The arcane art of measuring the health of civil-military relations is experiencing a renaissance. Although it is welcomed by those who practice it, the reasons for the renewed focus are less so. Contributing factors include 15 years of continuous wartime deployments and the lack of a shared experience between the general public and the small percentage of Americans who have served or whose family members have served. Add on to that more recent tension over the obligation of military personnel to obey presidential orders regardless of legality, as well as the role of retired senior military officers in the electoral process, presidential transition, and in populating the Trump administration, and you have the makings of a potential civil-military crisis.

Enter Jim Mattis, née General and now Secretary of Defense. It is not without irony that Mattis is seen as one of the Trump administration’s foremost diplomats rather than a “mad dog” military man. Perhaps that perception reflects the low bar for American diplomacy today, but I believe Mattis deserves more credit than that. He has moved with a sure and steady hand to underscore the full faith and credit of the United States to allies, friends, and foes alike. If only the White House could follow his example.

Despite these positive signs, having a former senior military officer as secretary of defense will present challenges for both the man (in this case) and the institution. He has already passed the first major hurdle: receiving legislative relief to serve in the first place (in full disclosure, I testified before Congress in favor of granting such relief for Mattis). Now his actions on the job will determine whether such a waiver ultimately aids or undermines our principle of civilian control of the military.

Foremost among the signals Mattis needs to send is that he values the input and advice of his civilian staff. The Department of Defense employs almost 750,000 civilians, far less than its total military cohort of more than 2 million but a substantial number of invested stakeholders by any measure. Secretaries of defense, even ones without previous military service, sometimes overlook the input of civilians and rely heavily on military subordinates – although some, like Donald Rumsfeld, seem to do the opposite. Civilian defense professionals are highly sensitive to this dynamic, as they should be. Secretaries come and go, but the civilian cohort remains and is institutionally critical to maintaining civilian control. Recruiting and retaining the best and brightest civilians requires ensuring they see themselves as valued contributors. This is a key reason why leaving the top defense posts for people drawn from civilian life has helped generate the world’s most vibrant defense community in the United States.

Secretary Mattis’s discussions in Japan may provide early evidence that he will in fact rely on his civilian advisors for complex political-military issues, even when they may be in conflict with some military advice. Mattis is surely well versed in the negative view the Marine Corps has historically taken toward the long-standing plan to relocate Marines from Futenma Air Base in Okinawa to a new Futenma Replacement Facility and to Guam. It is noteworthy, therefore, that the press release from Secretary Mattis’s recent trip to Japan included an unequivocal commitment to the Marine realignment plan that his civilian staff helped develop hand-in-glove with Japanese counterparts.

If ensuring adherence to civilian control, including by developing and retaining a professional civilian cohort, will be the first half of Mattis’s civil-military legacy, the second half will be valuing the military profession. This may seem like a slam-dunk for a former general who served more than 40 years in the armed forces. However, the temptation could be great to substitute one’s own well-honed professional military judgment for that of those still in uniform. It’s a blessing when a secretary of defense comes to the table as an educated consumer of military advice; it’s a curse when the secretary of defense, his civilian advisers, or those elsewhere in the national security enterprise attempt to usurp the senior military’s role. It is not yet clear the degree to which the Trump administration is relying on the operational input of the military. An early test might be whether there is evidence that the administration is taking into account the input of General John Nicholson – who recently recommended the expansion by a few thousand of U.S. military personnel training and advising Afghan security forces – in its development of Afghanistan policy. Doing so need not mean providing the forces that General Nicholson has recommended; rather, it means showing that his advice has been deeply considered and weighed alongside other factors

This administration’s imprint on civil-military relations will extend well beyond the implications of Jim Mattis’s appointment as Secretary of Defense. Although its dynamics and personalities will evolve over time (as they have even this week), it is worrisome that the administration begins its tenure with a disproportionate number of former military personnel at the top echelons of its national security team, and thus relatively few trained in other disciplines.

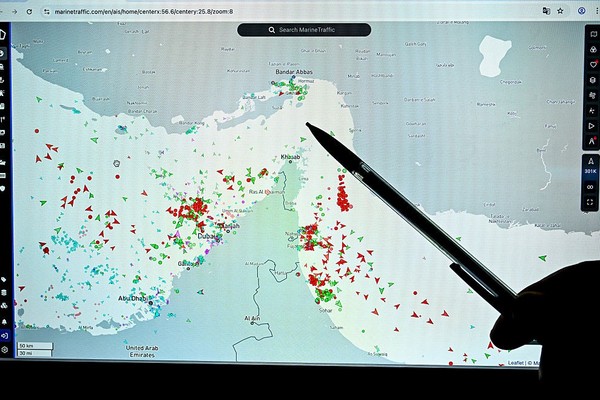

The United States faces a world in which potential foes are seeking to stay below a threshold that might trigger our military response. This puts pressure on us to hone a new national security toolkit that draws on the advantages the United States can bring to bear below the level of violence, including alliance management, counter-threat financing, public diplomacy, governance assistance, cyber defense, and public-private partnerships. A national security community led largely by recently retired military officers may appreciate this problem set, but their professional backgrounds and networks may be insufficient to address them.

So it is that even if Secretary Mattis deftly navigates the choppy civil-military waters in which he finds himself, the broader administration approach of filling senior-level positions with retired military is creating incentives within the uniformed ranks that will not be easily or quickly reversed. The nature of the work at these highest policy levels is inherently political. It is not unusual to have some current and former military persons serving in such positions—having defense expertise in the mix is vital—but the Trump administration’s strong bias away from civilians in these positions is unprecedented in the modern era. Short-circuiting opportunities for civilian national security experts undermines the cadre’s development, and thereby weakens one of the most important expressions of the American approach to civilian control. It also risks substantial politicization of the force by further inclining those in uniform to believe there are career advantages to be had in pleasing political patrons. The ultimate irony of this course of action is that by raising senior former military professionals so prominently into the political echelons of our national security structure, we are actually eroding the armed forces’ professional military ethos over the longer-term, and with it the quality of military advice on which we rely.