From day one, South Korea’s new President, Moon Jae-in, has shown he will be a different type of leader. He confirmed a campaign promise that he would consider visiting Pyongyang before Washington to tackle the North Korean nuclear issue, albeit only if the conditions were right. He has said he will not work from the palatial Blue House, the office and residence of previous presidents, and will instead keep his office in downtown Seoul.

A different sort of leadership is what South Korea voted for. After two conservative administrations, and with the second ending in the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye for her involvement in a corruption scandal, Moon won 41 percent of votes. In a field of five candidates and with second-place conservative candidate Hong Jun-pyo only gaining 24 percent of the vote, Moon won by a wide margin. His landslide victory demonstrates the electorate’s desire for a new direction guided by the liberal Democratic Party’s platform of wealth equality through economic reform, strengthening the social safety net, and engagement with North Korea.

Moon has espoused these ideas throughout his career. As a former human rights lawyer, he was barred from becoming a judge due to his record as a protestor against the South Korean dictatorship. He befriended fellow lawyer and future Democratic President Roh Mu-hyun, South Korea’s last liberal president. When Roh became president, Moon became his chief-of-staff. Moon first ran for office in 2012 and won a seat in the National Assembly. That same year, Moon ran in the presidential election and lost to Park Geun-hye by only 3 percent of the vote. Despite the loss, Moon established himself as a moderate with the backing of the younger generation and became leader of the Democratic Party in 2015. Moon’s distance from conservative politics and his strong popularity among younger South Koreans carried him to victory in the May 9th election.

Moon’s first acts and statements as president have been to reassure South Korean citizens and the governments of the United States, Japan, and China, however, his administration has an uphill challenge before it can establish a new normal.

At home, the public’s optimism in the new administration is tempered by distrust and fears over continued corruption and collusion between government officials and the chaebol—South Korea’s family owned conglomerates that dominate the economy. In the National Assembly, Moon’s party only holds 40 percent of seats, and any policy reform will have to be achieved through cooperation with other parties. James Kim, the Director of the Asian Institute’s Washington office, told The Cipher Brief the Democratic Party’s lack of seats “will stand in the way of important reforms in South Korea until 2020, when the next general election is scheduled to take place.”

Looking abroad, Moon’s most pressing challenge is to assure the U.S., Japan, and China that his government can cooperate on North Korea policy while reasserting South Korea’s leadership role on this issue. After Park Geun-hye’s suspension as president and subsequent impeachment, Seoul took a back seat at a time when the Trump Administration was more aggressive in addressing North Korean missile launches and the possibility of a sixth nuclear test, escalating regional tensions with Pyongyang. On top of that, Moon will try to change course on North Korea policy away from sanctions and isolation of the Kim Jong-un regime and reintroduce negotiations and the possibility of reopening the Kaesong Industrial Complex, a joint economic venture between North and South designed to foster cooperation and mutual prosperity. The complex was closed in 2016 by Park in response to a North Korean rocket launch.

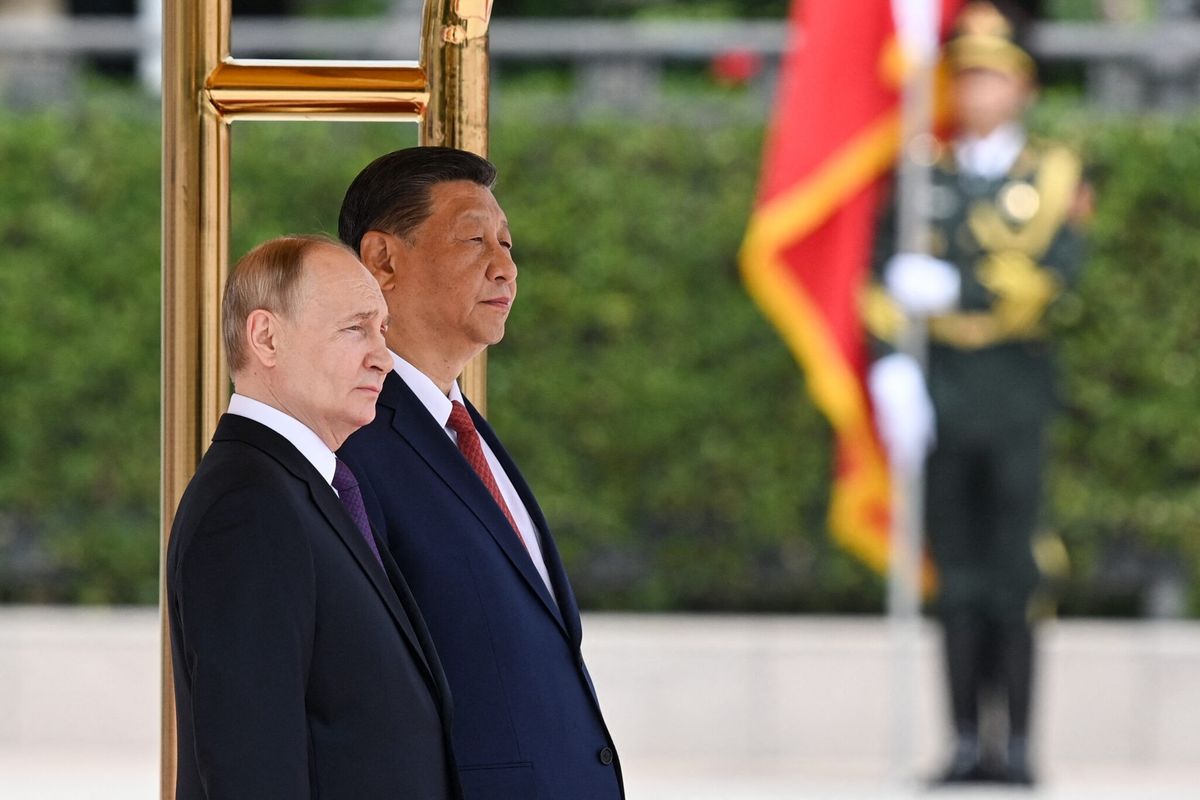

The Moon Administration’s first statement on North Korean policy proposes a balanced approach. A spokesman, quoting a statement Moon made to Chinese President Xi Jinping, laid out a preliminary plan, "The resolution of the North Korean nuclear issue must be comprehensive and sequential, with pressure and sanctions used in parallel with negotiations."

It remains to be seen how Moon’s North Korea policy will align with that of President Donald Trump. While both administrations seek the complete and verifiable denuclearization of North Korea, they are not in agreement on the options or sequence of events to get there. Trump has made clear that all options, and notably military options, are on the table, while Moon sees military force as a last resort and only at South Korea’s say so. The U.S. wants to see concessions out of North Korea prior to negotiations, whereas Moon’s comments suggest he is prepared to do so with fewer preconditions.

As Moon reasserts South Korea’s role in dealing with Pyongyang, these differences in North Korea policy may produce friction within the U.S.-South Korea alliance. In the past, a conservative U.S. president and a liberal South Korean president have been the least fruitful for progress on North Korean denuclearization. President George W. Bush’s early hardline stance on North Korea clashed with then-South Korean President Kim Dae-jung’s “Sunshine Policy”—an engagement approach that advocates negotiations and rewards for North Korea’s compliance with denuclearization, such as the creation of the Kaesong Industrial Complex.

As a member of Roh’s administration, Moon was an advocate of the Sunshine Policy and this will likely carry into his administration. Soo Kim, a former CIA analyst, told The Cipher Brief that “the broad contours of his policy views throughout his political career suggest he’ll stay closely aligned with long-held South Korean liberal views in dealing with the Kim regime.”

While the broad strokes of Moon’s policy may in time put him at odds with the U.S. approach, he has so far shown capacity for compromise with the United States. As a candidate, Moon called for a review of the decision to deploy THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense), a U.S. missile defense system that has been publicly unpopular and drawn the ire of China. Yet in his first conversation with Xi as president, Moon said the dispute over THAAD could only be resolved once North Korean provocations had ceased.

Moon Jae-in has come to power at a critical time in the history of South Korea’s democracy. He ran on a platform of change for both domestic and foreign policy and the promise of improving South Korea’s prosperity and security. However, with the array of foreign and domestic challenges and a minority in parliament, his success in bringing about change may hinge on his ability to compromise rather than reform.

Will Edwards is an Asia-Pacific and defense analyst at The Cipher Brief. Follow him on Twitter @_wedwards.