OPINION — “The combined impacts of climate insecurities and resource scarcity in fragile states exacerbate poverty and social instability, drive population displacement and unveil governance gaps and grievances that can be exploited by state and non-state actors.”

That’s a quote from the Report on New Security Challenges, released on March 13, by the International Security Advisory Board (ISAB), a Federal Advisory Committee that provides the State Department with independent insight, advice and innovation on national security aspects of emerging technologies, international security and related aspects of public diplomacy.

The 48-page report identified non-traditional security threats currently facing the U.S., listing the first as “climate change and resource scarcity – especially of energy, food, water, and marine life.”

The report also states, “From the tragic floods in Pakistan in 2022 to the prolonged drought across parts of Africa and Latin America, strategic regions are increasingly destabilized by compound climate effects colliding with other factors such as state fragility, weak governance, conflict over identity and inequality, and poor infrastructure and social resilience. These nontraditional security threats are fundamentally reshaping security around the world and have direct implications for foreign policy and diplomacy.” ‘

Today, while most of the U.S. national security focus is on the fighting in Ukraine and Gaza, the ISAB report made me recall past reports and actions that showed that climate change is already affecting national security in this country.

For example, look at the U.S. southern border and recall the words of the October 2021 White House Report on the Impact of Climate Change on Migration. “Surging irregular migration flows to the United States,” the report found, “have increased domestic attention on the politics of immigration, and climate change has the potential to compound related political and social challenges by causing additional displacement.”

The report warned that “the lack of bipartisan agreement on humane border procedures and immigration policies complicates U.S. efforts to mobilize global support for protecting refugees, asylum seekers and other vulnerable migrants.” At the same time, it pointed out that “the current migration situation extending from the U.S.-Mexico border into Central America presents an opportunity for the United States to model good practice and discuss openly managing migration humanely, highlight the role of climate change in migration, and collaborate with other governments to address these challenges.”

That has not yet happened.

It's not just for the President anymore. Cipher BriefSubscriber+Members have access to their own Open Source Daily Brief, keeping you up to date on global events impacting national security. It pays to be a Subscriber+Member.

Meanwhile, in a July 2022 interview, UCLA Anthropology Professor Jason De León, a 2017 MacArthur Fellow, said, “The primary reasons that people attempt undocumented migrations include poverty, political instability, violence of different forms, famine, a devaluation of currency, and, increasingly, climate change.”

De Leon, who directs the Undocumented Migration Project, a long-term study of unauthorized migration crossings between Latin American and the United States, pointed to “people who are fleeing places like western Mexico because of droughts,” and “Honduras because of the intensity and frequency of hurricanes that are just devastating these places.”

De Leon added that “the relationship between climate change and migration is, for me, one of the most understudied and misunderstood parts of our global migration crisis. I think people have tended to want to separate those two things. And if you look at just Central America in the last couple of years, it is very, very clear that as climate change starts to devastate these very poor countries, people are going to start to be leaving in higher and higher numbers. And so we are now living in a moment with climate refugees.”

The more recent U.S. 2024 Annual Threat Assessment, which presents the intelligence community’s baseline assessment of the most pressing threats to U.S. national interests, took a more international view. It stated, “The accelerating effects of climate change are placing more of the world’s population, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, at greater risk from extreme weather, food and water insecurity, and humanitarian disasters, fueling migration flows.”

“Intrastate turmoil,” according to the assessment, “whether grounded in domestic unrest, economic discontent, or governance challenges—can fuel cycles of violence, insurgencies and internal conflict. The challenges often are intertwined with diminished socioeconomic performance, endemic corruption, population dislocations, pressures from climate change, and the spread of extremists’ ideologies from terrorist and insurgent groups.”

The report forecasts that “the risks to U.S. national security interests are increasing as the physical effects of climate and environmental change intersect with geopolitical tension and vulnerabilities of some global systems.”

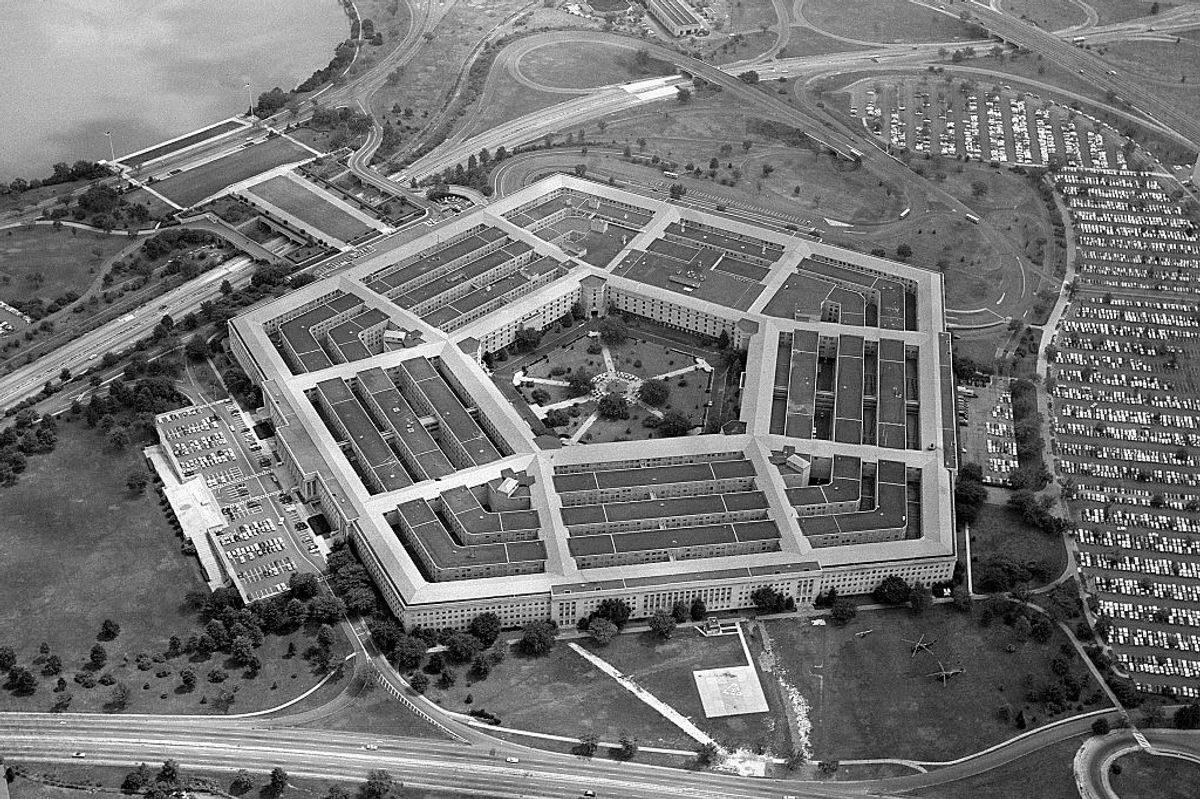

Back in December 2021, President Biden issued Executive Order 14057, “Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability,” which had profound implications for the Department of Defense. The Executive Order’s ambitious goals called for DoD to transition its non-tactical vehicles to a 100% zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) fleet, including 100% of light-duty acquisitions by 2027 and 100% of medium- and heavy-duty acquisitions by 2035.

In 2021, DoD had 181,040 non-tactical vehicles - 71,579 passenger vehicles, 103,694 trucks and 5,767 other vehicles such as ambulances and buses. Of the total, nearly all of them (178,317) had fossil-fuel-burning engines.

When the Biden Administration’s fiscal 2024 Defense Department budget request was sent to Congress in March 2023, it included a 49-page document entitled Enhancing Combat Capability – Mitigating Climate Risk that described how $5.1 billion in defense funds would be used to meet “the effects of climate change across the enterprise and invest accordingly.”

$299.4 million of those funds would go to leasing non-tactical electric vehicles across all the military services to meet the Biden administration goal. The document also referenced a separate $22.0 million in Army funds for construction of ZEV charging infrastructure on Army installations to accelerate progress towards fielding an all-electric non-tactical light-duty vehicle fleet by 2027.

In April 2023, the DoD released its Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions that illustrated the problems in meeting ZEV light-duty vehicle goals. There were neither enough electric passenger vehicles being produced, nor enough installed charging ports on DoD installations.

When it came to ZEV medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, DoD had found in most cases that there were no viable ZEV alternative vehicles available. Pentagon officials began working with industry partners, seeking to test and demonstrate offerings as they developed.

The Biden fiscal 2024 DoD climate change budget drew GOP opposition.

Former President Donald Trump has called climate change a hoax - so needless to say, most House Republicans followed their titular leader and voted to cut $714.8 million from the fiscal 2024 defense budget climate change request. The Republican-controlled House Appropriations Committee’s report called the Biden climate change defense funds “unjustified requests that seek to mitigate climate risk, but do not improve combat capability or capacity.”

The Senate, however, rejected the House cuts in conference and the final measure, which has been signed by President Biden, added $30 million “for additional planning and design and unspecified minor construction for Climate Change and Resilience to mitigate the risks of climate change to military installations and ensure installation readiness.”

The administration’s fiscal 2025 budget request, delivered to Congress last month, calls for investing $23 billion in climate adaptation and resilience across the federal government. And while the budget analysis says that “climate change and extreme weather events are amplifying operational demands on the military, degrading infrastructure and systems, and posing risks to supply chains, especially in austere locations,” the only amount specifically identified for DoD is $3.6 billion “to prevent disruption to operational plans and maintain mission readiness.”

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief