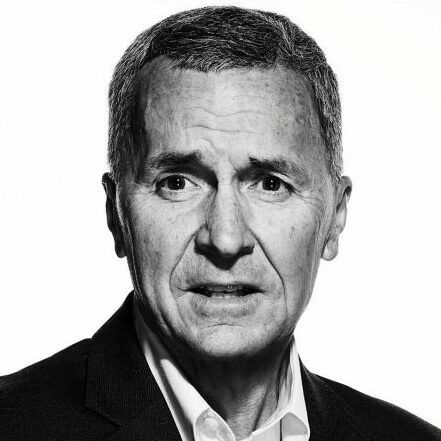

The Cipher Brief sat down with Rob Richer, the CIA's former Associate Deputy Director for Operations, to talk about the evolution of espionage and the value of human intelligence.

TCB: Does Hoffman’s book, the Tolkachev story, bring you back to the good old days of the Cold War?

RR: First of all, I never worked in Russia before I was a Russia watcher. I was a Middle East hand—that’s where I did all of my service. I was our Chief in Oman and I got a phone call to come back to Washington in the summer of 1995.

When I found out I was going to be targeting Soviets or Russians, I had never really worked Russia. I had run into them in diplomatic circuits and during our operations. And the reason they wanted me was because they were bringing in someone who had never worked that target from outside what was the Soviet East European division, because we knew there were other moles. We knew we had problems in the building which proved out. We knew there were problems in other U.S. government agencies. So I was brought back to run Russian external operations and then run what’s called “Russia House,” which is internal and external operations.

TCB: Hoffman spends a great deal of time talking about the “deadly dance” between the US and the Soviets on the streets of Moscow. I take it that sort of game of espionage is still alive and well today?

RR: I can’t speak to today because I’m no longer current. I can speak to the late 90’s and into the 2000’s and, yes, the game is under play. Based on what I understand, it’s probably actually more aggressive today because under Putin, who was kind of a failed SVR officer, he does see us as a major enemy. He also has a little man’s complex, which is that he wants to take us on. He doesn’t want us known as the only superpower. And every time he hears that, he reacts badly.

But if you look at what he’s doing, what’s in the public eye, he’s using the spy services for economic gain for himself and for the people around him.

TCB: One of the big takeaways of the Tolkachev case is that it speaks to the enduring value of human intelligence. Do you think today’s spy game has been too enamored with technology?

RR: I think the War on Terror has made technology at the forefront of our efforts. Technology allows us to have an immediate reaction. It allows us to immediately know where someone is. It can show us what they’re doing at the time we get the information.

Here’s what it can’t tell us: intention. Technology can’t tell us long-range focus. That’s what a human spy does. A human spy sitting in the JCS version of China can tell you, “Our long term planning is for eventually taking Taiwan by 2020.” I’m just throwing that out like it’s happening by 2020. There’s no other way you’re going to get that. They’re not going to put that on a system that we can hack. You need to know that. You need to know, “Hey, two weeks ago we decided on the Politburo level to devalue the yuan,” the Chinese currency. We knew the impact that would have on the United States, and look at what happened to the stock market today. Now, that’s from a number of factors, but that was one of the impacts.

Look at the hacking; the Chinese are behind a good portion of the hacking taking part in the United States. That’s not ad hoc. That is government sanctioned, from semi-private enterprises. We need to know that. We have to have a human spy tell us that. Technology can trace this back to a cover company, which eventually we may trace back to a PLA entity, but that doesn’t give us much. What really gives us this, is a guy in the Politburo saying, “We had a session in the group of five and decided that we would undermine DoD, or compromise their secrets, or steal their technology, by these efforts.” That helps a lot more because if you look at some of the comments coming from the President of the United States in the last couple days about China, we say we believe. We don’t say with certainty. A human spy gives you certainty.

