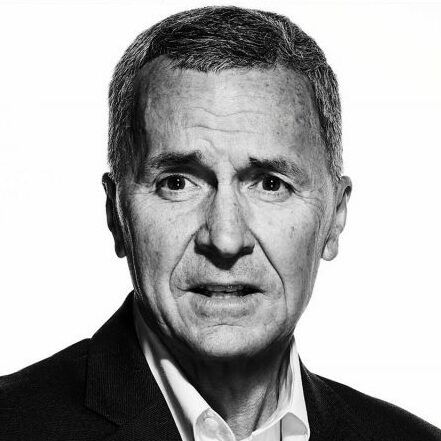

Germany has been hit by four attacks in the past week, three involving refugees. Last Monday, a 17-year-old refugee thought to be from Afghanistan injured a handful of people with an axe and knife on a train near Würzburg. On Friday, 18-year-old Ali Sonboly – born in Germany to Iranian parents – was identified by authorities as the person who shot and killed nine people and injured more than 20 around a shopping mall in Munich. And on Sunday, a 21-year-old Syrian refugee killed a woman and injured two others with a machete in Reutlingen, while hours later another Syrian refugee – a 27-year-old – killed himself and injured a dozen others after setting off an explosive device outside a music festival in Ansbach. The Cipher Brief’s Kaitlin Lavinder spoke with Robert Richer, former CIA Associate Deputy Director for Operations, about these latest attacks, the influx of refugees in Europe, and German immigration policy moving forward.

TCB: Three assailants involved in attacks in Germany over the past week – in Würzburg, Reutlingen, and Ansbach – were refugees. The shooter in the Munich attack on Friday was not a refugee, but was from an Iranian-German family (his parents immigrated to Germany in the 1990s). How much is the recent influx of migration from the Middle East to Germany affecting the security situation in Germany?

Robert Richer: It’s affecting the security situation in Germany in two ways. First of all, the first huge wave of Muslim and Far Eastern immigrants were the Turks. The Turks became established in Germany in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. They practiced the Muslim religion and worshiped at a number of mosques, but they were moderate and became an integral part of society in Germany.

What has happened since then, though, is this second wave of refugees, and now you have groups like the Alternative for Germany party (AfD) pushing against the refugees. Moreover, the first group – the established Turkish group – is pushing against the newest wave of immigrants and with that has come a lot of internal pressures.

The first part of the most recent wave of refugees came in 2012 and 2013. They got into Europe without background checks, because a lot of good-hearted people wanted to take in these people, who were oppressed and were fleeing their home countries, particularly Syria. There was then a subsequent wave of immigrants who came from as far away as India, Afghanistan, and Iran, who latched onto this huge refugee flow because it was an easy way to get into Europe.

So you have a combination of different ethnic and religious groups, opportunists, the economically disenfranchised or criminals, not to mention extremists. You had a year and a half or two years of very little scrutiny of these refugee channels, and now, over the last 15 or 16 months, you’ve had some monitoring of those channels. However, there’s a variety of people who were not scrutinized, who are in Western Europe, and they really don’t have any opportunity. They are living in temporary housing, public housing, or in refugee camps. They have not integrated into society, they’ve got language issues, they’re looking for jobs, and they are ripe for being recruited into extremist groups.

The situation is grave. We’re seeing it not only in ISIS-related attacks, like the ones in Brussels and Paris, but in homegrown immigrants like this guy in Germany who was an Iranian-German citizen, born in Germany, who got trapped into this lifestyle . He took action after seeing some of the successes of these other groups who commit mass murder – not for religious issues or political issues, but for self-satisfaction and mental health issues.

Then you have the Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel situation, where a man who authorities say was involved in petty crime decided to take his truck and kill dozens and dozens of people in Nice, for his own reasons and with kind of a lackluster alignment with ISIS.

So the problem is number one, there are all of these refugees in Western Europe, and we really don’t know who they are. And number two, these people have been sitting now in Europe for two or three years, and they have no job and no future – they feel hopeless and are ripe for recruitment.

The security situation now is as great as it has ever been in Europe. We lived through the 1970s, when we had the Palestinian terrorist groups that were hijacking planes and blowing up airports. But this is the new wave. These are the people who are acting today in the same way as those terrorist groups, whether it’s for religious beliefs, political beliefs, or just a lack of opportunity.

TCB: So you’re saying that these people – like the attacker in Munich, who authorities identified as Ali Sonboly – are learning by example from ISIS-orchestrated or ISIS-inspired attacks but are not necessarily engaged with the ideology, the religion, the politics behind these organizations?

RR: Yes. For example, take this young man who committed this horrible act in Munich. Authorities found his apartment full of articles about mass murders, but they didn’t find a whole lot of extremist political or religious documentation or articles. This is a person who was inclined to this type of activity, who saw the success of crazy people or extremists associated with religious or political acts – like Nice, like Paris, like Brussels – and who wanted to make his own mark in the world. These types of people don’t have political agendas, they have personal agendas, sometimes driven by a mental health issue.

TCB: Do you think the German government is now going to take action on immigration policy? And will there be a political impact, resulting in more support for nationalist parties like AfD and less support for the current government led by Chancellor Angela Merkel?

RR: Anti-refugee sentiment in Germany has been growing measurably since the attacks in Paris and Belgium. Besides the obvious strain on Germany's social services, the growth of refugee "enclaves" within major German cities has alarmed security officials, who are concerned that such enclaves are recruitment grounds for extremist beliefs and groups. German social workers are concerned these refugees are not integrating into German or Western society, and are more dependent on Islamic refugee and religious-related support, which often precludes integration, understanding, and/or acceptance.

Recent German polling indicates that the nationalist AfD party, which is strongly anti-refugee, is growing in popularity. Meanwhile, Merkel's own political party is cautioning her on what many perceive as a too liberal approach to the refugee issue. Finally, some of the strongest anti-refugee sentiment is coming from earlier waves of Muslim refugees, particularly from the East European and Turkish refugee populations in Germany. Both of these established refugee populations see this newest wave of refugees as a threat to jobs and to their own security, both from extremist elements in the newest wave of refugees and from increased German government scrutiny as they are grouped and identified with the new arrivals.

So to your question: Yes, the more these events take place in Europe collectively, countries – even Germany, which has been very liberal in letting immigrants in – are going to push back.

TCB: Is our Western democratic way of living changing, in terms of security versus freedom? Are we going to start seeing more security checks at malls and airports? Are we going to start seeing more states of emergency – like the one in France – in other democratic countries?

RR: You can approach this from a number of ways. Let’s start with the Israeli model, which understands that with more security comes more stability. The Israelis are living in a country which has had serious threats on its border, and they understand that intense security on aircraft, in shopping malls, and everywhere else provides a sense of security, yet they still remain a democracy.

At the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, the Republican presidential nominee painted a picture of an America that is in chaos, where thugs, terrorists, and others are running rampant in the streets, and we have to take a hard line position. That kind of dialogue has gotten pretty wide acceptance.

If you look at Europe, where you have the rise – in France, Germany, Italy, Austria – of stronger right-wing parties, some of which are related to the National Socialist parties of the 1940s and 50s, the answer to your question would be yes: people are willing to give up some of their personal freedoms for better stability.

My question is, how much is what we’re worried about an exaggeration? Yes, Europe has seen more terrorism in the last two years than it has seen in the previous decade, but not more than in the 1970s or 80s, for example. In the United States, all the stats say that crime has actually gone down (even though we’re having these high profile killings either involving the police or against the police). So all that is to say, I think there is unfortunately a perception out there fueling these right-wing nationalist groups on law and order issues, which gets a certain kind of politician elected and helps push their agenda. At the same time in Europe, where they have a very laissez-faire and liberal immigration policy, they understand they have to take more of a middle ground.

There’s a perception that the world has changed – all you have to do is look at some of the commentary coming out of our national convention for the Republican party. There’s a perception in Europe that immigration has upset the balance and is a threat to security on the continent. And there is a growing belief that we can give up some of our personal liberties – empower the police, empower security services – to the better good. I don’t know if, in fact, that is the better good. If you look at what’s going on in Turkey right now, basically the government is using the excuse of a coup to arrest academics and almost anyone who had political views in opposition to the current leader. That’s a dangerous slope.

TCB: Are we going to see an increase in the number of attacks?

RR: There are going to be more copycats, who use everything from guns to axes to knives. Security forces can’t be everywhere all the time. The problem is these people, who are extremists and/or have mental health issues, are going to keep copying attacks until there’s some type of cessation for a long period without such an attack. Unfortunately, we’re going to see more of these attacks, particularly in the disenfranchised communities, which are mostly in Europe right now.