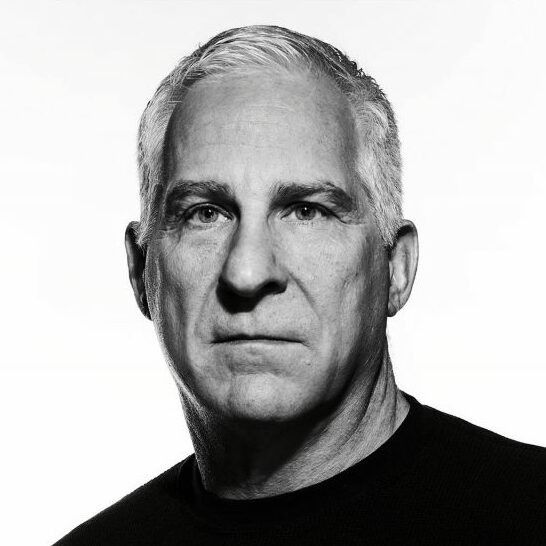

Last month, our Network weighed in on the situation in Syria, making the case for increased American involvement in the conflict. One of our contributors, Rob Dannenberg, a former head of security for Goldman Sachs, explained Putin’s decision to intervene in Syria. This month, we pick up that conversation with John Sipher, a former member of CIA’s Senior Intelligence Service. Sipher offered his take on Putin, concluding the only way to deter Russian aggression is to stand up to it.

As a father of three boys, one of my favorite shows is “Malcolm in the Middle,” a 2000-2006 sitcom about a dysfunctional family of six. The middle son, Reese, is a delinquent bully who spends all of his time devising fiendish plans to sow mayhem and violence. When he finally falls for a girl in school, the only way that he knows how to show affection is by torturing her.

I’m convinced that the best way to assess Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recent foray into Syria is less to search for his overarching geopolitical or strategic rationale than to see him as a simple schoolyard bully. Like Reese, his actions in Syria and elsewhere can be read as much as a boorish attempt to get attention as anything more high-minded.

The notion of Putin as a bully is not a new one, but anyone who has lived in Russia or spent time driving in Moscow traffic is familiar with the behavior. The loutish personality is a mixture of a post-Soviet inferiority complex and long-established Russian behavioral traits.

Putin grew up as a pint-sized, unimpressive youth in a nasty post-war Soviet apartment block in Leningrad chasing rats around the hallways (having lived in a “nice” Soviet block, I can attest that even the decent buildings were dark, crumbling and smelled like urine). Putin himself brags of his thuggish youth, boasting about his many fistfights. He eventually was able to land his dream job in the KGB, but was shuffled off to the JV team, engaged in secret police work tracking dissidents rather than joining the elite foreign intelligence cadre.

When the Soviet Union fell he was working as a low-ranking officer and eventually hooked up with political figures in his home town. Through a unique series of coincidences and relationships, he was in the right place at the right time several years later when an increasingly drunken and incoherent Boris Yeltsin was appointing and firing potential successors, looking for someone who wouldn’t prosecute him and his cronies. Putin was the gray man who could be be counted on to keep the secrets of Yeltsin’s “family.”

When he took over as the appointed President of Russia, Putin had the background of a mid-level bureaucrat in a new, diminished, and impoverished country trying to rebuild from the fall of the Soviet state.

Psychologists tell us that the root of bullying is an inferiority complex, with a strong sense of envy. Can you imagine the massive sense of inadequacy that would accompany a promotion from being a relatively unknown middling bureaucrat to the being a dictator of a failed State? Being anointed as President of a nuclear power from such a precarious position must have been an emotional and psychological shock. On one hand, your ego is stroked and inflated, and on the other the reality of your background must insure a fragile psyche.

Who knows?

One thing that is clear, however, is that Putin went on the offensive. He blamed the U.S. for the weakened state of his country and consistently pursued almost any policy that could be expected to hurt or anger the U.S. His sense of grievance led him to see slights in almost every U.S. move. Anything that hurt the U.S. was a plus for Russia.

This belief, that U.S. – Russia relations are a zero sum game, and that any loss for the U.S. is a gain for Russia, has been on display these past few weeks. When Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was recently asked which of the two governments in Libya the Russians will support, he answered “whichever one the U.S. is against.”

Western Kremlinologists recorded a similar pattern in Moscow’s actions during the Cold War. It often seemed that the Soviets provoked the West in order to satisfy a craving for attention of any variety – positive or negative. If they couldn’t get credit for building a decent automobile or useful computer, at least they could spur a response from the West by deploying missiles or voting against western initiatives at the UN. It was okay to be despised but never ignored.

This behavior is not only Soviet but is also very “Russian.” Marvin Kalb’s new book, Imperial Gamble, is an effort to explain Putin’s actions in Crimea and elsewhere as a natural extension of Russian history and the Russian personality. Anyone who has lived in Russia has certainly witnessed this type of boorish and aggressive behavior.

I cannot adequately describe the level of obnoxious and aggressive behavior of Russians drivers on the streets of Moscow. If U.S. drivers were half as rude as the average Russian driver, road rage would be our number one cause of death. Russians pass on the sidewalk, drive through parks, speed down oncoming lanes, and cut off other cars in the most dangerous ways imaginable. Feel free to Google videos of Russian traffic.

Likewise, Russians view every civic relationship outside the family with an element of distrust and every interaction as a power struggle. No matter if the woman who works in the bread store is on the lowest wrung of society, when she is in a position of power behind the counter, she will consistently wield her position like a weapon. At some point, most westerners living in Moscow will find themselves dumbfounded when they are physically bowled over by an elderly lady aggressively pushing her way into a queue.

When Americans are faced with this kind of in-your-face loutish behavior, they are shocked and surprised, even paralyzed. It doesn’t seem to have a purpose but is just bullying for the sake of bullying. Similarly, Putin’s actions in Georgia, Crimea, Ukraine, Syria, and elsewhere continue to surprise us. If you have a temporary power advantage, use it, even if it doesn’t seem to have a purpose.

I’m not a psychologist, but I suspect that years of living in a police state has left civic discourse in Russia in a state of disarray. Real trust is relegated to a small circle of family or friends. Outsiders are enemies. Indeed, Russians are so good at spying because they naturally compartmentalize their relationships, instinctively hold information within small cells of trusted friends, and are comfortable lying to outsiders.

So what does it mean?

While we debate Putin’s goals in Syria and elsewhere, we should certainly weigh all the possibilities, provide for contingencies and calculate the balance of power. However, we should also keep in mind that he is a special kind of bully. A Russian bully. He is like Reese in “Malcolm in the Middle.” He just can’t help himself. He wants attention, no matter how he gets it and may not have any real end goal other than to be “relevant.” If it bothers us, that is enough of a reason to take action.

While I’m skating on thinner ice here, my time on the streets of Russia also provides me with a possible remedy to this type of bullying. From my experience, when you eventually stand your ground and make clear your boundaries in the face of Russian assaults, the Russians will always back down. Standing up to a bully is the only way to stop him from pushing forward. (I contrast this to my time in Serbia, where the Serbs will always escalate even if it is not in their interest – but this is a story for another time).

I’m not one to constantly push for muscular American action overseas or offer simplistic platitudes to describe complicated issues. However, when we are dealing with a bully who knows that he doesn’t have the strength to back up his actions, it is worth drawing a line in the sand. Russia is a weak country with few friends but also one willing to take brazen action—a bully.