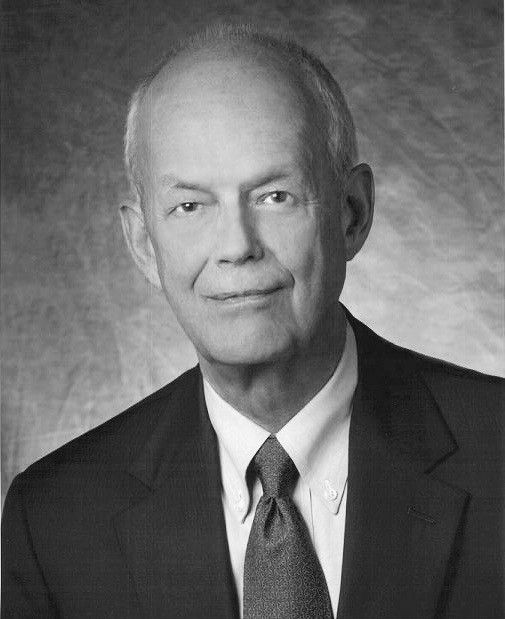

It was just after lunchtime on April 18, 1983, when a suicide bomber attacked the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon. 63 people were killed and the shocking nature of the attack prompted the U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz to order an evaluation of the State Department’s security posture overseas. He asked Admiral Bobby Ray Inman (Ret.) to take on the task.

The ‘Inman Report’ as it became known, made a series of recommendations to shore up America’s diplomatic exposure overseas.

The Cipher Brief caught up with Admiral Inman to ask about lessons learned then and what we now know, three years after Benghazi. This edited interview gets right to the point.

The Cipher Brief: Admiral, you and your team offered a number of key recommendations that set minimum security standards in order to protect U.S. Embassies around the world, and that was 30 years ago. What did you learn back then and how do those standards apply today?

ADM Bobby Inman: Back in 1985, we created very tough standards for U.S. embassies and consulates around the world. The buildings had to be free standing, they had to be defendable, new Embassies and consulates had to be built 75 feet back from the street so you were much less vulnerable to truck bombs and car bombs, and we had to make sure that they were not susceptible to penetration by host governments, which had happened in some countries. We realized that you couldn’t protect employees coming to and from work, there it was more about providing alarm systems, things like that, but the key issue was that these people were representing us abroad, but they should not be risking their lives at the workplace. Complicating it though, was that people had to be able to get out of the buildings to meet people where they were so they could go out and meet with people and make their observations and come back and report.

TCB: Some of the recommendations you made also addressed issues of accountability?

BI: If there was a loss of life, you had to identify lines of accountability and assign responsibility for it. 78 of the 81 measures we recommended were approved and we were told to stay with it until we got Congressional authority. Based on advice from the Secret Service, we had recommended upgrade of the quality of the professional advice on security available to Ambassadors and to the State Department. As some of the measures were implemented, they began to show improvements in Embassy security in the Middle East and Europe.

TCB: Those measures seemed pretty effective until the nature of the threat began to change, no?

BI: Yes. Now fast forward to Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. The adversaries looked and saw that other embassies weren’t as well protected, so they attacked them with a large loss of life. Now, we had the requirement for an accountability board and after they met, I was called and told that the recommendations made in our report were still solid, they just hadn’t been implemented.

Those events had led to the development of an office to manage the building of new embassies and there was a substantial amount of money put into that, but what happened is that we went for a few years when nothing happened, and as a result, money that had been set aside started to be shifted to other projects.

TCB: So the threat had already changed, and then it changed again in Iraq for the U.S. State Department?

BI: Years later in Iraq, there was the added need to send out mobile teams with State and Defense representatives and suddenly there were requests for waivers to the security process. Waivers allowed for the building of temporary facilities, the argument was that these aren’t embassies or consulates, they are essentially temporary, and Congress was informed, so there were no surprises, but it was a deviation from the original recommendations.

