Bottom Line: Since 2016, the North Korean regime has shown its hand as a state sponsor of cybercrime by targeting international financial institutions, engaging in broad ransomware campaigns, and illegally accruing and laundering cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. This pattern of behavior supports Pyongyang’s objective of self-financing the ruling Korean Worker’s Party (KWP) and the Korean People’s Army (KPA), including bankrolling its nuclear and ballistic missile development. Through direct engagement in global illicit activity, the regime of Kim Jong Un is seeking to circumvent international sanctions and sustain its continued despotic rule over the people of North Korea.

Background: Unlike other regions of the world such as Latin America or Eastern Europe, where organized crime attempts to penetrate and corrupt the state, the North Korean state proactively collaborates with organized crime on a global scale. Pyongyang uses its diplomatic outposts, military vessels and a web of front companies and complicit international financial institutions to trade in weapons, drugs and counterfeit foreign currency.

- Since around 1974, North Korea’s model of “criminal sovereignty” has been orchestrated out of Central Committee Bureau 39, also known as Office 39. Initially, it was a way for diplomatic missions to finance their operations on behalf of a cash-strapped Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). After the collapse of its primary benefactor, the Soviet Union, in 1991, Office 39 quickly became a centerpiece of Pyongyang’s financing. In November 2010, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Korea Daesong Bank and Korea Daesong General Trading Corporation for being “owned or controlled” by Office 39.

- In the late 1990s, Pyongyang’s drug trade switched from opium to methamphetamines, as counterfeit pharmaceutical labs were revamped to manufacture the synthetic drug, referred to locally as “ice.” The narcotic would then enter international markets via North Korean diplomatic outposts in Southeast Asia that were cooperating with local criminal syndicates. In November 2013, the U.S. Justice Department unsealed indictments for five individuals for conspiring to transport 100 kilograms of North Korean meth – at $60,000 a kilogram – from Thailand to the United States.

