Bottom Line: As monsoon season bears down on Southeast Asia, U.S. officials say up to a 100,000 Rohingya refugees sheltering in the hills of Bangladesh face a potential humanitarian catastrophe. They are among the 860,000 ethnic Rohingya Muslims driven out of Myanmar by a violent crackdown that the U.S. has called a campaign of ethnic cleansing. But the plan to return them home is slated to take two years – and they don’t want to go, nor do their former Buddhist neighbors in Rakhine State want them. The standoff could spell further radicalization of the Rohingya, swelling the ranks of what is now a relatively small rebel movement inside Myanmar, and leading to further armed conflict and refugee flight.

Background: Oppression of the ethnic Rohingya by the people and government of Myanmar is deeply rooted in the belief that Rohingyas are illegal immigrants from the Indian state of Bengal, with no place in mostly Buddhist Myanmar. The country’s nascent transition to democracy has not improved the Rohingyas’ lot as they remain without basic legal rights.

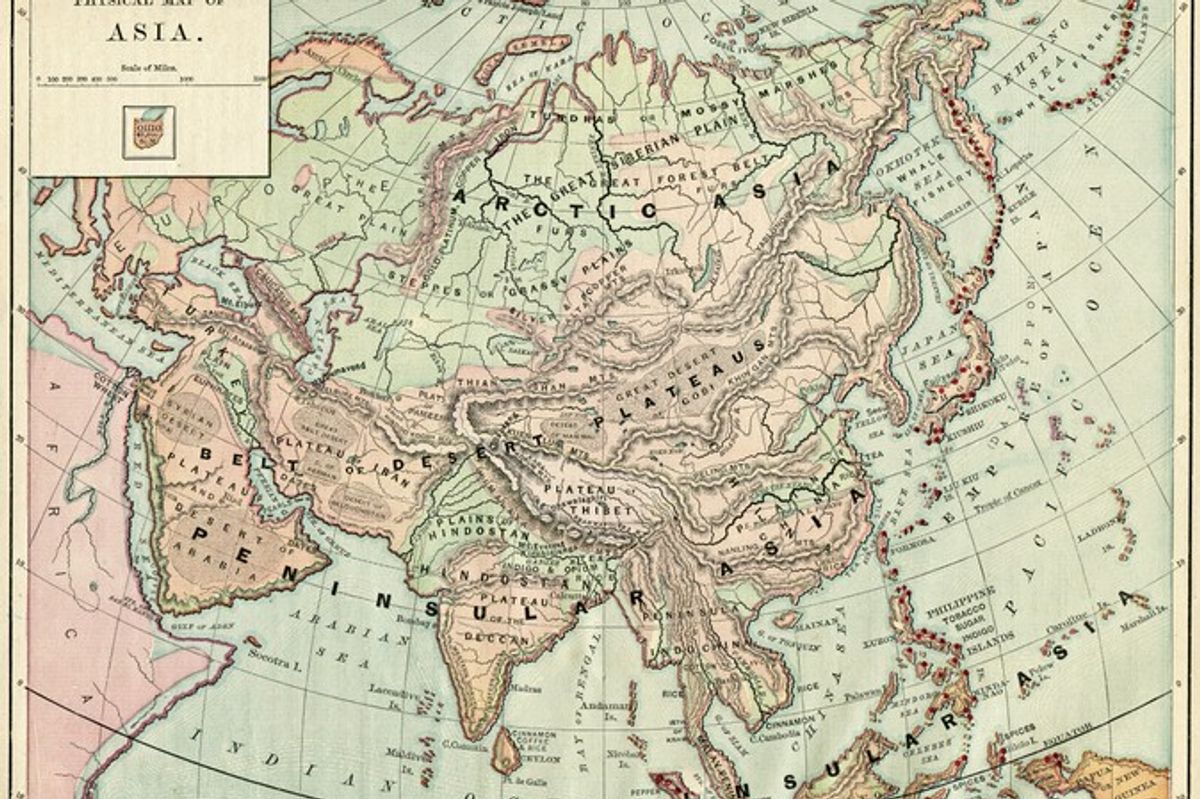

- Since gaining its independence in 1948, Burma—now known as Myanmar—has struggled with ethnic strife. Ethnic Burmese form about two-thirds of the population, with the remaining third divided between over a hundred other groups. From 1962 until 2011, Myanmar was ruled by a military junta known for vast human rights abuses and suppression of popular protests, in response to which the United States imposed sanctions in 1990.

- In 2011, the ruling junta officially dissolved established a civilian parliament and president, though under a constitution ratified in 2008, the state’s military retains control of 25 percent of the seats in parliament. In addition to implementing widespread economic reforms and amnesty for most political prisoners, the government initiated a nationwide peace process with ethnic rebel groups that continues to make progress.

- The estimated one million individuals that comprise Myanmar’s Rohingya minority predominantly practice Islam and are ethnically and linguistically distinct from the Buddhist groups that dominate the country. The Myanmar government maintains that the Rohingya are illegal Bengali immigrants, refusing to recognize them as a valid ethnic group. In 1982, the military junta stripped the Rohingya of citizenship, and rights groups have reported government restrictions on freedom of movement, marriage, family planning, employment, and many other elements of life.

- In 2012, large-scale violence erupted between the Rohingya and Arakanese Buddhists, both living in Myanmar’s western Rakhine state, which the World Bank estimated in 2016 to have a poverty rate of 78 percent, more than double the country’s national average. Rights groups maintain that violence in the region has been overwhelmingly one-sided, with the Rohingya as victims; state security forces are guilty of a wide range of crimes against the minority; and local political officials and Buddhist monks have participated in inciting local Arakan Buddhists to violence.

- In August 2017, a Rohingya militant group known as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, or ARSA, attacked 30 local police posts with improvised bombs and small weapons, killing 10 police officers and losing 59 of their own. The Myanmar military responded to the attack—the first of its kind—with overwhelming force, burning hundreds of villages, killing over 6,700 Rohingya and prompting more than 650,000 individuals to flee over the Bangladesh border within four months. Today, more than 860,000 Rohingya live in makeshift camps near Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, with no immediate prospects for safe return—and for many, no home left to return to.

Alasdair Gordon, former senior Australian national security official

“The push by Buddhist-dominated Myanmar, particularly the Myanmar military, to cleanse Burma of these ‘damn Muslims,’ and their anger with what they call ‘Bengalis’ because they don’t recognize them as Burmese citizens, is just disgraceful.”

Amb. Derek Mitchell, former U.S. Ambassador to Burma

“In 2012, over a hundred thousand Rohingya were placed in pens where they were barely able to move or have a livelihood, let alone enjoy basic citizenship rights. This went on for five years. And we warned the government that these are the conditions that could lead to radicalism; you’re giving people no hope and no future. But for five years, nothing happened. And that’s because the Rohingya simply aren’t oriented towards radicalism, despite the violent actions of a few.”

Issue: The displacement of the Rohingya across the border into Bangladesh has caused significant strain on Bangladesh’s economy and has engulfed the international community with yet another evolving humanitarian crisis. Now, monsoon season is about to begin in Southeast Asia, threatening to pummel the displaced population and possibly lead to large-scale loss of life, embittering the Rohingya population further.

- In the coming months, the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, estimates that more than 100,000 Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar will be threatened by landslides and floods. A senior U.S. administration official who recently visited the camps told reporters that the same number of people “face imminent danger,” as many of their structures are “literally built on hills, [and] many people are going to have to be moved.”

- Longer-term, there isn’t a clear path to resolving the displacement of the Rohingya people. In January, Bangladesh and Myanmar signed an agreement to complete their return within two years, but conditions do not exist for the hundreds of thousands of migrants—forcibly displaced by what top UN officials have referred to as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”—to safely and voluntarily return to their homes, many of which no longer exist. Locals in Rakhine State have told the government they are opposed to refugees being resettled in their communities.

- The population of Myanmar at large does not sympathize with the plight of the Rohingya, due in large part to rapidly growing Buddhist nationalist movements—combined with existing economic problems and, as noted by UN investigators, the power of social media in spreading hate speech.

- The emergence of the militant group ARSA, which says it fights to end the oppression of the Rohingya people, stokes concern that large-scale radicalization could occur within the population, undergirded by bleak prospects for a resolution to the conflict and deep mistrust of the Myanmar government. ARSA claimed responsibility for another attack in Rakhine State in January in which a military truck was ambushed and five members of the security forces wounded.

Joshua Kurlantzick, Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia, Council on Foreign Relations

“A large percentage of people in Myanmar really don’t care or are uninterested in the crisis in Rakhine State, and don’t really have much sympathy for the Rohingya. The military also retains significant power over the security situation, key security ministries and over politics itself. But that doesn’t mean that Suu Kyi couldn’t have been a leader and tried to change people’s minds, so despite these obstacles, she’s still complicit in massive human rights violations.”

Amb. Derek Mitchell, former U.S. Ambassador to Burma

“The domestic climate [in Myanmar] is overwhelmingly against the Rohingya. It’s been drummed into citizens’ heads that the Rohingya are a threat to the security of the country, that they’re not part of the national fabric of the country. So when the ARSA attack happened, it just reaffirmed all the concerns and insecurities that people had about this population, and therefore the response by the military was generally viewed as a necessary thing for national security.”

Response: In January, Myanmar and Bangladesh struck an agreement to complete a return of the Rohingya people back across the border within two years, but it seems unlikely that conditions will exist in which a safe, voluntary repatriation will take place. The presence of more than 860,000 refugees places a strain on the country’s already-overburdened infrastructure, but no regional actors have proved willing to either assist in large-scale resettlement or put pressure on Myanmar to change course.

- The international community continues to press Myanmar to end its oppression of the Rohingya people and respect their human rights, but the government has so far failed to change course. De-facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi has been roundly criticized for her inaction toward the plight of the Rohingya, even facing calls that she be stripped of her 1991 Nobel Peace Prize for nonviolent resistance of the military junta. But she’s refused to acknowledge her government’s role in a campaign of ethnic cleansing, likely in part because of rising Buddhist nationalism throughout the country, and her tenuous influence on the still-ascendant Myanmar military.

- The Myanmar military continues to deny charges of crimes against humanity, ranging from sexual assaults to systematic ethnic cleansing, instead maintaining it carried out a legitimate counter-insurgency operation. As stated by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, “A huge effort of reconciliation is needed to allow [repatriation] to take place properly.” The UNHCR was not invited to take part in the agreement reached by Myanmar and Bangladesh.

- Despite the humanitarian cost, the re-imposition of broad sanctions lifted from Myanmar by President Barack Obama in 2016 would likely cause more harm than good, resulting in less leverage and popular support for the United States, while also serving to undermine the country’s ongoing democratic transition by undoing economic progress.

Jonah Blank, Senior Political Scientist, RAND Corporation

“The Rohingya refugees have good reason to distrust the government of Myanmar: This regime drove them into exile, has perpetrated violence against them that the UN has classified as ethnic cleansing, and even now refuses to acknowledge them as citizens—despite the fact that most Rohingya have lived in Myanmar longer than the post-colonial nation has even existed. Without firm guarantees, backed up by the international community—they are quite right to resist a return to Myanmar.”

Amb. Derek Mitchell, former U.S. Ambassador to Burma

“Thoughtful, strategic sanctions that are very targeted, rather than broad-based sanctions, may be a reasonable approach to consider, for example on military individuals and companies. But I don’t think that the re-imposition of broad U.S. sanctions would help us help the Rohingya, and they’re certainly not going to help reform efforts inside the country.”

Looking Ahead: There are no easy answers to the crisis faced by the Rohingya, and reason to believe the security threat posed by groups like ARSA—which is currently low—is likely to get worse. Within Myanmar there is no appetite for acceptance of the Rohingya as a legitimate ethnic group, let alone serious reconciliation and reconstruction of livelihood. Within the international community, there seems to be no appetite for enacting the targeted sanctions that might shift the Myanmar government – or military’s – behavior.

Joshua Kurlantzick, Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia, Council on Foreign Relations

“The actors that would be most influential in this situation would be regional—China, Japan, India, Thailand, Singapore—but I don’t know that any of those actors are going to do anything about the situation. There are actions that can be taken by other actors, such as targeted sanctions, the freezing of senior generals’ bank accounts, cutting off the nascent process of normalization of military-to-military ties, but the actors that have the most leverage probably aren’t going to do anything.”

Jonah Blank, Senior Political Scientist, RAND Corporation

“We’ve seen a very sudden radicalization of the majority Buddhist community in Myanmar: This has been brewing for a while, and it exploded over the past decade. We haven’t yet seen much evidence of radicalization among the Muslim Rohingya—but it is almost inevitable that it will occur. Oppression breeds extremism, and long-term refugee populations are particularly fertile breeding-grounds for violent radical groups. Global terrorist groups such as ISIS and Al Qaeda have been using the Rohingya genocide as a recruitment tool for years. A few years from now, we may look back on this moment as a time when the world could have prevented the radicalization of one million Rohingyas—and instead decided to do nothing.”

Brian Garrett-Glaser is the content manager for The Cipher Brief.