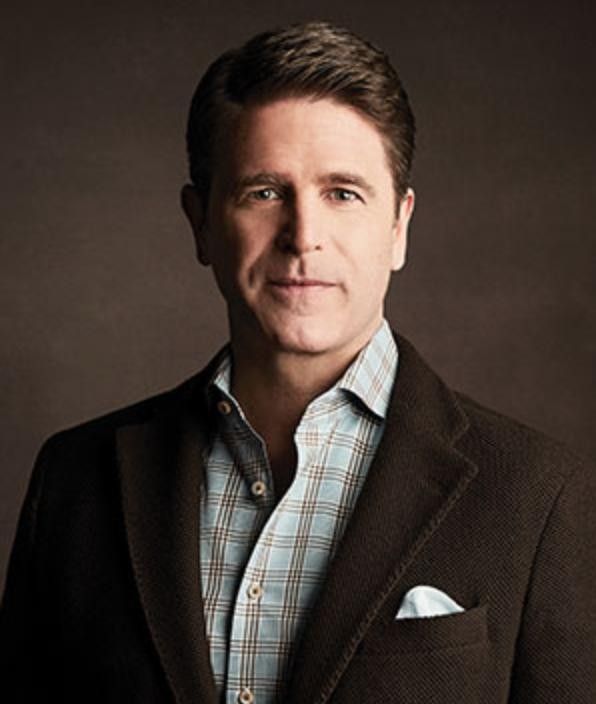

The Cipher Brief spoke with thriller novelist Brad Thor to discuss how he got his start writing, his approach to penning best-selling fiction, and the latest entry in the Scot Harvath series, “Code of Conduct.”

The Cipher Brief: What made you want to become a writer?

Brad Thor: When you ask writers this, they will tell you it’s because they had no other choice – it was the only way to give outlet to the voices in their head. Personally, being a writer has been a lifelong ambition. When I was a little boy, I didn’t want to become an astronaut or a cowboy, I just always wanted to be a writer. Wanting to write is probably one of my earliest memories.

TCB: It was on your honeymoon when you actually decided to put your ambition into action?

BT: Yes. I had initially attempted to become a writer after I graduated college. I moved to Paris with money that I had saved working in college. First writer to ever move to Paris and attempt to write a novel – I’m very proud of that. But it was very lonely, and I said to myself “This is such a lonely profession, I don’t want to do this.” I sent my laptop back home and used my money to travel around Europe. And it wasn’t that it was lonely – I was just afraid of failure. What would happen if I wrote a book and it didn’t get published or nobody liked it? So instead of facing that fear, I sent my laptop home and ran away from it. It was on my honeymoon that my wife asked me, “What would you regret on your deathbed never having done?” That’s when I told her writing a book and getting it published. There it was. My “man card” was on the table with my new wife and she said, “When we get home, you need to start spending two hours of protected time everyday making that dream become a reality.” That’s how it happened.

TCB: What were the early years like—when you were first starting out?

BT: Well, two hours grew to four, then to five, then to six, and the book tumbled out of me, poured out of me. It was like somebody had opened up a fire hose. When I wrote the climax to my very first novel, The Lions of Lucerne, it was an incredible feeling – one I have not had since – because it was that first time I had done it. I knew what people who had climbed their first mountain or run their first marathon felt. It was such personal satisfaction in having achieved that goal. But there was also a confidence that settled over me saying, “You know what, I’ve done it once, I know I can do it again. I can make a living doing this.”

TCB: You’ve written 15 novels. How do you approach each of your books and your writing process?

BT: As a matter of fact, probably the hardest part is coming up with a title. It’s really tough with so many self-published authors out there right now, and it’s hard to come up with something somebody hasn’t done before. Technically, an author can’t copyright a title, so you’ll find books that have the same titles. As far as the story itself, I’m a voracious consumer of news, particularly national security news, foreign policy issues, etc. I like to find what I think is going to be the next big thing that everybody is talking about. I want to choose a subject to weave into the books. I call what I do “faction,” where you don’t know where the facts end and the fiction begins. I try to find one subject that intrigues me and become better versed in that issue. Because if I can understand it, then I am pretty confident I can weave it into a story so that other people can understand it. I look for those types of issues out there. I’m constantly on the Internet. In fact, my wife jokes that if I wasn’t on the net so much, I could probably get two or three books written a year.

TCB: What’s the hardest thing about writing a series like the Scot Harvath series?

BT: It’s tough when you are writing a serial character because you want to reveal more of him with each book, but you don’t necessarily want him to change. I’m constantly reading books on the art of writing because I look at myself as a small businessperson. The people I work for are the readers, and I’m constantly trying to improve the product that I’m bringing them. So I’m stretching myself with each book—trying to get better. When I write a series, like the Scot Harvath series, I’m saying, to myself, “How do I peel back another layer and reveal a little bit more about him without changing him?” One of the books I read about writing talked about how you don’t want James Bond or Indiana Jones to suddenly become radically different at the end of the story. You don’t expect that kind of incredible transformation. The goal is really to enable people to see more of the main and supporting characters while still keeping them consistent. When my wife read my most recent book, Code of Conduct, she said, “I’ve loved all of your books, but your most recent one, Code of Conduct, is the best ever.” I said, “Why is that?” She responded, “Well I can see what you did with Harvath. We’ve always known what he thinks. Now we know what he feels.”

TCB: How did you come up with Scot Harvath?

BT: He’s kind of a combination of several people that I know in different positions within the intelligence and special operations communities. His last name actually comes from a friend who processes FISA warrants at the DOJ. I was looking for a great last name that nobody had used before, and I took the last name from my friend at DOJ.

TCB: Why is there only one “T” in Scot?

BT: Great question. He is named after my younger brother. I have one brother, two years younger than I am, and I was paying homage to him. My mom had chosen not to spell his name “S-c-o-t-t” because she didn’t like the idea of seeing it written down “S-c-o-t-t T-h-o-r,” seeing three “T’s in a row. She and my dad agreed to lop off one of the “T’s” in my brother’s name. I had so many readers ask me about this that eventually I had to craft Scot Harvath’s middle name, “Thomas,” and use the same excuse my mom did – that I didn’t want to see three “T’s” lined up together.

TCB: You latest novel is Code of Conduct. What’s it about, and what do you want your readers to take away from it?

BT: It’s the “faction.” I’ve been all over the board with different threats to the United States because I think there are some that don’t get enough attention. With Code of Conduct, it’s always tough for me to explain it without giving the full plot away. I wanted to bring to light a particular strain of evil that exists in the world outside. There are very powerful forces outside the U.S. that would like to see the U.S. laid low. I was talking to friends of mine in the intelligence community and the special operations community and I said, “What keeps you up at night? What’s one of the things that you’re not seeing people talk about?” And we got into a discussion about the “weaponization” of disease and what a nightmare scenario would look like. That’s what I came up with in the book and tied it to the Hajj. We’ve seen some serious public health scares that have come out of Saudi Arabia around the time of the Hajj, and I thought that would be very interesting to play with in a thriller.

TCB: One of my favorite things about the book is that the bad guys are the UN and a bunch of Washington bureaucrats led by a guy named Pierre Damien.

BT: I’m not a fan of the United Nations. I think it’s a failed organization with a lousy agenda. I’m not talking about their expressed agenda. I’m talking about their very biased anti-Israel agenda, and what I consider to be an anti-freedom agenda. As a taxpayer, I resent that we flip so much of the bill for the United Nations. I think maybe the idea was well intended when the League of Nations didn’t work out. The whole book is actually based on a real white paper that was taken out of a UN meeting high in the Austrian Alps when Ban Ki-moon brought his undersecretaries together several years ago. It was a foxnews.com reporter that uncovered this memo. Ban Ki-moon and his undersecretary generals said the biggest thing standing in the way of the UN being the ultimate arbiter and decider on global affairs was the United States, and that they needed to figure out how to get the Untied States out of the way.

TCB: You upended the conventional portrayal of private security contractors, who are usually demonized in novels, TV, and films. In your world, the contractors, led by Scot Harvath, are the good guys.

BT: I’ve enjoyed doing that. After the rise of the private military corporations, I viewed private intelligence companies as the next big thing, particularly as I’ve spoken with people who have left CIA and have been very unhappy with the management style there. I remember one person sharing with me a note on something he’d seen. He claimed it was on a cubicle where it said “Big Ops, Big Problems; Small Ops, Small Problems; No Ops, No Problems.” He thought that spoke to a very bad bureaucratic mindset at the Agency. I know there are fantastic men and women at the CIA. I have never doubted that. Are there managers that get in their way and that are more concerned with their next promotion and job security rather than taking chances? Sure. I believe that exists. I believe that there is a cross section of people and personalities at the agency. Would I love it if the Agency operated more on an OSS model and went that way and was more Bill Donovan and everything? Sure.

TCB: I also really enjoyed the Mossad angle of the story and the complicated relationship that you draw between the U.S. and Israel. How did you come up with that part of the story?

BT: Nowhere else in that region can you find a democracy outside of Israel. The Israelis are some of our staunchest allies. I have a lot of respect for the nation and the people and the fact that they are under siege 24/7. They have difficult decisions to make. Now, that doesn’t make them perfect. In the book, I wrote about Jonathan Pollard and not to forget that the Israelis have spied on us. When the Jonathan Pollard parole story broke, it was funny how many of my readers popped up on Facebook and Twitter and said, “Oh My God, I just read that in your book and now it’s on the news!”

TCB: In addition to writing, you are a conservative commentator and your political views are very much present in your story telling. Is there a balancing act there?

BT: I’ve tried not to be overtly political. Anytime you have war, espionage, statecraft, and diplomacy, it involves politics. So while I do have my own personal political views, I don’t want my books to be soapboxes. But I think the themes that you come across in my books, you do see in the real world. I try to be very real with the politics in the book because they are political thrillers. I have a particular worldview. It does seep in, but it’s not a white paper or a treatise. I want my books to be accessible to everybody, but I believe that the political things that happen in there are very reflective of what’s actually going on in DC. In fact, the first two pieces of mega-fan main I ever received - one from Newt Gingrich and then the other one early in my career from Burt Lance, who had been OMB director under Jimmy Carter - told me that I nailed Washington like nobody they’d ever read. That’s a Republican and a Democrat. So I have to be doing something right if both of those guys said I’m getting the threats and the insider stuff correct.

TCB: Can you tell us a little bit about what you are working on next?

BT: (Laughs). No, and I appreciate the fact that the Ludlum Estate and the Clancy Estate are so well thought out that they would plant that question in this interview. Obviously I’m teasing. I never talk about them. My friend David Morrell—he’s probably one of the greatest thriller authors ever—said that when you talk about what you’re working on it takes a little bit of the fuel out of the rocket boosters that get you through the year of writing it. Like I tell people, when your wife is pregnant, you shouldn’t be talking about the names of the children that you’re thinking about. Don’t talk about to anybody because everybody has at least one bad experience with someone with that name. I never talk about the projects outside of with my editor until it’s complete and ready to go to market. But I will tell you, the next book will be the most current that I’ve ever done. What I’m hoping to do, if I can get off social media long enough this year, is to write a Scot Harvath book and a parallel Athena Project book about an all-female delta force unit. My goal is to get two written this year if I can that will both deal with the same plot, but from different angles.

TCB: Could you tell us a little bit about your movie company?

BT: Currently, we are in the process of writing a screenplay. We spent several years soliciting different private equity funds to get enough money to be extremely competitive in Hollywood. That is not to say that we won’t partner with another company—whether it’s for distribution or as an equity partner—but we spent a lot of time and found the right groups to put into our venture. Now we are developing my very first novel, The Lions of Lucerne, and the screenplay is being written right now.

TCB: Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future of publishing?

BT: There is always going to be a market for great stories well told. We are starting to see the balancing out of e-readers and actual printed books. There was a big surge with e-books. 70% of my business is on “e.” I’m a technology guy. But, there is an advantage and a disadvantage to e-reader. The advantage is that someone who has finished your book at two in the morning can click a button and download the next one. That happens a lot. People say, “That was a great book, I want to start the next one,” and they can do it immediately. The disadvantage is that when someone’s reading on an e-reader, you can’t see what he or she is reading because you can’t see the cover. You can’t say, “Hey, I just finished that Brad Thor book, what part are you at right now?” Or, “I was going to start reading that, but I need to finish the last one. How do you like that book?” We lose that connectivity that exists by being able to see what the people around us are reading. Or seven people on the bus you saw over this week have that new Brad Thor book, it must be awesome, I’m going to go get it. We lose that. So there is an advantage and a disadvantage. I’m very bullish on great stories well told. There is always a marketplace for those.