Within a week North Korea has gone beyond its New Year’s Day promise that it was close to testing an ICBM (Intercontinental Ballistic Missile), claiming it can launch one “anytime and anywhere.” This is unwelcome news for South Korea, which finds itself in a period of internal political turmoil. The impeachment of President Park Geun Hye has suspended her powers as president and calls into question how effective Seoul will be in managing its foreign policy until either Park is cleared of charges and returns to office or a new president is elected.

North Korea’s nuclear ambition is not the only foreign policy challenge South Korea faces in this leadership vacuum. Its most important bilateral relationships—with China, Japan, and the United States— are all under strain of some kind. However, South Korea is no stranger to precarious geopolitical circumstances, and its history has given it a wealth of experience in dealing with trying times.

Modern day South Korea, and the Korean kingdoms that predated it, have always been at a geographical disadvantage. Stuck between larger, more powerful neighbors, Korea’s foreign policy has always been a balancing act involving a powerful ally (long ago it was Imperial China, today it is the United States) and deft management of other regional partnerships. Today, this perpetual squeeze of competing foreign policy priorities is known in South Korea as the “Sandwich Situation.”

Until a ruling for President Park is reached, the caretaker government in Seoul will have to defer as many issues as it can. James Kim, Director of the Asan Institute’s Washington office, told The Cipher Brief that “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is reportedly keeping the first six months of the 2017 calendar year entirely blank.” Seoul may be at a serious disadvantage temporarily, but its past experience should allow it to bounce back when normal leadership returns. In the meantime, there are several regional issues unfolding that affect South Korea directly and will be priorities for whomever the president is.

South Korea’s relationship with its northern neighbor is the most pressing and worrisome. Even before the impeachment and subsequent leadership vacuum, North Korea had demonstrated advances in its nuclear and missile programs over the course of 2016. Since the impeachment, Pyongyang has not carried out any provocative acts and has only released provocative statements. A South Korean Minister of Defense spokesman announced that an ICBM test would be met with stronger sanctions. However, in the event of a provocative act, sanctions would come through the UN security council, and South Korea’s role as a stakeholder in determining sanctions could be diminished by its leadership situation.

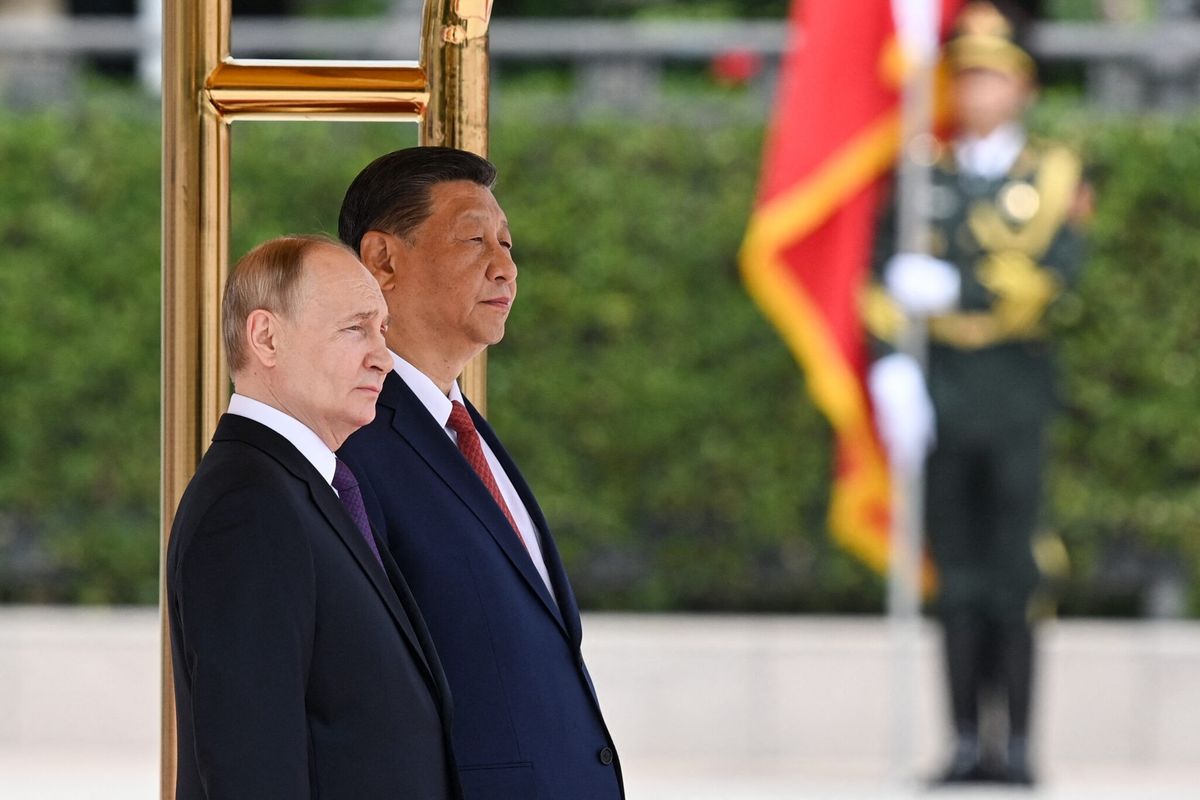

China is dialing up the pressure in response to South Korea’s decision to deploy the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) missile defense system by restricting South Korean exports—namely cosmetics and K-Pop music. China’s ranking as South Korea’s top destination for exports means it can dial up even more pressure if it wishes. Additionally, a rocky start to a Sino-U.S. relationship under President Trump could have additional ramifications for South Korea if it is forced to pick sides.

Two important agreements with Japan, involving reparations for wartime atrocities committed by Japan during World War II and an intelligence sharing agreement, face domestic opposition as they are tied to the unpopular legacy of the Park administration. Overturning one or both of these agreements would be a major setback at a highpoint in good relations between Seoul and Tokyo.

In its most important bilateral relationship with the United States, South Korea’s leadership vacuum comes at a bad time. When Donald Trump becomes president, he will have no counterpart in South Korea with which to establish a rapport and set the course for the future of the U.S.-ROK alliance. This could affect responses to regional issues in the near term, such as further North Korean provocations. Scott Snyder, Senior Fellow for Korean Studies at the Council of Foreign Relations told The Cipher Brief, “Seoul will be disproportionately affected by how the new president handles the next widely-expected provocation from North Korea, whether it be an ICBM launch, a sixth nuclear test, or something in between.” Without unified leadership, Seoul may have trouble delivering a cohesive response, and therefore cede a stronger role to Washington.

Without long term leadership, South Korea is at the mercy of regional events. When the dust settles and Seoul has permanent leadership once more, how these events transpired in the interim will determine how much catching up the new administration will need to undertake. With a wealth of experience in navigating difficult diplomatic circumstances, South Korea will likely make the most of the hand it is dealt - as it always has.

Will Edwards is an international producer at The Cipher Brief. Follow him on Twitter @_wedwards.