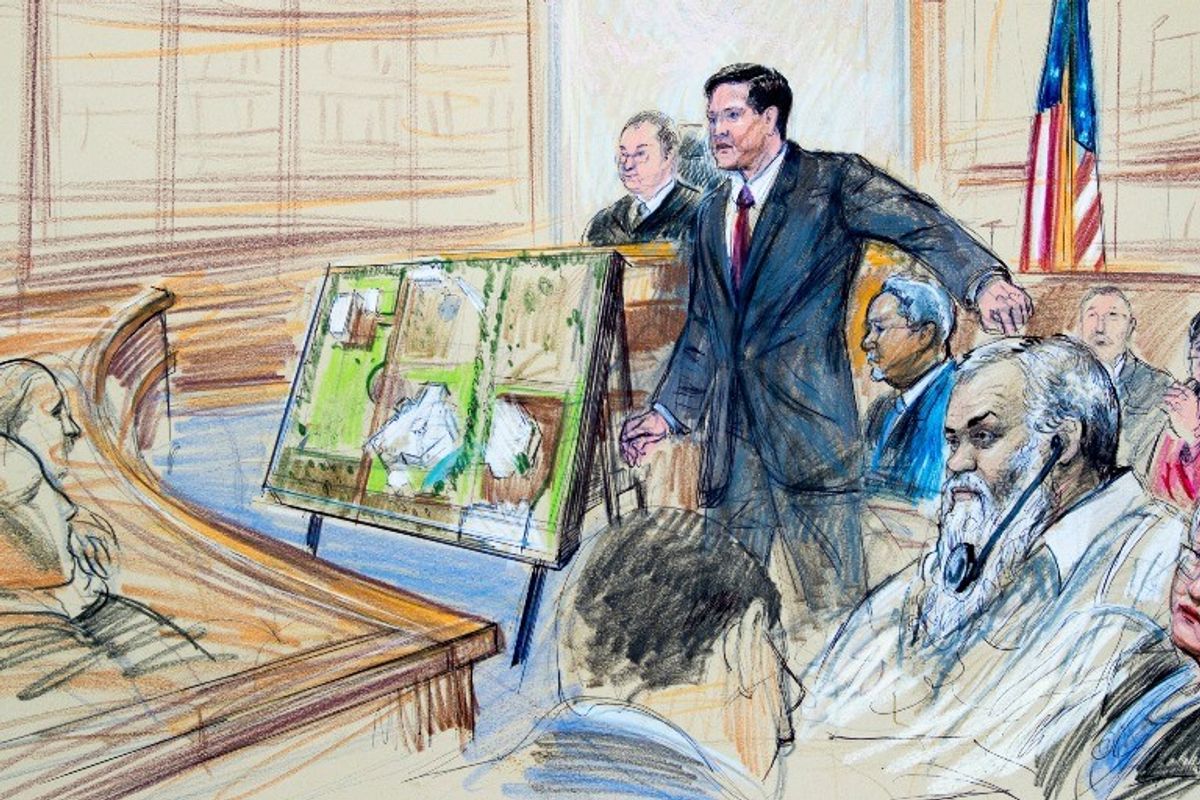

Now fast forward to the revolution in Libya. Qaddafi falls. When Secretary Clinton was getting ready to go out for her first visit, they had reopened the Embassy, but they did not have a residence for the ambassador. The security team that went out to reopen the embassy, also looked at Benghazi and reported back that it was un-defendable, and that it should either be upgraded to meet standards or closed.

TCB: What about the significant shift in 2003 by the State Department to using contractors to provide security instead of U.S. Marines? How did that impact security efforts?

BI: I spent some time with former Secretary George Schultz two summers ago and he told me that his only regret was that the State Department didn’t staff up to provide the level of security needed using in house employees and that they had to use private security contractors to get to the security level envisioned. There were opposing views from the current Undersecretary for Management Patrick Kennedy. If you hire the people on staff, you absorb retirement and health care costs.

From the beginning, career State servants were always afraid that they were ultimately going to have the cost of all of this taken out of their budget and that might impact future opportunities to conduct state affairs and things like that.

TCB: How has the nature of the threat changed?

BI: In 1983, the Iranians were suspected of funding Hezbollah to carry out the attack on the Embassy, but now you have non-states, terrorist groups who have been the prime threat. Al Qaeda in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, this latest attack in Benghazi, so from the beginning the concern has been about non-state actors but funded by states. The threat has been there for 30 years, but now its more diverse since bin Laden’s death. Al Qaeda didn’t go away, it metastasized and now you look at al Shabaab, Boko Haram, to the number of groups pledging loyalty to ISIS so if anything, the nature of the threat has not basically changed but the players who may execute on the threat are far more dispersed.

TCB: In your mind, Admiral, what are the three key lessons learned from the Benghazi attack?

BI: First, we need holdfast to recommendations. If you cannot defend, then close. Don’t leave people sitting there, exposed. People assigned to embassies need to be constantly aware of their security environment and its hard to stay out there on the point all the time if you don’t visibly see the threat, nonetheless, individual awareness and constant focus on the concerns is critical.

Second, there can be no slack in the intelligence efforts to try and identify and prevent threats rather than deal with them after the fact. That speaks to what is the level of effort? Human Intelligence? Signals Intelligence? We need to be able to identify the threat and understand their goals. It’s a very tough job.

Finally, what are we going to do as a country in response to an attack? Do we look the other way? The application of force cannot be just a threat. We knew in 1983 who funded the attack on the Marine barracks, we knew who ordered an attack earlier that year on the Embassy and our response was to withdraw. Our enemies have clearly demonstrated that they are willing to deliver a blow. We need to be ready to respond appropriately.