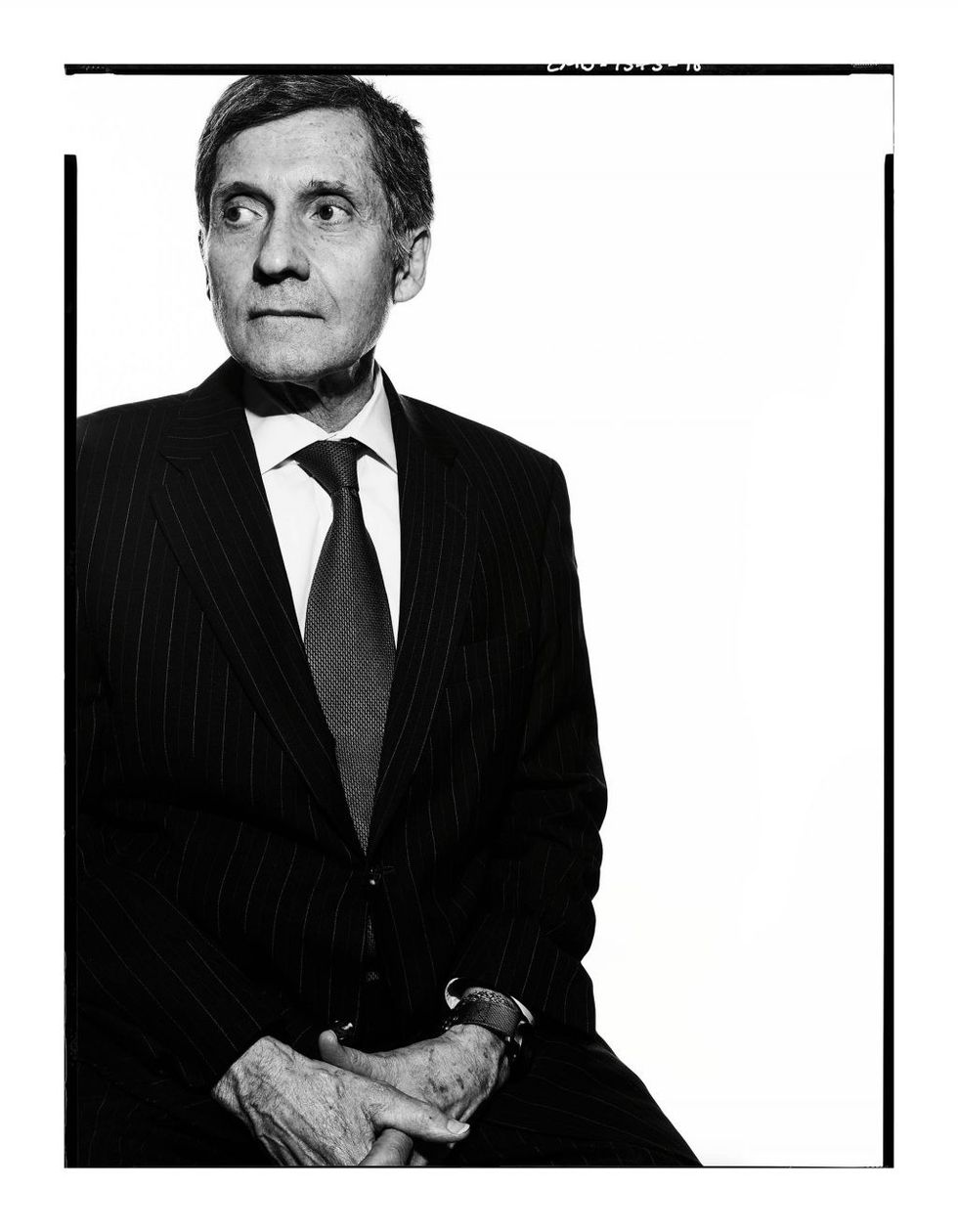

Amb. Joseph DeTrani, former Director of East Asia Operations, CIA

“North Korea has always been in the illicit/criminal business, mainly for money. They sell missiles and missile technology for the money, with the added benefit of selling these missiles to states at war with the U.S. and its allies, i.e. Iran, Libya and Syria. They counterfeit our $100 note for the money. Ditto for their counterfeiting of pharmaceuticals, cigarettes and the sale of meth and other narcotics. It's these criminal transactions that have provided hundreds of millions of dollars to Pyongyang, to support the nuclear and missile programs and support a lavish life style for the Kim family and the loyal elites. As North Korea is being denied the ability to sell missiles to other rogue states, due to the Proliferation Security Initiative and sanctions enforcement; and as we put more security features into our new $100 note, and as we closely monitor their diplomats and others to prevent them from trafficking in drugs, cigarettes and pharmaceuticals, North Korea is transitioning more to cybercrime—for financial gain. In fact, this is and will be the most lucrative illicit activity available to North Korea. And it's a twofer—money and disruption/espionage.”

Issue: With the maturation of North Korea as a malicious actor in cyberspace, Pyongyang has quickly shifted its focus from solely network exploitation and attack for both espionage and disruption, toward the theft of finances as well as the laundering of their proceeds through a web of compromised banks around the world.

Robert Hannigan, former Director of GCHQ

"DPRK cyber activity reflects a rational foreign policy. Pyongyang has the same objectives in cyberspace as in the real world: defending the leader's image, attacking its southern neighbor, building the nuclear program, acquiring foreign currency. They are remarkably consistent. While DPRK is not the most sophisticated cyber actor, it is learning, as it has in the nuclear sphere. Pyongyang clearly saw the value of cyber some years ago and made a strategic choice to invest in cyber skills and capability and to harness wider criminal capacity. It's a low-cost, high-return policy.”

- North Korea deploys its hackers out of its primary covert operations and intelligence agency, the Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB), also known as Unit 586. Their aim is to wage covert operations against the country’s enemies as well as fill the coffers of the North Korean elite and military. Of the seven branches of the RGB, Bureau 121 is the primary cyber operator overseas. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has dubbed hackers working on behalf of Bureau 121 as “Hidden Cobra,” while private cybersecurity firms have labeled them the “Lazarus” group. The group referred to themselves as the “Guardians of Peace” when they conducted the November 2014 attack against Sony Pictures. As of June 2017, North Korea was believed to have 1,700 state-sponsored hackers, with over 5,000 support staff.

- But while the Lazarus group is seemingly responsible for North Korea’s cyber espionage and sabotage, a subgroup dubbed Bluenoroff is responsible for its financially-motivated cyber operations.

- One method Pyongyang has employed to fund its state apparatus is by siphoning foreign currency directly from the backbone of the global financial system. In February 2016, North Korean hackers reportedly obtained legitimate Bangladesh Central Bank credentials for the SWIFT global interbank messaging system, and attempted to transfer $951 million of the bank’s funds to accounts around the world. It managed to make off with $81 million. Similar operations have been waged against banks in developing countries such as Vietnam, Ecuador and the Philippines.

- North Korea also has sought technically savvy ways to launder the proceeds of its cybercrime. In February, cybersecurity firm Symantec reported the discovery that North Korean hackers had laid a trap – known as a “watering hole” attack – by compromising a Polish regulator’s website for a predetermined list of 104 organizations in 31 countries, primarily banks in Poland, the U.S., Mexico, Brazil and China. With access, the hackers could move around their stolen currency until it was not traceable back to the RGB, and ultimately provide hard currency for the Kim regime.

- Beginning in 2017, Pyongyang increasingly set its sights on cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. The Trump administration has officially attributed to the North Korean regime the May WannaCry ransomware campaign that infected more than 300,000 computers across 150 countries, demanding payments in bitcoin. The Lazarus group’s fingerprints also have been found using cryptocurrency miners, or software used to hack a computer to hijack its processing power and mine cryptocurrencies by verifying the transition record, known as the blockchain. The group also has been discovered attempting to breach three cryptocurrency exchanges in South Korea, including Youbit, which lost some $7 million of cryptocurrencies during the heist.

- Targeting exchanges, rather than individual accounts, would allow North Korean hackers to convert bitcoins into more anonymous cryptocurrencies, such as monero, or send them directly to external accounts for withdrawal in fiat currencies such as the U.S. dollar or Chinese renminbi. Given the anonymity that cryptocurrencies can lend and the relatively underdeveloped regulatory environment surrounding them, North Korea’s attraction to cryptocurrencies is likely to continue.

Adam Segal, Director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy Program, Council of Foreign Relations

“We have seen an evolution from attacks designed primarily for political and strategic goals—espionage and disruption of South Korean banks and telecoms as well as coercion of Sony—to financially driven attacks on the SWIFT system, use of ransomware, and theft of bitcoin.”

Robert Hannigan, former Director of GCHQ

“DPRK needs foreign currency and, as sanctions bite deeper, they will try anything that might help create income. Cryptocurrencies are a logical extension of DPRK's interest in cyber attacks against conventional banks, from Bangladesh to Poland. Attacking bitcoin exchanges in South Korea will be doubly attractive.”

Amb. Joseph DeTrani, former Director of East Asia Operations, CIA

“Cryptocurrencies are and will continue to be exploited by North Korea. As sanctions bite and it becomes more difficult for North Korea to move dollars, now they have access to cryptocurrencies that sanctions and its enforcement can't touch. It's perfect for a North Korea that relies on its illicit activities to accrue the revenue needed for its missile and nuclear programs. In short, you have a state actor—North Korea—using its capabilities to function as a criminal organization. As the sanctions continue to bite, we'll see a more active North Korea dealing in cybercrime and exploiting an expanding cryptocurrency market.”

Response: Despite its boisterous rhetoric, North Korea’s conventional capabilities are weak relative to the U.S., requiring it to rely on asymmetric means, such as cyber capabilities, to assert itself. Deterring cyber activity emanating from North Korea will continue to be a major challenge, but there are levers available to counter its growing reliance on cybercrime.

- Tracking Pyongyang’s cybercrime, and the profits incurred, can provide insight into where points of intervention might be, including through traditional means such as sanctions or law enforcement. Even semi-anonymous cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin can be traced through their blockchain ledgers, though identifying the human behind the account remains difficult.

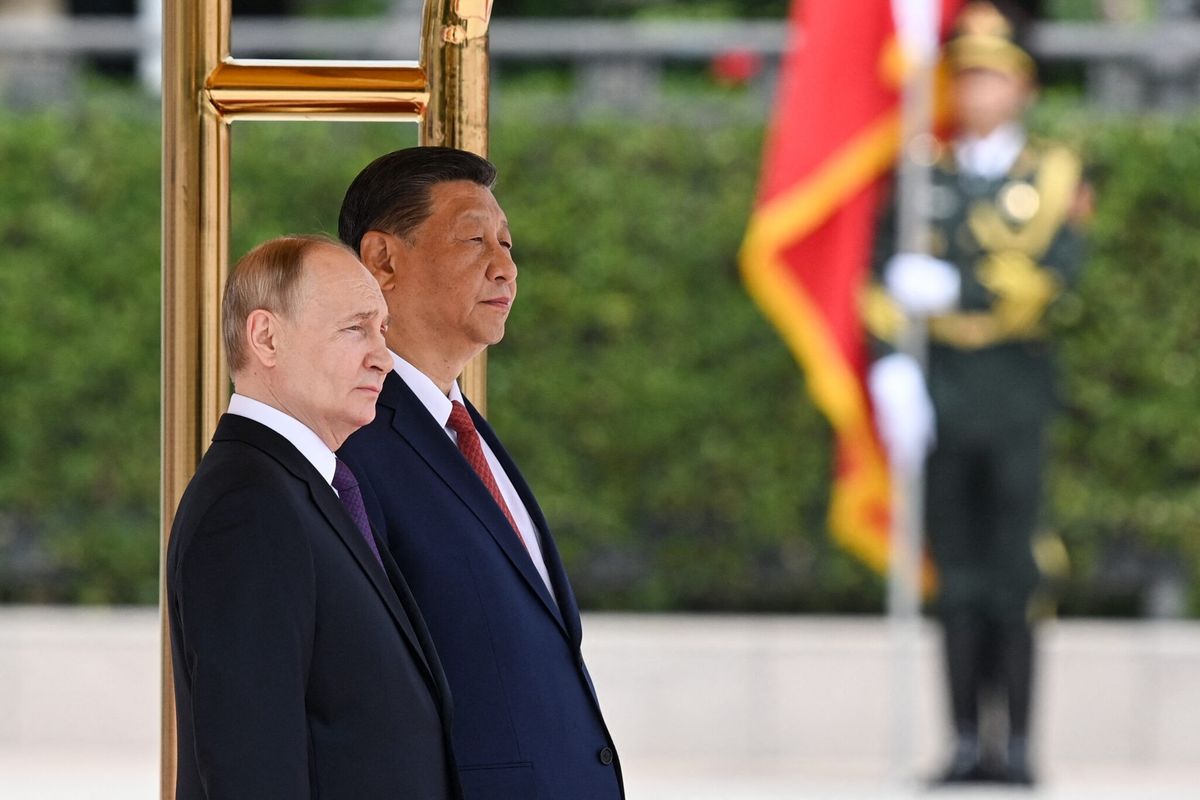

- While Pyongyang’s limited connection to the outside internet – primarily through services provided by Russian and Chinese telecoms – makes it resilient against cyber attacks, it also means that Bureau 121’s cyber operations are largely staged from outside of North Korea’s borders. Pyongyang – likely through fronts established by Office 39 – reportedly co-owns a hotel in Shenyang, China, were North Korean hackers operate. According to research by Recorded Future, a cyber threat intelligence firm, North Korea also has a significant presence in India, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nepal, Kenya, Mozambique and Indonesia.

Anticipation: These incidents might appear to generate only a fraction of the funds needed to finance a mafia state – particularly one developing nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles to hold its neighbors and the U.S. at risk. But compared with a GDP of $16 billion, North Korea’s turn to cybercrime ultimately could add up to a significant impact, and would need to be addressed in any future negotiations, such as the Six-Party Talks. A pivotal 2005 agreement among the negotiating group of North and South Korea, Japan, the U.S., China and Russia called for compliance on a range of activities.

Amb. Joseph DeTrani, former Director of East Asia Operations, CIA

“The Joint Statement of September 2005 dealt not only with the nuclear issue, but other issues, like their illicit activities, as discussions to normalize relations with the U.S. were pursued. Getting them to the table and assuming we can resume negotiations, the aforementioned criminal activities will be addressed. Absent any dialogue, North Korea will expand these illicit activities.”

Levi Maxey is a cyber and technology analyst at The Cipher Brief. Follow him on Twitter @lemax13.