China and North Korea were no doubt as surprised as anyone by Donald Trump’s dramatic electoral victory. They had probably anticipated that a new Clinton Administration, like the Obama Administration before it, would be anesthetized by Chinese diplomacy and continue the policy of “strategic patience”—really, strategic neglect – that had allowed the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) to continue gradually on its path towards developing ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons. They probably assumed sluggish, reluctant acquiescence to North Korea eventually deploying ICBMs capable of threatening the American people with nuclear strikes on the continental U.S. From Beijing’s perspective, while not ideal, this might bolster China’s strategic objective of deterring U.S. military action against North Korea.

However, the Trump Administration correctly scuttled “strategic patience,” and the administration now recognizes that we are at a dangerous strategic tipping point, one where the balance of forces is shifting dramatically against the United States. DPRK possession of nuclear ICBMs [intercontinental ballistic missiles] could be seen as engendering strategic decoupling of the U.S. from its regional allies, particularly Japan and the Republic of Korea. Just as former French President Charles de Gaulle questioned—during the height of the Cold War when the Soviet Union was building up its nuclear forces in Europe—whether the U.S. would be ready to trade New York for Paris, Asian leaders might doubt whether the U.S. would trade New York for Tokyo or Seoul.

The U.S. policy reversal helps explain North Korea’s sudden motivation to rush across the ICBM finish line before it can be thwarted or deterred. This in turn explains the urgent need for action by the U.S. and its allies to prevent North Korea from doing so.

By now it should be clear that – barring an agonizing reappraisal by China of its fundamental strategic interests, including preserving North Korea as a buffer state that absorbs inordinate time and attention from the U.S., Japan, and South Korea and complicates their strategic thinking — there is nothing the UN Security Council can enact in terms of sanctions against North Korea that will diminish Pyongyang’s determination to build nuclear ICBMs and target the U.S. with them. Even when the latest round of sanctions under UN Security Council resolution 2371 begins to have an effect in several months or even longer, Pyongyang’s calculus will be unaffected. This is partly why China and Russia agreed to them so easily (also as a means of fending off U.S. secondary sanctions on themselves). Given North Korea’s extreme economic dependency on China, the ball remains where it always has been, in Beijing’s court

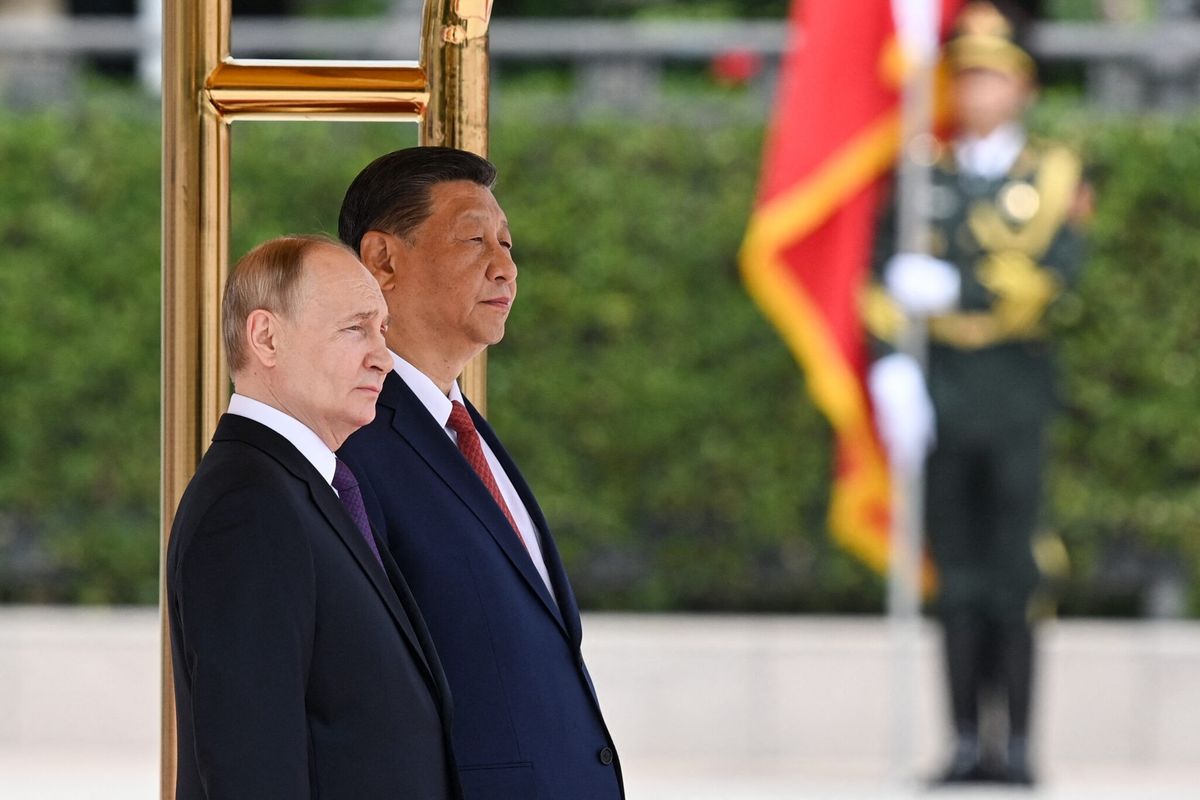

The U.S. should therefore seek to influence the debate in China as to whether North Korea is more a strategic liability than an asset in an effort to incentivize an effective Chinese clampdown on Pyongyang. The timing is propitious in the run-up to, and aftermath of, the 19th Party Congress next month; certainly President Xi will have a freer hand to act after further consolidating his position. The U.S. and its allies should, first and foremost, demonstrably raise the cost to China of its present course of action, mainly through countermeasures that respond to the North Korean strategic threat and simultaneously degrade China’s strategic posture in the region.

