Heads of government from Central America, Mexico, and the United States convened in Miami on June 15 and 16 to discuss security in the Americas, while the Trump Administration plans to cut aid to Central America.

“President Trump has made clear our commitment to this region by requesting an additional $460 million for security and prosperity in Central America,” Vice President Mike Pence said, kicking off the conference June 15. However, that funding request is a 39 percent cut from the current year’s funding.

The Obama Administration – with the help of the current Homeland Security Secretary, John Kelly, then head of the U.S. Southern Command – launched a $750 million initiative to work with the so-called Northern Triangle governments of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to “tackle insecurity as part of a larger matrix of economic, social, and governance issues,” Michael Shifter and Ben Raderstorf of the Inter-American Dialogue told The Cipher Brief.

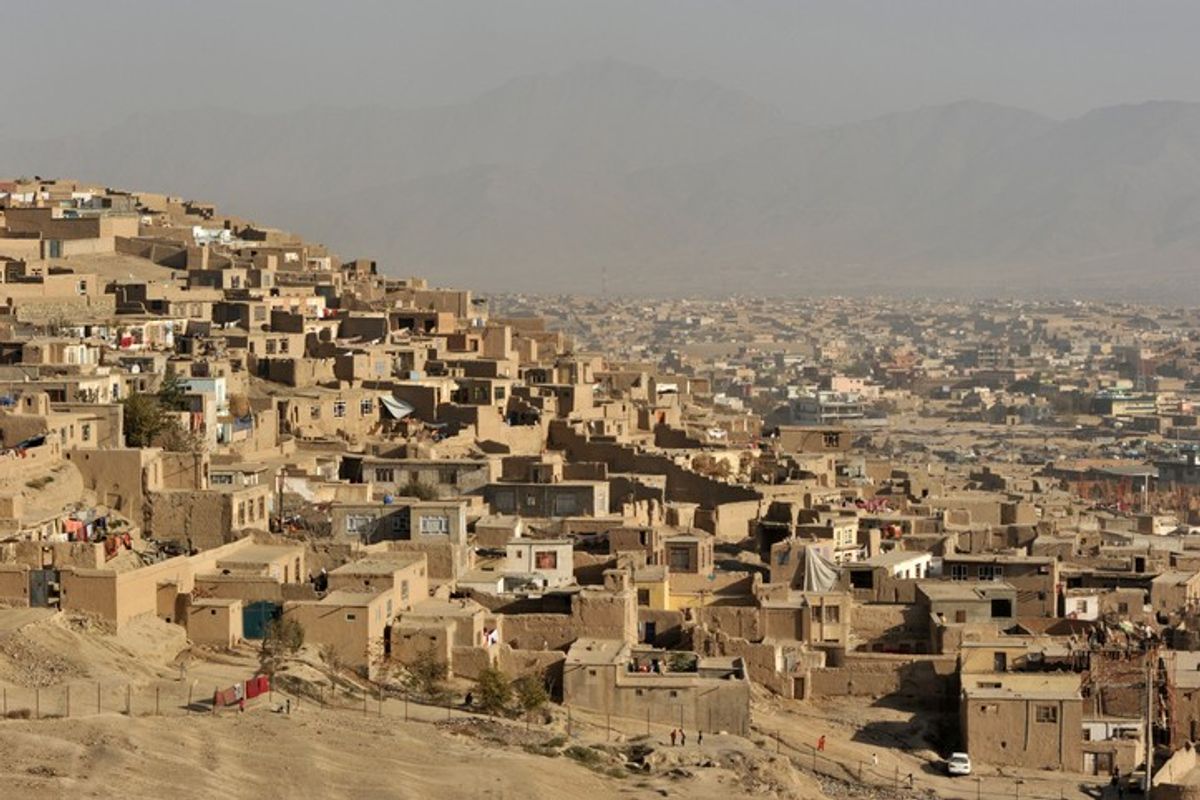

The Northern Triangle is one of the world’s most violent regions because of poverty, poor governance, corruption, and drug gangs.

When the alliance was launched in 2014, the Honduran homicide rate plummeted – a sign the program is working –William Brownfield, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, told Reuters.

The murder rate dropped from 90.4 to 59 killings per 100,000 people from 2012 to 2016, he pointed out.

However, Todd Rosenblum, former Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense and Americas' Security Affairs, told The Cipher Brief, “The percentage of people killed in these countries is incredibly high and horrible … but it also hasn’t really spiked or changed in terms of the amount of violence over the past several years. It’s consistently very bad.”

Rosenblum added that the “surges to our border” from Central American migrants ebb and flow, dependent on “the perception of changes in U.S. law and access to the country.”

“Now we’re in a downward cycle,” noted Rosenblum. That could be partially attributed to President Donald Trump’s rhetoric on making Mexico build a border wall between it and the United States.

It appears the Trump Administration also wants to make Mexico pay for more of Central America’s security – hence, the U.S. cut in aid and the recent Miami conference.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, in his June 15 remarks, said the conference emerged from “our discussions with our counterparts and a recognition of how important Central America was to both of our countries, the United States and Mexico.”

The U.S. is apparently hoping to use that as leverage to rework the Alliance for Prosperity so that Mexico and private investors share more responsibility for improving governance and security in Central America, U.S. and Mexican diplomats told Reuters.

On human trafficking and illegal migration from Central America to the United States, working with Mexico is a necessity, given its geography, but on drug trafficking – the “biggest concern” for the U.S. emanating from Central America, according to Shifter and Raderstorf – the story is a bit more complex.

The drug flow is entirely due to U.S. drug demand for heroin, methamphetamines, and cocaine, Secretary Kelly said in May, adding there is nothing we can do about it here in the United States.

Kelly also noted in May that as head of U.S. Southern Command, he focused on economic development in the Northern Triangle, and that didn’t work.

Former Costa Rican President Laura Chincilla agreed, saying, “Most of the problems we [Central Americans] have today are explained by the amazing amount of illegal drugs [going to] the United States.”

“We have never done well in terms of curbing demand, and the situation, in terms of particularly dangerous narcotics, is getting worse,” said Rosenblum, adding, “Both the use of prescription drugs and the use of opioids is really booming in a very bad way in the United States.”

Unless U.S. demand drops exponentially, drug traffickers will continue to find ways to use Central America as a transit hub to move narcotics from the mass production points in South America – places like Colombia and Venezuela – to the United States, analysts told The Cipher Brief.

In this sense, the Administration’s proposed cut to Central American aid may not be as detrimental to security as it might seem to some outside observers. “If you cut back, it’s not going to be a one-to-one reduction in capability,” said Rosenblum.

Still, “I would argue for giving them more assistance so they could spend more time out on patrol in the air and on their rivers, and control their borders a little bit better,” he said.

The Administration has a different plan, though. Tillerson told a House Appropriations subcommittee hearing June 14, “We have a new initiative underway between the Department of Homeland Security, Secretary Kelly and myself, [and] our Mexican counterparts to take a completely different integrator approach to addressing the supply chain of narcotics to the United States, which deals with where the supply [is] originating from … We are now addressing that through joint efforts to break the supply chain into components which we will address together.”

On the demand side, both Tillerson and Kelly have called for a “comprehensive drug reduction program in the U.S.” Details of how to actually accomplish this have yet to emerge.

“The Northern Triangle countries (like most countries in Latin America) would like to see a solution that addresses demand-side factors – i.e. the voracious appetite in the United States – but the U.S. government is often more focused on halting the supply,” said Shifter and Raderstorf.

—

View our expert commentary on this topic:

Can Central America Break the Cycle of Drugs, Corruption and Gang War? by Michael Shifter and Ben Raderstorf, of the Inter-American Dialogue

Little to Show for Counter-Drug Aid to Central America by Todd Rosenblum, a former senior official at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

Kaitlin Lavinder is a reporter at The Cipher Brief. Follow her on Twitter @KaitLavinder.