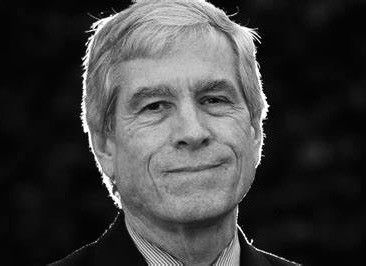

Warner served as Ambassador to Iran from 1993 to 1997, headed Australian Secret Intelligence Service and the Office of National Intelligence from 2009 to 2020, and negotiated the release of Australian hostages from detention in Iran in 2019 and 2020.

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE — Shiraz in Shiraz. Years ago, I was in Shiraz in the south of Iran having dinner and celebrating Nowruz, the Persian new year, with a small group of friends. The ancient symbols of Nowruz were all around us - a mirror, a plate of sprouting grass, coins, coloured eggs, a live goldfish - and a meal of delicious Persian food, together with homemade Shiraz wine made by my friends from their own Shiraz grapes.

“Down with the U.S.A”. The ten-story high mural in Tehran is iconic, striking and powerful in its simplicity: bombs falling out of the American flag onto Iran, “Down with the U.S.A” - a bumper sticker of the revolution - painted across the red and white stripes.

For generations Iran has been divided, torn and fought over between those who crave an interweaving of the old Persia and modernity, and those wedded to religious fundamentalism - which from the start of the revolution 43 years ago, quickly morphed into a fear and loathing of America (“the great Satan”) and the West.

When you live in and travel around this beautiful country you are confronted every day with these deep chasms and contradictions: the stunning mosques, morning and evening calls to prayer, and the morality police on the one hand; and the deep love for pre-Islamic Persia, together with a yearning for Western culture, on the other.

The young, bright, sometimes Western educated young men and women speak English with only the slightest accent. The women with their hijabs - head scarves - pushed as far back as possible. Parties - chadori-clad women coming through the door of my house in Tehran only to fling off their all-covering robes to reveal the shortest of little black cocktail dresses, the latest American music, European fashions, and alcohol. And it’s not just the young: grizzled bazaaris, diplomats, and some of the political elite also have links, affection and a history with the West (and sometimes a bank account). The connections with the West are old and close - so many Iranians live in Los Angeles, you often hear it called Tehrangeles.

Then there is the other Iran: deeply religious and conservative - seeing Western culture as an acid eating into the fabric of religious totalitarianism. Which it is. Many Iranian women choose to wear a hijab or chador, and not only in rural areas. To many, it is an important symbol of their faith and their culture. There is a deep religious conservatism in Iran.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the years in Tehran and Baghdad talking to some of the protectors of the regime and exporters of its revolution - from the Ministry of Intelligence and Security, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its key wings - the Qods Force and the Intelligence Organisation - and to senior mullahs in the religious centres of Qom and Mashhad. Many were bright, well-read, articulate and polished. Some were brutish, and some I found incomprehensible: there was no common ground for a meaningful exchange - our world views were so very different. But all were determined to protect and fight for the Islamic Republic.

The battle playing out in the towns and cities of Iran over the past two months has pitted these two alienated elements of Iranian society against each other.

The images have been stark. Courageous young women burning their hijabs - a symbol of religious persecution - standing bareheaded, confronting the security forces: “Women, Life, Freedom”; “Death to the dictator”.

This uprising has been different to earlier ones - student protests in 1999, widespread demonstrations in 2009 following Presidential elections, and a rolling series of protests in 2017 and 2019, against the government’s economic policies (GDP dropped by almost 60% between 2017 and 2020, and about 40% of Iranians live under the poverty line). This time, it has been more sustained and broader based - initially made up of girls and young women, but joined by Iranians of all ages and backgrounds, cosmopolitan Tehranis, oil workers, Baluchis in the east, and Kurds in the west.

Get your 10-minute national security daily brief with Suzanne Kelly and Brad Christian by listening to The Cipher Brief’s Open Source Report Podcast wherever you listen to podcasts.

It has also been about a much sharper rejection of the Islamic Republic, in all its aspects, small and big. Listen to some of the lyrics of the haunting unofficial anthem of the demonstrators in the song Baraye about what is fueling the protests:

“For dancing in the streets … For our fear when kissing …

For my sister, your sister, for of our sister … For the renewal of the rusted minds …

For yearning for just a normal life …

For the dumpster diving boy and his dreams … For this dictatorial economy …

For the massacre of the innocent dogs … For all these unstoppable tears …

For this compulsory heaven … For women, life, freedom … For freedom …

For freedom … For freedom.”

And ironically today’s unrest also has echoes of the revolution that overthrew the Shah in 1979, and brought the Islamic Republic into being. In the 1920s and 1930s, Reza Shah Pahlavi began a process to try and modernise his deeply religious and traditional country, including banning the hijab. His son continued his father’s modernisation work, but with mixed results.

In his brilliant analysis of the revolution, Days of God, James Buchan wrote that, “A phoney modernity confronted a phoney religious tradition in a fight to the death”. Iranians thought that the Shah and his Western allies “were destroying a civilisation they held dear".

Initially, the aim of the demonstrators was for a constitutional monarchy and a democratic transformation. But in the end, the revolution was stolen by the mullahs. “What Iranians most wished for they never gained, and what they most sought to preserve, they lost.”

What we have seen over the past two months is not the opening steps of a revolution that will topple the regime. Rather, it is another step - and certainly a significant one - drawing again from that old and deep well of discontent.

For the regime and for those who want a different Iran, the crucial moment will come when the ill, 83-year-old Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, dies. He has ruled Iran since 1989, with a combination of clever political manipulation to defuse pent-up anger - the occasional election/appointment of powerless reformist Presidents - and brutal force and the overwhelming suppression of dissent.

There are a few pretenders to Khamenei’s position, but no obvious successor, and no one who would seem to have the ability to easily hold the regime together after his death.

No matter who is appointed to the position, it will deepen divisions in the regime and provoke an outpouring of opposition and demonstrations. For the regime, it will be the most vulnerable moment since the early days of the revolution. For those who crave change, it will be the best opportunity in two generations.

In 1979, the Shah told his Generals to “Do the impossible to avoid bloodshed”, and in his memoir written from exile in Mexico he later wrote , “A sovereign may not save his throne by shedding his countrymen’s blood. A dictator can, for he acts in the name of ideology and believes it must triumph no matter what the cost”. (It is estimated that between 600 and 3,000 people died in the revolution.)

When Iranian discontent does turn into a revolutionary moment, many will die. The IRGC is the Islamic Republic. It serves the Supreme Leader and the regime. If ordered to use lethal force on a large-scale, it won’t hold back.

Subscriber+Members have a higher level of access to Cipher Brief Expert Perspectives on Global Issues. Upgrading to Subscriber+ Status now.

But therein lies a dilemma. A large-scale crackdown could strengthen the determination of the protesters. As Afshon Ostovar wrote in Foreign Policy recently, “The more people killed by the regime forces, the more hardened anti-regime sentiments are likely to grow, and the more radicalised the younger generation is likely to become… In order to win, the regime must go to war against young women and teenage girls. That’s not a war it can win”.

Once Khamenei dies, there are many directions Iran can go in: a violent uprising ending with a fragile continuation of the theocracy - possible, but unlikely; violence and the overthrow of the regime - possible, but improbable, at least in the short- term; or perhaps a more secular Iran dominated by the IRGC, brought about through an IRGC-dominated succession, with the Supreme Leader relegated to just a spiritual role (and perhaps even with the demise of the concept of Vilayat-e-faqih - the system of governance that has underpinned the Islamic Republic and that has justified the rule of the clergy over the state).

Significant change is coming to Iran. The secular nature of 70 to 80% of Iranians and their abiding dislike of the theocracy and its excesses over the past four decades makes it hard, and probably impossible, for the regime to recover its position.

When that change comes will depend on how long Khamenei lives. And the extent of change will depend on the courage of Iranians and their willingness to risk their lives.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief