SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW — Over the weekend, Ukraine said its forces were encircling Bakhmut. Russia, meanwhile, congratulated its troops for taking the embattled Ukrainian city. It is precisely these types of conflicting accounts that policymakers need clarity on. And they often turn to the CIA to provide it.

Helping to parse fact-from-fiction, CIA's former Deputy Director for Analysis Linda Weissgold's 40 year career at the agency spanned evaluations of Ukrainian battlefields, Iranian nuclear programs, and the long game threats being posed by China, to name a few – the latter of which she gave special attention during a recent interview with The Cipher Brief.

“I think at this point what we can say is that America's position at the head of the table is no longer guaranteed,” she said. “What we've seen is that China is not just content to have a seat at the table. President Xi wants to actually be at the head of the table.”

In a wide-ranging conversation, Weissgold offered up fascinating insights into what makes for good analysis, how artificial intelligence factors in, and the very nature of how the agency itself is (and should be) changing.

The full brief was available live for Subscriber+Members. The transcript below is a portion of the full conversation and has been edited for length and clarity. Watch the full video here.

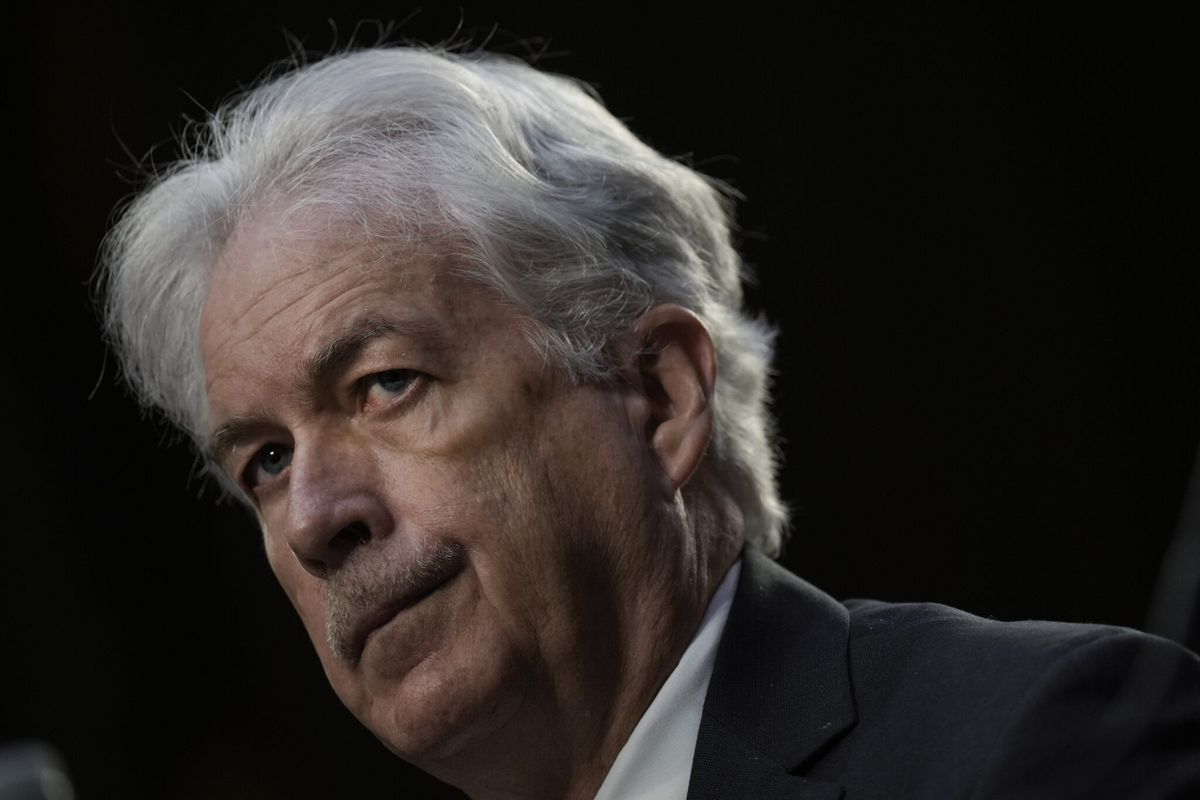

Linda Weissgold, Former Director of Analysis, Central Intelligence Agency

Linda Weissgold was the CIA’s Deputy Director for Analysis from March 2020 until mid-April 2023. In that role, she was responsible for the quality of all-source intelligence analysis at the CIA and for the professional development of the officers who produce it. Since joining the CIA in 1986, Linda has been part of the creation and delivery of intelligence analysis on a variety of complex issues and in multiple settings. Before the 9/11 terrorist attacks, she was an analyst and leader of analytic programs focused on the Middle East. Immediately afterward, she was among those that volunteered for counterterrorism assignments. The units she guided, including as the head of the CIA’s Office of Terrorism Analysis, generated insights that informed US policy and operations across multiple Administrations. And for more than two years, she served as a Presidential intelligence briefer.

The Cipher Brief: Today's world is incredibly complicated. How does the CIA even begins to think about understanding it all?

Weissgold: When we talk about an increasingly complex world, I don’t think that that’s a hyperbole. We really are in a transformative moment right now on the global stage. Today’s world is more complicated. It’s more crowded and competitive than I’ve ever seen during my almost four decades working at the agency. That presents both some real challenges and some real opportunities for intelligence analysts and how we think about things and what we do.

I think at this point what we can say is that America's position at the head of the table is no longer guaranteed. What we've seen is that China is not just content to have a seat at the table. President XI wants to actually be at the head of the table. There are declining powers like Russia that, I think the war in Ukraine has shown, will probably rather than give up more power, would want to upend the table altogether at this point.

Then you have a bunch of countries that are caught in the middle — whether it's the Middle East, Africa, Latin America — that are really trying to hedge their bets and are trying to preserve their ties without alienating rival powers. Helping our policy makers through all of those dynamics would be hard enough for CIA analysts. But we're also contending more and more with some really important transnational issues. Things like climate change, food insecurity, migration, counter-narcotics issues, global health.

That's taking up more and more of our time. We can't take our eyes off the ball on terrorism. Then you throw in the unprecedented technological change that is happening in our world. Really that's reshaping both the substance and the process of how we do our analysis.

We provide historical context, we highlight motives and variables and we sketch out scenarios. Then we identify potential points of leverage that our policy makers and decision makers can use if they so choose to. It's really important to make sure that folks understand that analysts, particularly at CIA, our job is not to make policy. Our job is to inform policy. Some might think that's a limitation, but for us, we actually think that there's power in that. Because if we can objectively inform, then we have a better chance I think of people listening to us.

The last point is how we do our jobs. It sets us apart from the media and think tanks … because unlike them, we rely on I guess three points of privileged access. We rely on access to the time and the thinking and the goals of our country's leaders. This helps us understand what they need to know and when they need to know it. That was part of my responsibility for both having briefed the president but also to the last several years being the one who helped set what was going to go into that briefing every morning. Knowing what's on there, what they're dealing with is very important. The second thing is, access to a vast range of information, be it classified and unclassified. That's often acquired at great risk and cost, but it gives us the raw material to evaluate for our analysis. It's really a big sandbox in which we can develop insights. The last thing I'll just say is that it's the access to CIA's reputation. This gets us a place at the interagency table and the opportunity to be heard. We have to be mindful every day about that reputation.

Looking for a way to get ahead of the week in cyber and tech? Sign up for the Cyber Initiatives Group Sunday newsletter to quickly get up to speed on the biggest cyber and tech headlines and be ready for the week ahead. Sign up today.

The Cipher Brief: You began in your role as CIA's chief of analysis just as COVID became a known issue. How have you seen the gathering of intelligence, the analysis, and the sharing of intelligence, change in the era of COVID?

Weissgold: Taking over right at the beginning of COVID, there were a lot of challenges involved in that. From both the managing the workforce and delivering information to policy makers. During that time, we also can't forget that the entire time in 2020, we also had a new administration coming in and it's always difficult when you have new administrations. Because you are still serving one administration and you are preparing another.

I kept threatening that I was going to get a T-shirt that had 50% on any given day. I only had 50% of people in the office, because that was how CIA chose to work through the pandemic. Because we couldn't work from home. Classified information, folks couldn't do it from there. What we did was go to a week-on-week-off schedule for quite some time. We thinned out people in the building to be able to give people more space.

One of the things that really helped us was that we had already been anticipating not the global pandemic, but the idea that we would have to look at how we do our work differently. That was part of my job to be making sure we were always ready for the next big thing.

For example, from a workforce perspective, we had already set up ways in which we could find out what people's expertise was, even if they weren't working on that account. We had an ability to know that maybe even before you came to CIA, you worked on a particular issue or you spoke languages that you weren't using now and we could tap into that expertise on your week you were there. We had already set up some systems along those ways to understand our expertise. We had set up knowledge management tools in which we could quickly go through and have people follow what the analytic lines were and how they change over time ... 10 years from now there's going to potentially be something bad that happens. What does this mean for China's economy? What does it mean for our own economy and how we're going to be able to [examine] our own budgets, and how we're going to be able to maintain leverage and power across the globe? We had to continue to try and look ahead, but doing it with half the people. I am blessed to have had CIA's officers are truly mission focused. People often ask me why I stayed for almost 40 years. It was the mission. But it was also the people. They are amazing in their ability to stay on mission despite everything going on around them.

The Cipher Brief: What worries you today about AI?

Weissgold: I do not think that AI is going to replace CIA analysts anytime soon. We have to be very clear about why we think what we think. You have to be able to explain that. I don't think it's going to be a satisfactory answer to any President of the United States for CIA to come in and say an algorithm that I don't understand says so.

We need to be able to say why we think what we think. But AI, I think, is going to be a tool that we will use. We already have been using AI at CIA for quite some time. We've developed some of our own. Though, it's also going to make our lives more complicated. Deception is going to be even harder to uncover in a world in which people have access to AI.

Another reason I don't think that AI is going to replace us is that — I think folks are already starting to see as more and more people test AI — as a large language model, it's going to give you inaccurate answers at times. It doesn't know whether what it's saying to you is actually correct. It just knows that that is what a lot of people have said. Again, it doesn't have that expertise to be testing itself, which is again part of what our analysts do. I look at AI as both it's going to be a tool that we'll use in the future and it's also going to be something that we're going to have to be able to identify and uncover when it's being used against us.

Our reputation is so important. A quick little story. It wasn't from AI, but it does get to that idea of accuracy of what we do. One day when I was briefing President Bush, I walked in and before I could start my brief, he stopped me and he asked the question. He was a little upset because he had just had a protocol visit. He had a state visit with someone and he had given them, as a protocol gift, a bowling ball engraved. That world leader looked at him and said, "But I don't bowl." He was embarrassed and he asked his staff, "Why did you have me give this guy a bowling ball?" They said, "Because CIA said he was an avid bowler in his leadership profile." The President of the United States first thing in the morning looking at you and saying, "Why the hell did you say that?" Getting back to what is really the bedrock for us, which is that trade craft of being able to say why you said what you said.

I went back that morning and sure enough, our folks had done their trade craft. They knew why they said what they said and it was on this world leader's official campaign website when he was running for office. He said he was an avid bowler. Not only that, he was president of his local bowling league. There were all kinds of things on his website. I think he was trying to be a man of the people. The fact that I was able to go back the next day and tell the president that here's why we said it. But if I couldn't do that, if I had to go back and just say, I don't know, Chat GPT told me, that wouldn't work.

It is one of the things when you're talking about in a world where we're increasingly seeing disinformation and misinformation. That part of the way, getting back to your very first question of how CIA analysts do their work, we are by nature, I think a group of skeptics. You look at everything with a skeptical eye. At the same time, you have to be open to the idea that the way you think about the world and what you've been thinking could be wrong. Probably the most important question that our analysts have to ask themselves every day is, how might I be wrong? Some of it may be just because it's on the website, that doesn't mean it's true. Most days we also don't get to defend ourselves afterwards.

It's not just for the President anymore. Are you getting your daily national security briefing? Subscriber+Members have exclusive access to the Open Source Collection Daily Brief, keeping you up to date on global events impacting national security. It pays to be a Subscriber+Member.

The Cipher Brief: Can you explain a bit more how large language models like Chat GPT could actually be helpful to intelligence analysis trade craft?

Weissgold: Analysts these days are swimming in oceans of information. I sometimes would tell the story that when I started you could actually hit next doc on your computer and there wasn't one. You had read your mail for the day. I know that our analysts today can't even conceive of that.

Also, we continue to have global coverage responsibilities at CIA, but there are some countries where we can't spend as much time looking at them. Having something where you have an analyst who can check in every once in a while. Or have the machine alert you when something has happened on that country, if you set up parameters. Again, we've been looking and have been working through those kinds of models as well. I could envision a lot of ways in which AI will be able to help the analysts. I love the idea of red teaming. I'm a little less enthralled by the idea of having it do the initial draft.

But again, part of I think what's going to be so important is what's the prompt that is used with the AI? Because for us, when you're coming up with an analysis, one of the most important parts at the beginning is what is the key intelligence question you're trying to answer? You don't know what that answer's going to be. But forming that question is really important. Forming that question for the AI will be really important. You have to see what happens, what they would come up with. Whatever you get is the basis, it's really hard to change it. You can evolve it a little bit, but I would prefer to see analysts taking that first rough draft.

The Cipher Brief: What is your general strategy in validating information with regard to deep fakes and other disinformation?

Weissgold: We're going to have to develop our own technological responses to help us figure out and identify deep fakes in others. But some of this is part of the trade craft that we use already. I believe very strongly that coordination and real debate is a key part of uncovering misinformation even today.

When an analyst at CIA writes a piece that they believe is going to go to the policymaker, it starts out as an individual product, but it ends as a corporate one. By that I mean by the time it is done, it has been tested through their team and debated. Depending on who the customer is, if it's going to the president, it has gone to other parts of the intelligence community for them to weigh in and debate and ask questions. What about this? Did you see this? Did you consider maybe that video was a deep fake? We have information over here. It really gets tested and vetted as best we can.

Then the other part of it is, it's really key for us to make sure that we tell policy makers our level of confidence in what we're saying. In addition to telling them about why we think what we think, we have to tell them how sure we are about it. This is really one of the big lessons that came out of Iraq WMD for us. To be much more clear on consequential judgments. To make it clear just how confident we are.

President Bush used to ask me if folks from across the intelligence community are all seeing the same material. It was okay with him that we reached different answers, but he wanted to know why. Again, getting back to that really hard thing of why you think what you think. Having to be able to come down to because I'm placing more emphasis on this source or past precedent. Or I have doubts about whether or not that source is real and being able to explain that to our policymakers.

The Cipher Brief: The line between making policy and informing policy has the potential to be somewhat blurry. How do you manage that?

Weissgold: Being objective is not easy. Every analyst in the intelligence community has their own personal views. It's not like we become automaton the minute we walk in the door. But what you have to understand is that your personal views, you have to set those aside when you are looking at an issue. It doesn't become about is it a good or a bad thing that something's happening in the world. It's just a thing. You are talking about that issue.

One of the reasons I said it's really important for folks to understand what you do and don't do as an analyst at CIA is because if this isn't the right fit for you, then you shouldn't be at CIA. It's not about us ever saying, “we think that the best thing you could do in X country is this.” [But rather,] “if you do X, we think Y is going to happen, which is actually opposite from what you said you wanted.” Again, doing all that without a value judgment is really what our objectivity is about.

In one of my jobs, I was the head of our office of terrorism analysis. When I took over there, one of the very first things I did was to bring together our senior analyst within that office and ask them to do some structured analytic techniques to try and figure out where we thought terrorism would be five to 10 years from now. Because I said I needed to do that because from a strategic planning perspective, I needed to understand where we thought terrorism would be 10 years from now. Because I needed to start hiring and developing that expertise now.

Absolutely those kinds of brainstorming and structured analytic techniques are really important. One of them that I really love is the what if idea and how you get to it. If you wanted to say something has occurred, pick your topic.

Let's say we were able to stop the flow of fentanyl into the United States. Then what are the things that would've had to have occurred? You go back and say, what would've had to have happened to make that goal real? And break it apart. Then say, okay, now we've got the things that we can really start writing on and planning for. If you want to take those individual pieces and say, in order for that to have happened, we would've had to have understood all of the supply routes by which it's coming in, we'd have to understand what was going on with the various cartels, what was happening in China. Then you can really start for planning purposes and strategic development purposes, and use the structured techniques.

The Cipher Brief: Once you retire this summer, where will you turn for sources of trusted information about what's happening in the world? How will you continue sorting fact from fiction?

Weissgold: That's where I think a lot of the training of being an analyst is going to come in. I'm going to tell a story. I'm going to brag on my husband for a minute. My husband was a military analyst at the agency for many years. He's since retired. When the war broke out in Ukraine, he couldn't help himself. I would come home from work and he'd have maps out. He was very into order of battle over the years. Purely on open source information and his own expertise, understanding what are those questions that we should be asking?

What are the things that need to happen in a battle? What are the kinds of things that we could be expecting the Russians to be doing? Where the field hospitals would need to be? All of those kinds of things combined with the expertise. I would come home and he'd have gotten to 85 to 90% just on open source alone and his expertise as a military analyst, and the way he reads information, again, with that critical eye of saying, I don't have anything to back that up, would I think that I would be able to see something about that? Should we really have an expectation that if this was happening, someone would've seen the field hospitals? Those kinds of things. I do think that I'm hoping that my own training is going to kick in and I'll be able to look at that from a perspective of ... I just don't think we read the news the same way the average person does. As I said from the very beginning, we read it very skeptically.

The Cipher Brief: There are some folks in the private sector who say that the agency and the IC in general could do a better job of institutionalizing the way that they're using open-source information. What do you foresee about information or getting information 5, 10 years from now? What do you think some of those major tectonic shifts are going to be?

Weissgold: A couple of things. I know there are a lot of folks out there who are talking about that there should be an agency for open source or there should be a more centralized approach to open source. I take a counterpoint to that. I would prefer, again, that the analysts have access to the tools and the methods themselves to be able to what I call wallow in the data. Again, this comes from a bit of those dinner conversations with my husband about order of battle.

When you have someone who has expertise and they're really wallowing in that data and they have that intellectual curiosity to look and say, never seen the tank up there, I wonder why there's a tank there now? Really start digging into that. That's where new insight comes from. Often that's the way I describe the job of an analyst. It's to create new insight. What I fear is that people want to move in a direction with open source in which somebody else is curating that all and delivering it to analysts.

What that feels like is very much going backwards. Again, when I started at the agency we didn't have all of the search engines and tools, we didn't have the internet. But I recently went back through my own evaluation reports as part of my retirement and I was praised for being an early adopter of the internet. But you would go to the library and you would ask the librarians, hi, I'm going to be writing a paper about X. They would do some searching with the tools that they have, tell you come back in a couple of days and they would hand you things. I remember I was always the one going, "What didn't you give me? What did you curate out?" I don't want to go back to that. I want the analyst to have as much access to that whole sandbox of information to be able to find the insights themselves. I think that's my first point.

The kinds of things that I think we're going to find that five, 10 years from now ... it's already happening. We have imagery, that is commercial imagery, that is out there that you can look at. It's so hard, and I feel for our operational colleagues at the agency, it is so hard to keep anything hidden these days. There's someone watching on security cameras and CCTV everywhere you go. All of that kind of stuff. I do think it's going to be ever more information out there for the analyst. It's just going to be figuring out how do I get to the stuff I really need?

Then the last thing I'll just say is maybe something you weren't thinking of. But it's the opposite side of this. How are we going to disseminate the information once we get it? We're already working on things like virtual reality and having augmented reality and all kinds of things so that we can present to policy makers information in different ways. Now, getting them to actually put on the goggles, that may be a challenge. But we have to be ready when we have a policy maker that is ready for that.

How they take in information is driven by the press. It's driven by the outside world. It's already a question of do they want to swipe or do they want to toggle or do they want it on an iPad or paper, all those kinds of things. We have to be ready for that part too. How we're going to deliver that information to them. I was once asked, what job do I think will exist at the agency 10 years from now that isn't there today? I have a feeling it's going to be, we already have a few, but we're going to be need a whole lot more folks who are doing virtual reality and folks who are helping us through that dissemination of our product.

As a Cipher Brief Subscriber+Member, you have exclusive access to virtual briefings with leading experts and top officials in the national security and intelligence space.

Subscriber+Members receive invitations to register via email.

Be sure to join us at our next virtual briefing.

The Cipher Brief: What secrets or tips do you have to share about sussing through all of the data and getting down to what's important?

Weissgold: Don't underestimate visualization tools for data. Because I think that it's one thing when you are spending time going through rooms of paper. Much of the data now is actually coming in and something that may not really make a whole lot of sense to an analyst looking at it. It's just a bunch of geo coordinates or something along those lines that was left on the cutting room floor at NSA or something.

But yet when you're able to take that information, clean it up and use visualization tools, it shows us all kinds of things that we were missing before. I think the use of visualization as a way to help put together. I know this sounds corny, but to put together that picture that's coming from those oceans of information, that would be a secret. I think we're finding that that's really helpful for our officers. The other is that idea, as I said, of being able to set some parameters about if you've done your thinking beforehand.

The Cipher Brief: There must be some lighter moments over the years. Can you share any personal stories from your time as a presidential briefer?

Weissgold: I feel very strongly that the relationship between a briefer and their principal is something that there has to be confidentiality. I did ask President Bush if he was okay if I start to tell a few stories about him, and he said, "Absolutely." I recently was invited down to do a session at the Bush Center, and what I didn't know is that he was going to be in the front row when I told this story.

But it was about the first time that I briefed him. What he did want to know was whether or not I could, quote, unquote "take the heat."

The idea being that he could be himself in front of me. He could ask hard questions. He could do things. My second day that I was going to actually do my first briefing after I having met him one day, I watched my predecessor do her briefing, then I was going to do it. As I was prepping — and it was a lot prepping for finals every morning, you're really cramming it in trying to figure out — his aid walked in with this box and mumbled something about it being toys for Barney, the dog.

We were actually down at the ranch in Texas and not at the White House. He puts this box down and I'm about to brief the President of the United States. I do the briefing, and after the briefing was done, the president asked me if I could get something out of the box. I was like, "Oh, okay, you mean one of Barney's toys? Sure." I went and I opened up the box and it was rigged to have a fake snake jump out.

The snake jumps out now and I am not a jumpy person. I opened the box, the snake jumps out, I turned it over. I looked at the president and I said something to the effect of, "Sir, I think Barney got this one already." I closed the box. He got this little smirk on his face. Never said a word after that. He walks out and then his aid, the one who carried the box in comes up to me and he goes, "What do you have like ice in your veins?"

I said, "No, I have an eight-year-old and you're going to have to a whole lot better than that." That was like your test and it was fine. There are lots of moments, lots of things happen in a career at CIA that you aren't expecting. It's one of the beautiful things about it. If you get good at your job there, it's all about your competency. It's one of the other reasons that I stayed. It's not about your seniority, it's not about anything. It's about whether or not you know the most about what's going on and you're the person who's going to get the opportunities.

Read more expert-driven national security news, analysis and opinion in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.