If you look at what a human spy did in this book—and granted we’re talking in the late 70’s until ’85—this is a man who provided documents and stuff that I don’t even think today we could steal. We could take a picture of a RADAR dome, we might intercept some signals about what it can and can’t do, but Tolkachev came in and said, “Here is what we are thinking about designing. Here’s a prototype we’re working on.” He saved our government billions of dollars of research and defensive measures. That’s a human spy, and you can’t get that from technology all the time.

If you look at what happened on 9/11, we knew something was afoot that year or six months before. There was a meeting in June of 2001 where (CIA officer) Cofer Black and his team went in and briefed the White House. They said, “We know something’s afoot and we know there’s airplanes involved, we just don’t know where, but we know it’s imminent.” Remember, we didn’t have a whole lot of information. The White House didn’t have enough information to act on it. Every technology in the world was trying to collect and we couldn’t get it. A human spy—someone close to Khalid Sheik Mohammad (the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks)—could have given us that information. The hardest thing in the world to do—and people don’t understand this—is to recruit a human spy.

In the Tolkachev case, he was throwing letters at agency officer cars, trying to volunteer. The declared Chief of Station, Gus Hathaway, who was a legend as a counterintelligence professional, didn’t take him seriously. We worried he was a dangle because, at that time, we weren’t recruiting actively and handling inside. We would recruit outside, train them, and put them back in country, and they would never see a face. This was unusual.

TCB: For today’s generation of case officers who are going through training or just newly on the job, what do you think they should take from this book or this case?

RR: What they should take away is that personal relationships are as important as all your technical expertise. We’re spending so much time in war zones. A good portion of the workforce is rotating through Iraq, Jordan, and supporting war zones. They’re looking at Syria, they’re working in Iran, they’re going into Afghanistan, and that’s a good portion of where our skills are going. And in almost all those cases, you’re in denied areas where you do have some human operations, but you’re mostly embedded. You’re working with the military and using technology.

The problem is that I think we’ve undervalued the guy sitting in Vienna who meets someone from the Iranian Atomic Energy Commission and could do the song and dance for a year. A Russian or a Soviet in the old days would work an American for multiple tours. They would keep a Soviet in a particular country if that American looked vulnerable, and if the Soviet’s time was up, they’d keep him there, or they’d post him maybe at the next place this guy showed up.

We don’t think that way. Our view is: two-year tour, recruit someone, move on to your next assignment. I get promoted by recruitment. So I am going to go onto a development that looks even better and maybe there’s an easier target.

From what I understand, the Agency is pushing for more value recruitment, but it’s a skill that atrophied because of 14 years of warfare. So think about this: here you are, a case officer who has done multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, where you’re carrying an M4 pistol, a vest, and someone says, “I want you to wear a suit and tie and work undercover somewhere to work this target.” And you’re going, “Oh my gosh, adrenaline, adrenaline. You want me to sit and have cocktails with someone?”

I think what is an improvement in the process—and I saw it in my last four years, which was when we were fusing so much on the military, and when the analytical service was getting more integrated with the DO – this idea that it’s a team effort.

So I think the fusion of how we’re doing operations is much better. Forward deploying different types of people to stations on critical missions is more important.

TCB: Tolkachev stands out in a lot of ways because he was the perfect asset—in terms of what he was driven by, his ideology, the fact that he was committed, he had access—so in a lot of ways he was the dream recruit.

RR: And he had thought this through before he took the act. Think about that. Think about this guy’s personal gumption, personal courage. He tries the first time, leaves a note, which someone could have found, and nothing happens. He doesn’t know who picked that note up because he had to get out of the scene once he left it. He came back again. He did it again. Think about that. This whole time he was being looked at as a double agent, as a possible dangle.

TCB: I had read that he lived literally right next door to the U.S. Embassy.

RR: Which means that every other building around the U.S. Embassy was a spy haven watching us. Half the apartments were rented by the SVR who were photographing anyone who went in and out of there.

TCB: Living among the enemy.

RR: Exactly. Which may have actually helped protect him.