someone’s going to ask the question, what have you been doing all these years?” – he had been prime minister for about ten years at this point. We had a seven-hour conversation and I went through ten economic reforms that could begin to turn things around, and at the end of it, he agreed to five of the ten reforms. These included property ownership reforms, and particularly family planning reforms, which helped produce a 35 percent drop in fertility. When we began the program, five percent of Ethiopian women were using birth control, when we finished 55 percent were using it. In addition, we did a huge health program and an agricultural program to increase agricultural productivity. All of that has resulted in double digit annual growth rates. AID had a lot to do with that, and we also managed to coordinate international donors – the World Bank, European governments, etc. – to cooperate on these reforms.

TCB: What are the realpolitick advantages of a success story like that to U.S. foreign policy?

Natsios: Ethiopia is the second largest country in Africa, it is situated in a strategically critical area where Africa meets the Middle East, it is culturally very pro-American and more. It is important that a long term strategic ally of the United States prospers, and that basic rationale spread to countries across the world. Our strategic interests are directly involved in these countries; this is not an abstract idea.

TCB: What have you seen so far in the Trump Administration? How does the policy stance differ?

Natsios: The proposed foreign aid cuts are crazy, and even worse is the proposed merger of U.S. AID into the State Department, which would be disastrous for aid programs. I have spoken very publicly condemning these cuts.

However, on Monday this week, the Senate Appropriations Committee, chaired by Lindsay Graham, passed a spending bill, which reversed almost all of these cuts and put restrictions on [Secretary of State Rex] Tillerson’s reforms to State. This wasn’t even a close vote in committee, and it was a real message to the administration to not screw around with these foreign aid and diplomatic budgets anymore.

This is interesting because, historically, the Democrats like foreign aid but they like it for social programs, they are not so interested in the trade, economic development, and even democracy promotion aspects. The Republicans tend to lean the other way, but it’s usually the Republican president that drags along the Republicans in Congress. This time, for the first time since the foreign aid program was established, it has been the Republican president undermining foreign aid programs, and the Republican Congress saved the program. That is a profound shift.

TCB: What about the effect of perception? Clearly, the administration has shown little interest in these kinds of programs, how does that stance affect U.S. foreign policy?

Natsios: It’s a very bad message, but General James Mattis has publicly defended foreign aid programs, and McMaster has expressed similar views. So I think that the foreign policy team, which the president has now put in place is pro-foreign aid, pro-development, and pro-humanitarian assistance. That ultimately may be what’s most important.

TCB: If that’s the case, what advice would you give to that team to restore some confidence in these programs?

Natsios: We need to look at the next budget. If they make these kinds of cuts again, then I will have been wrong. If they leave the accounts alone, then that will also send a message.

I also do think that we need to make changes to these programs. I love the health programs, but we are spending a third of the entire aid budget on health. The reality is, these countries are never going to develop unless they also grow economically. You can’t support these social programs unless there is economic growth to produce tax revenue so the countries can take the programs over themselves. Growth is critically important to the development of these societies.

If I had any advice to the administration it would be to, first, increase the economic growth funds. If you want to encourage sustainable growth in a country, you have to run sustainable programs that run over 10, 20, 30 year periods, like we did in South Korea, Taiwan, Ethiopia, Chile, Costa Rica, you name it.

Second, they need to invest in long term democracy and governance programs. All democratic institutions have to based and rooted in the culture of the local society, so this is not imposed, but democracy programs in a broad sense do work if you give them 10, 20, 30 years to mature. We should be spending a lot more money in critical countries of the world to stabilize and mature them so that they become stable allies of the United States.