In a recent op-ed published in the Wall Street Journal, titled ‘At the CIA, Immorality Is Part of the Job’, a retired lawyer and former commissioner for Major League Baseball, Mr. Fay Vincent, opined about the CIA’s history and culture, finding it a “farce” to even talk about morality. His position was that CIA officers do not, and should not, consider themselves bound by conventional morals, as their profession is inherently amoral. Mr. Vincent appears to know little about the CIA, has never served there, and is flat wrong.

CIA officers, by virtue of the Agency’s history and culture, rigorous training, continued oversight from both within and outside the Agency, are intensely aware of the criticality of morality. They recognize that intelligence and espionage function at the border of legality, in a secret and compartmented world. They are well aware that a secret intelligence service can be a danger to democracy, and that the skills of the trade; clandestinity and obfuscation, could, if misused, insulate them from consequences. As a result – something I witnessed first-hand — American professional intelligence officers treasure, guard and cherish their morality.

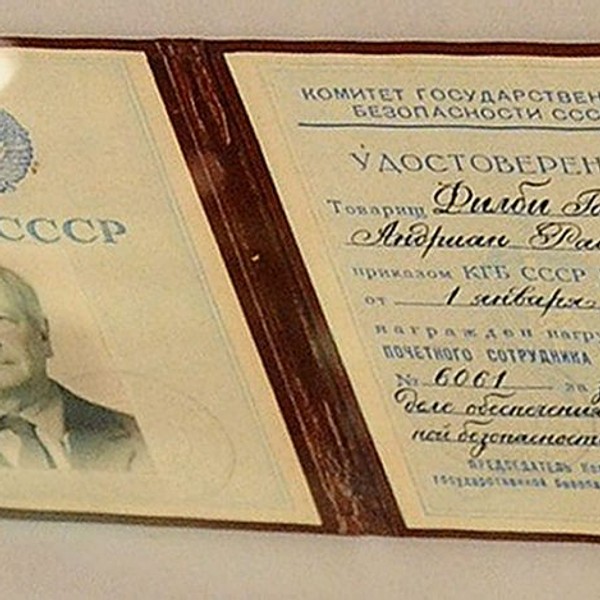

On my very first day at CIA, I participated in the various rituals of “Entry on Duty.” These varied from the mundane (filling out insurance forms) to inspiring (taking an oath to support the Constitution and being sworn in). One of the very first speakers, a veteran agency officer, asked a provocative question of my group of newly-inducted officers: “what is the difference between the job you have taken and a similar job with the KGB?” An impassioned discussion followed. We all realized that it wasn’t how we do the business of espionage (we differ, but the basics of espionage and the concepts of intelligence are the same worldwide); and it wasn’t that American policy, which we would help inform, was “better.” The difference was two-fold. The first has been embodied in our oath – we are a service that obeys the Constitution, and the laws that flow from it. There was no “higher oath” (as Mr. Vincent posits) which trumps the Constitution or law.

The second difference was less rigid, more ambiguous, but equally important. It was the idea that the ship we would be joining would be sailing dark waters, often on the edge of moral maps – and thus we were honor bound to cherish and follow our moral compasses. Morality was central. We would be lying, and concealing, “recruiting spies and stealing secrets.” We would often be in uncharted waters. We would need those compasses.

Mr. Vincent has it completely wrong. CIA officers understand the importance of the Church (and Pike) Committees. They understand why oversight is so important. They understand that violating the law, as former CIA Director Richard Helms did, is not an option to be taken in a special world unbound by law or morality. It is this that makes the CIA different from the KGB, and the STASI, and the Gestapo – not in degree, but in kind.

Mr. Cash served at CIA 1994-2001, first in the Office of General Counsel, and then with the Directorate of Operations. He later served as Staff on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, and Chief Counsel to Senator Dianne Feinstein. Cash currently serves as co-chair of the Bar Association of D.C.’s National Security Law, Policy and Practice Committee, and is Counsel with the law firm Day Pitney in its New York and Washington DC offices.