The U.S. menu of options includes:

- Pursue robust deployment of Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD), including Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) systems in the ROK, Japan, and the surrounding maritime environment.

- Accelerate deployment of active defense and strike capability for both the ROK and Japan, citing the North Korean threat.

- Double down on a more visible, physical U.S. “pivot to Asia” through deployment of greater U.S. naval and other military assets to the region.

- Intensify trilateral security cooperation between the ROK, Japan, and the U.S., including trilateral ballistic missile defense – with the ROK integrating its Korea Air and Missile Defense system into the broader and better allied system – as well as anti-submarine warfare and mine-clearing. Upgrade the limited General Security of Military Information Agreement between the ROK and Japan to a full-fledged version. Suggest that other regional partners might be included at a later stage and none definitively precluded (hint: Taiwan).

- Enhance and merge U.S. dialogues on strategic stability with Japan and the ROK to reassure our allies about the U.S. nuclear umbrella in a regional context. Hold annual 2+2+2 talks of foreign and defense ministers to coordinate overarching security policy, as well as a system of attendant regularized trilateral security talks at mid- and working level.

- Open talks with the ROK and Japan on a trilateral arms trade cooperation treaty – along the lines of those the U.S. signed with the UK and Australia – as a signal of intent to broaden and deepen trilateral interoperability and reduce barriers to exchanging defense goods and services.

- Use public and private diplomacy channels to explain that all these moves are to help ensure a seamless web of deterrence vis-à-vis North Korea and are not aimed at China per se; and that they are the natural consequence of China enabling North Korean nuclear and missile programs.

Vis-à-vis China, the U.S. could also:

- Continue to apply limited and carefully targeted secondary sanctions on Chinese banks and state enterprises that are enabling North Korea, with the implicit threat of more to come, in order to motivate stronger and more wide-spread action by Beijing against accounts held by North Koreans in Chinese state banks.

- The U.S. took a major, and long overdue, step in this direction on September 21 when it issued an Executive Order expanding the Treasury Department’s authority to target for sanctions those individuals, companies, and financial institutions involved in business with North Korea.

- According to a Senior Administration official, under the Executive Order, financial institutions, including Chinese banks, will be directly exposed, as well as indirectly exposed with regard to commercial entities to which they have ties. If commercial entities are sanctioned for North Korea-related trade, financial institutions doing business with them will need to sever ties to them immediately to avoid being caught up in sanctions themselves. The official said that, while banks and commercial entities may adjust their activities in reaction to the Executive Order itself, no one is under the illusion that this will be sufficient, and we can expect specific designations going forward.

- Banks relying on U.S. dollars to conduct business would be vulnerable to U.S. regulators, but smaller Chinese banks working primarily with North Korean clients might not be adversely affected. That said, the implicit threat of escalating to a cut-off of some major Chinese banks from the U.S. financial system is compelling. A report by the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) includes a blueprint for possible action on secondary sanctions

And in the aftermath of the 19th Party Congress, the U.S. should approach China at the highest level to:

- Foreshadow for Beijing how the North Korean threat is leading inexorably to the transformation of northeast Asia into a highly militarized region. This will be a direct response to the North Korean threat, but it will also greatly degrade China’s relative strategic position.

- Remind Beijing that assurances by Tokyo and Seoul not to pursue nuclear weapons have always been predicated on their clear, unambiguous reliance on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, which risks being corroded by North Korean ICBMs.

- Propose top-level bilateral U.S.-China talks on North Korea. Make clear that the immediate U.S. objective is to reach an agreement with China to apply all available means to bring North Korea to heel. In the short term, this would include coercing North Korea into a moratorium on missile and nuclear tests with an iron-clad verification regime. We must make clear that we are not interested in process – e.g. the application of particular sanctions – we are interested in results.

- These talks would include contingency planning for the case of DPRK collapse. The Chinese have been reluctant to participate in stand-alone contingency planning talks for fear of triggering (more) paranoia in Pyongyang, but might acquiesce if we agree to hold them on the margins of broader discussions and keep them secret. Just the fact that we propose holding them will signal to Beijing that we believe DPRK collapse is a relatively near-term possibility.

- Discussion should also include mutual reassurance about strategic intentions in the Korean Peninsula. In this context, we should emphasize that the future of a reunified Korea is up to the Korean people, and that while U.S. preference is frankly for the continuation of our military alliance with the Republic of Korea, understandings concerning future U.S. military deployments in a reunified Korea could be discussed.

Taken collectively, these steps would have powerful intrinsic value in bolstering the U.S. and allied strategic position in the face of North Korean efforts to deploy nuclear-tipped ICBMs and alter the strategic nuclear balance. They might also strengthen the hand of those in Beijing arguing that North Korea is more a strategic liability than an asset, and that a fundamental shift in China’s approach toward North Korea is overdue.