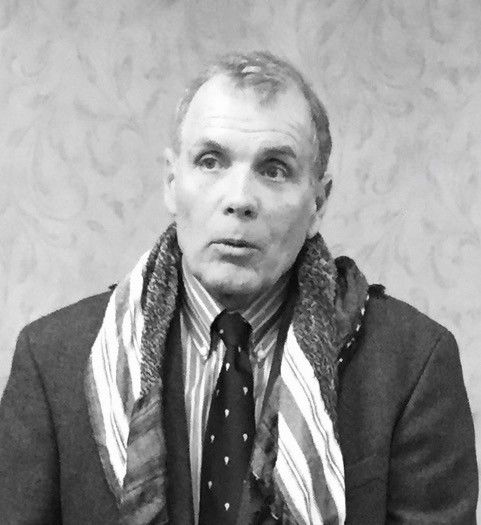

Cipher Brief Expert Doug Wise served as Deputy Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency from August 2014 until August 2016. Following 20 years of active duty in the Army where he served as an infantry and special operations officer, he spent the remainder of his career at CIA.

J.R. Seeger served as a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne and as a CIA officer for a total of 27 years of federal service. As a CIA officer, he served in multiple field locations both as a field collector and team leader.

From offering safe haven in Afghanistan for Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida to the recent attacks on Afghan Government facilities, the Taliban has represented a significant threat to U.S. and coalition forces and has been in the forefront of violence directed against the Afghan people and their government. Created by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISID) as a means to control Afghanistan without stoking Pashtun nationalism, the Taliban has been a major player in modern Afghan history over the last twenty-five years. However, the Taliban agreement is necessary for the U.S. decision to drawdown military forces from Afghanistan. We’re not critiquing that decision; but it is important to draw attention to the fact that foreign policy decisions have consequences. In this case, the agreement would grant significant freedom of action to the Taliban which would allow the group to express their historic genocidal instincts with respect to a number of ethnic groups in Afghanistan. Taliban behavior now is necessary to have confidence in the current agreement, but their agreement-governed behavior in the future is important in terms of the American core values of not abandoning those who sacrificed on behalf of the U.S.

While most of the world saw the Taliban destruction of the Giant Buddhas of Bamiyan in March 2001 as a catastrophe, what went under reported, in the years prior to that destruction, was the systematic, ethnic cleansing by Taliban commanders North of the Hindu Kush (cleansing in which one of the current Taliban negotiators, Mullah Fazl, participated). Taliban attacks on both Hazara Shia and Ismaili communities started in villages and small cities in the provinces of Samangan and Mazar-e-Sharif sometime in 1997 and ended with the large-scale massacre of the Shia community in the city of Mazar-e-Sharif in 2000. Unlike other genocidal actions of the 20th century in Africa, Asia and even in the Balkans, these Taliban actions were not designed to displace the population so that Taliban families could live in Northern Afghanistan. Rather, the Taliban stated explicitly they were conducting these actions because these two Shia sects were heretics and had no place in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The mix of multiple Sunni extremist ideologies and the Southern Afghanistan cultural mores central to the Taliban view of Islamic Law, meant the only way to maintain a righteous state was to eliminate all those (the apostates) who did not ascribe to the Taliban’s very narrow understanding of Islam.

When U.S. forces entered Northern Afghanistan in October 2001, our strongest allies came from the same Shia populations. The majority of the well-trained resistance to the Taliban came from our Afghan allies: Uzbek militia leader Abdul Rashid Dostum and Tajik militia leader Atta Mohammad Nur. Invisible to journalists and unseen by U.S. strategic commanders were the common Afghan foot soldiers who arrived on the battlefield with little more than a rifle, two magazines, and a willingness to fight and die to defeat the Taliban. These men came from Mohammad Mohaqiq’s Hazara militia and Sayed Jafar Naderi’s Ismaili militia. As special operations elements and CIA teams moved into the North, they saw village after village burned to the ground with the remnant structures salted with anti-personnel mines so that anyone who returned would be killed. These Hazara and Ismaili fighters’ sacrifices regularly made the difference between success and failure as the U.S. teams headed from Samangan in October 2001 toward the capture of the regional capital of Mazar-e-Sharif on 10 November 2001. They were also the soldiers who suffered the highest casualties in the last battle of the North in Qalai-e-Jangi Fort at the end of November.

While there have been many twists and turns in U.S. relationships with ethnic and sectarian groups of Northern Afghanistan over the years, the Uzbeks, Tajiks, Hazara, and Ismailis have remained steadfastly loyal to the larger strategic coalition effort to create a peaceful and diverse country. There are some, the authors included, who see Northern Afghanistan as a country quite separate from the lands and peoples south of the Hindu Kush. Afghanistan may be a recognized state in the world order, but it is definitely not a single nation. That said, whether a more republican government which addresses these North-South challenges is possible in the future, history tells us that the Taliban see only one solution: their complete victory with the extermination of apostates and a return to the Islamic Emirate.

Recently, the Taliban conducted a devastating attack on Afghanistan’s intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security (NDS) in Aybak, Samangan in complete contravention of their promises to reduce their attacks on Afghan citizens as they opened negotiations with President Ghani’s team. It may have been a “soft target” that was easy to attack, but to the Hazara and the Ismailis of Samangan, it also was a harbinger and promise of the terror to come when the Taliban return to Kabul as the rulers of Afghanistan. After years of effort, the NDS is one of the most diverse of the Afghan government entities and there can be no doubt that the NDS represents an apostate future that is anathema to the Taliban.

Today, the current Administration has many strategic challenges including great power strategic conflicts with both Russia and China, a global pandemic, and a World economic crisis. Its decision to end what has been a long-term war will change the U.S. role in Afghanistan. However, allowing the Taliban the freedom to attack and slaughter the Hazara and Ismaili population without any direct consequences is a replay of the mistakes that inaction made in the 1990s. The Taliban will understand precisely what inaction means: the U.S. does not care about the ethnic minorities of Afghanistan. The Taliban ideology hasn’t changed. Their leadership hasn’t changed, and clearly their Taliban tactics against diverse ethnic groups in Northern Afghanistan haven’t changed. The difference should be that we respond in a different way and in support of people who fought shoulder to shoulder with us in 2001 and 2002. The reduction in our risk must not increase their own.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief