Japan has the means, motive, and opportunity to produce nuclear weapons. However, as a matter of long-standing policy, Tokyo has kept its options open, as long as it can rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The perception is widespread that, due to its history as the only country upon which a nuclear weapon has been used, Japan has an innate nuclear allergy that precludes it from going down the path of nuclear proliferation.

This is partially true, but Japanese leaders have also preserved Japan’s nuclear option both by carefully and consistently articulating Japan’s policy in this regard, and by nurturing Japan’s actual capacity to produce and deploy nuclear weapons. In addition to its intrinsic merit, this nuclear latency approach serves to convince the U.S. that it must continually reassure Japan of the credibility of its nuclear umbrella to prevent Japan going nuclear.

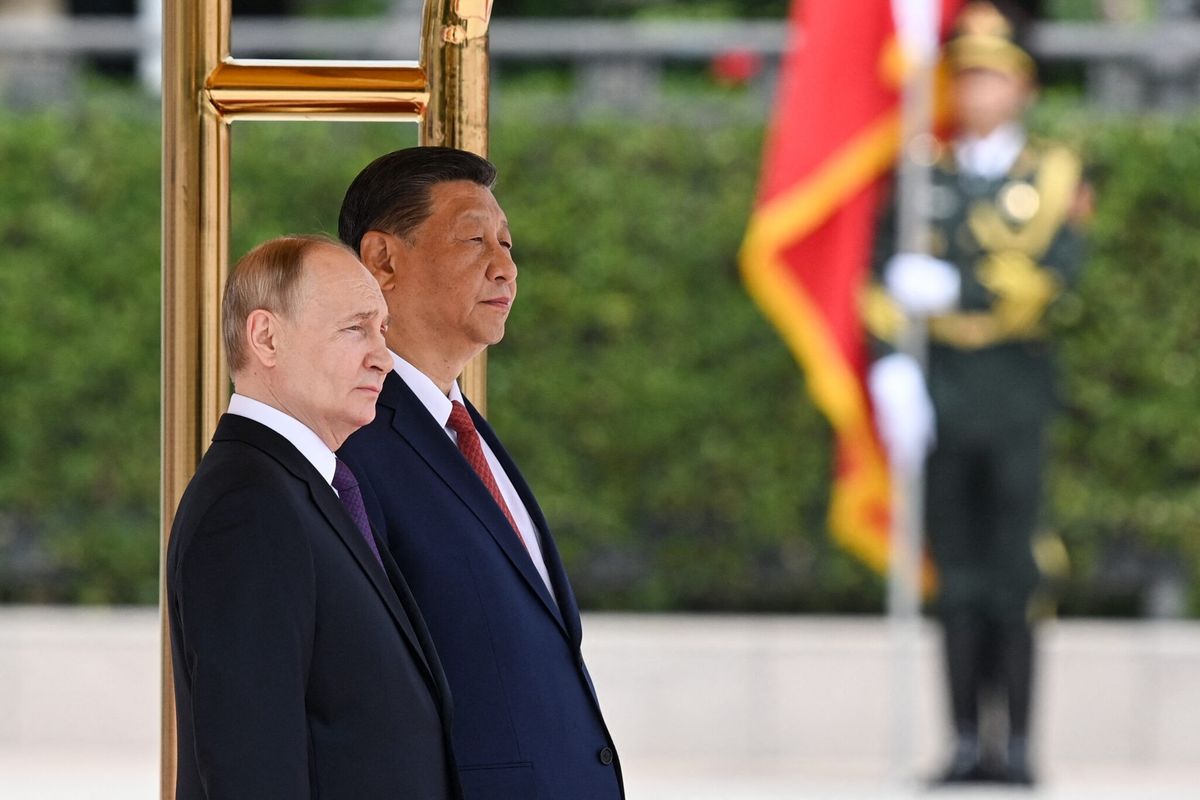

Given the dense concentration of the Japanese people in relatively few urban centers, Japan is particularly vulnerable to nuclear and other military strikes. Japan’s alliance with the U.S. – its sole military ally – is crucial to the country’s ability to deter such attacks. Should North Korea, for example, strike Japan, U.S. forces would be capable of rapidly delivering a devastating response. However, the deployment of North Korean nuclear ICBMs capable of striking American cities may ultimately corrode the credibility of the U.S. extended deterrent. Accordingly, as North Korea accelerates its nuclear and missile programs, Japanese leaders may begin to question the continued reliability of the U.S. nuclear umbrella, intensifying debate in Tokyo about the nuclear option.

The Origins of Japan’s Nuclear Option

History belies the superficial impression that Japan is somehow inherently anti-nuclear. In fact, Japan’s pursuit of nuclear weapons began in earnest during World War II, when Japan had not one, but two nuclear weapons development programs: The Imperial Japanese Navy’s Project F-Go at the Imperial University, Kyoto, and the Imperial Japanese Army’s Project Ni-Go, at the Institute for Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN), Tokyo. These projects were only scuttled by U.S. occupation forces after the war.

Following the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a major segment of the Japanese public understandably developed a deep dread of nuclear weapons. However, as the memory of World War II fades with each passing year beyond the nuclear attacks on Japan, the degree and intensity of Japanese public sensitivities toward nuclear weapons may gradually fade as well. Beneath the public anti-nuclear patina, meanwhile, Japanese policymakers have consistently kept Japan’s nuclear options open.

In 1957, scarcely a decade after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japanese Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi – grandfather of current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – said Japanese possession of nuclear weapons was allowed under Japan’s so-called “peace constitution,” provided that they were the minimum necessary for self-defense. “Contrary to the impression conveyed by the overwhelming popular sentiment in Japan against any association with nuclear weapons,” reported a declassified August 1957 State Department document, “there is mounting evidence that the conservative government in Tokyo secretly contemplates the eventual manufacture of such weapons, unless international agreements intervene.”

Following China’s first nuclear test in 1964, Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato (Kishi’s younger brother) told President Lyndon Johnson that if China had nuclear weapons, Japan needed them as well. Sato’s Japan Defense Agency Director (and future Prime Minister) Yasuhiro Nakasone commissioned a white paper concluding that the possession of small-yield nuclear weapons for defensive purposes would not violate Japan’s constitution.

The Johnson Administration, concerned about a possible Japanese nuclear break-out, pressured Japan to adhere to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Responding in 1967 to internal and external political pressures, Sato announced Japan’s Three Non-Nuclear Principles: Japan would not manufacture, possess, or permit the introduction of nuclear weapons in Japan. However, the Japanese Government continued to adhere to an early 1960s arrangement with the U.S. allowing U.S. warships with nuclear weapons to make calls in Japanese ports. Sato also made clear, soon after, that the Three Non-Nuclear Principles would pertain only if Japan could rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Japan finally did sign the NPT in 1970, but only ratified it six years later, in 1976 – and then, only after the U.S. reassured Tokyo that it would not interfere with Japan’s pursuit of independent nuclear reprocessing capabilities, the nuclear hedge.

Kishi’s basic policy line has been reaffirmed in numerous Japanese Government studies and fora ever since – including in 2006 by Prime Minister Abe – generally with the caveat that Japan need not pursue the nuclear option while it can rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Given the Japanese Government’s willingness to consider the nuclear option so soon after the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it should come as no surprise that, over 70 years later, Japan’s policy debate about nuclear weapons has grown more robust. North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006 seems to have accelerated this trend.

Japan’s public advocacy of nuclear disarmament continues to contrast with its support of the U.S. extended deterrent and preservation of Japan’s nuclear option. Recently, UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs Izumi Nakamitsu chaired the ceremony opening the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons for signature, even as the Japanese Government declared that it would never sign such a treaty.

A Turn of the Screw

Given its policy of preserving a latent nuclear option, it follows that Japan is the only non-nuclear weapons state with complete nuclear fuel-cycle technologies – with enrichment as well as reprocessing. As early as 1956, Japan had established the goal of developing a completely independent closed fuel cycle through the recycling of spent fuel. Several years ago, Japan reportedly had 9 tons of plutonium, enough for over 1,000 nuclear warheads, and an additional 35 tons of plutonium stored in Europe.

Japan’s world-class space launch program has led to a broad consensus that it is within Japan’s capability to produce delivery systems that could strike North Korea (although there has been no suggestion that the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency is researching ballistic missile applications for military use). The distance between Japan and North Korea is around 650 miles, while the maximum range of Japan’s missiles is currently less than 200 miles. Notably, Japanese Minister of Defense Itsunori Onodera recently requested substantial funding for research and development of high-speed missiles with extended range, with an eye toward a conventional response to the North Korean threat.

The daunting political and technical obstacles to Japan going nuclear should not be underestimated and have been described elsewhere. That said, open literature suggests that it could take between one and five years for Japan to build nuclear weapons, with the median estimate at around one or two years. It is worth recalling how rapidly the U.S. was able to produce nuclear weapons with the technologies available 70 years ago, and to consider the possibilities resulting from a modern-day Japanese Manhattan Project should Tokyo be driven to extremes.

North Korean ICBMs capable of targeting U.S, cities would be a game changer. Washington should take every reasonable measure to thwart and deter North Korea from producing and deploying them, and to counter the North Korean threat. Additionally, the U.S. should intensify its communications with Japan at every level, including through public diplomacy, with regard to strategic stability and the reliability of the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The shifting correlation of forces in Asia will have an impact on the nuclear debate in Japan, and the U.S. cannot afford to be complacent. Rather, Washington must proactively engage the Japanese with countervailing arguments to reassure them that the seamless web of deterrence linking U.S. and Japanese security will be maintained, and that the alliance is secure no matter what.