As a landlocked country with three of its immediate neighbors ranked in the top four of the most Fragile States Index, it is in Ethiopia’s interest to be a force for stability in the Horn of Africa. To that end, Ethiopia partners with the United States against terrorist organization al-Shabaab and other mutual foes, and contributes more peacekeeping troops to United Nations missions than any other country in Africa.

Within its own borders, the government of Ethiopia sees equitable economic development as the best way to ensure stability. Its commitment to driving that development has transformed Ethiopia into a global leader in GDP growth, with an average annual increase of more than 10 percent over the past decade. Even so, Ethiopia still ranks in the bottom 15 countries globally on both the UN’s Human Development Index (174 out of 188) and GDP per capita (170 out of 183, according to the World Bank in 2015). Ethiopia has a long way to go to reach its goal of middle-income nation status by 2025.

The Ethiopian government is investing heavily to expand sectors like light manufacturing, renewable power production, and tourism, but Ethiopia’s economy still depends heavily on its agricultural output. Upwards of 80 percent of Ethiopian livelihoods are tied to rain-fed agriculture or pastoralism. Historically, when rains don’t fall, millions face severe food shortages and malnutrition. Ethiopia knows famine.

Public backlash from the 1973 famine contributed to the overthrow of Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie, and in the 1980s, political turmoil and obstruction of aid by the Derg regime exacerbated drought conditions brought on by the 1982-1983 El Niño, increasing food insecurity in the country. Famine followed, resulting in several hundred thousand deaths. That famine further eroded public support in the Derg government, which was eventually ousted by the EPRDF in 1991. Today, the ruling EPRDF coalition is acutely aware of the political risk of a failed drought response, and the government is actively engaged in mitigating the impact of the failed rains.

In 2015 and during the first half of 2016, a severe El Niño climate event resulted in near total failure of seasonal rains in parts of Ethiopia. The drought was worse than in the 1980s. Crops failed. Wells dried up. Livestock died in the hundreds of thousands. Malnutrition rates among women and small children increased, schools closed, and families began selling off assets to survive.

Ethiopia now has more than twice as many mouths to feed as it had in the 1980s. More than ten million people currently require relief food assistance – in addition to the eight million chronically food insecure, who receive support from government programs. Thousands more need specialized nutritional products, and communities need help to fix water systems, dig deeper wells, and improve hygiene to prevent disease outbreaks.

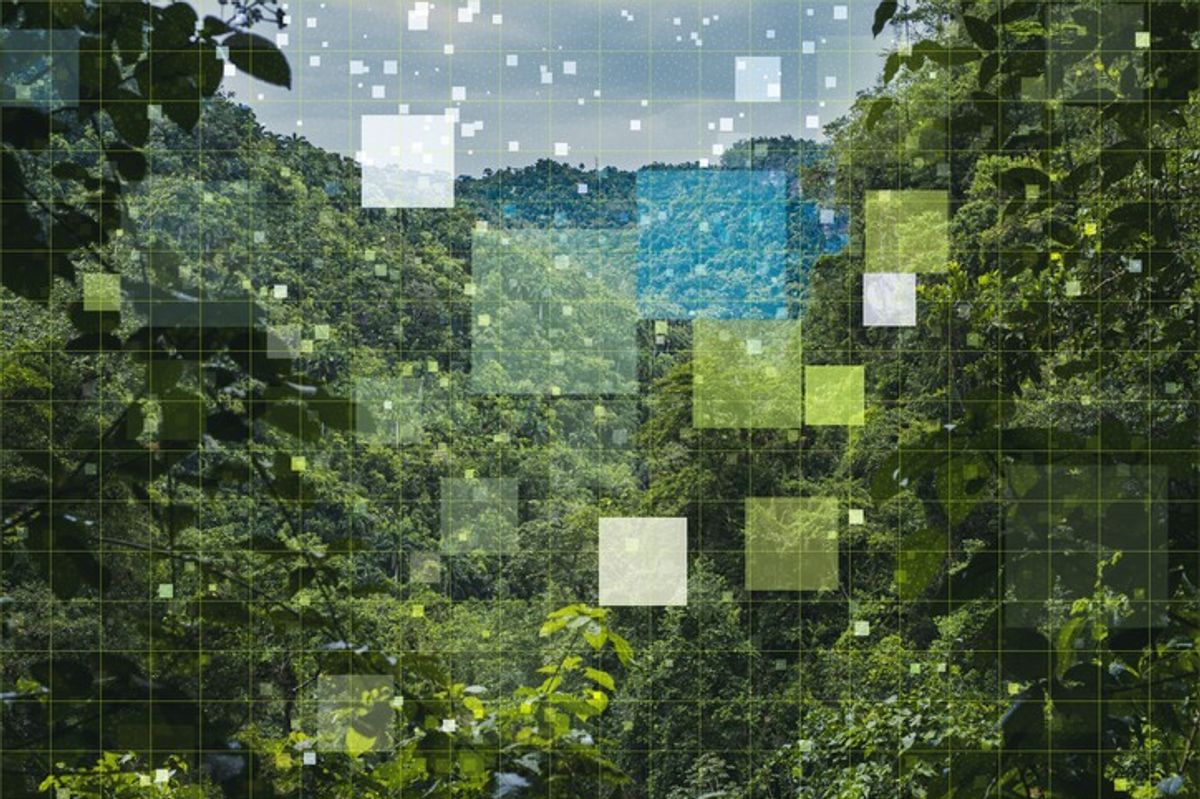

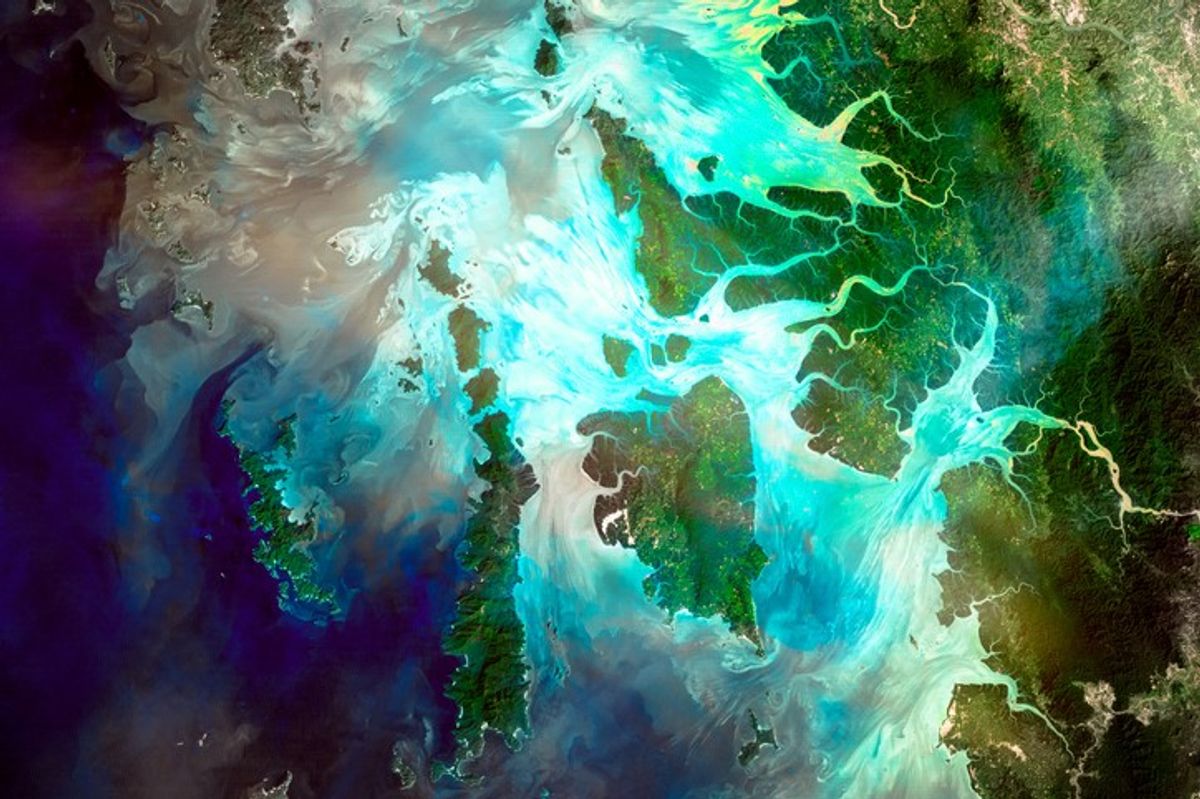

This El Niño’s impact on Ethiopia’s food security was predicted in 2015 and tracked by the U.S. Agency of International Development (USAID) with data from the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Established by USAID in 1985 to provide objective, evidence-based analysis to help government decision makers and relief agencies plan for and respond to humanitarian crises, FEWS NET brings to bear the combined expertise and resources of USAID and other U.S. government agencies – including NASA, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture – together with non-government organizations and affected country stakeholders, such as the National Metrological Agency of Ethiopia.

Based on early warnings and tracking of El Niño, USAID launched an aggressive, multi-faceted response in Ethiopia to help meet the immediate needs of those affected by drought and to accelerate recovery. USAID deployed a Disaster Assistance Response Team in March 2016 to coordinate overall U.S. relief efforts, which include a wide range of life-saving humanitarian programs to provide food assistance, drinking water, malnutrition treatments, seeds, and hygiene and sanitation to people in need.

Since October 2014, the United States has provided more than $706 million in assistance, making it the largest humanitarian donor to Ethiopia. The Ethiopian government also responded to this latest drought with $381 million of its own money, and other donors contributed generously as well.

With U.S. support, the Ethiopia government’s Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) provides food and/or cash to chronically food insecure households in exchange for participation in public works. These works create assets that benefit their communities, while the rations protect existing household assets. In drought affected areas, families are struggling, but many have more coping mechanisms than ever before, lessening the negative impact of the drought.

It is not just humanitarian assistance which has mitigated the impact of the drought. Ethiopia’s investments in development and infrastructure and USAID support have helped increase resilience. Healthcare has improved. Roads better connect communities. More children are in school. Jobs have opened in other sectors.

The international community – including USAID – along with the Ethiopian government is getting seeds to farmers and supporting large-scale seed distributions to help get crops growing again. But it takes time from rain to harvest. July through September are critical months, as farmers wait for their crops to grow and have no reserves at home. All the planning, financing, and efforts to put in systems to prevent wide-scale suffering will be tested, and more resources will be needed to sustain efforts. Moreover, there is a strong chance that a La Niña climatic event will bring severe drought to Ethiopia’s pastoral areas beginning in late 2016; preparations must begin now to mitigate the impact.

The worst possible impact of El Niño has so far been averted thanks to early action by the government of Ethiopia, the United States, and engagement of the international community. The next months will test the strength of the relief operation. Yet, Ethiopia is expected to pull through.

Lessons from this drought will inform development programs that are building the resilience of Ethiopian farmers and guide the government of Ethiopia in preparing for the next drought. There will certainly be a future drought, but thanks to lessons learned, improved coordination, and better preparations, Ethiopia should not need as much help from its international partners when it happens.