There is an important emerging gap in thought over whether North Korea is several years away from having the ability to threaten the continental United States with a nuclear-armed missile, which many journalists are reporting, or whether North Korea actually already has that capability now. It’s an important distinction, especially when U.S. thinking, and ultimately, U.S. policy, is based on one of those two assumptions. It’s important to get it right. Cipher Brief CEO Suzanne Kelly sat down with former Acting Director of the CIA Michael Morell to explore whether widespread reporting on this issue, that North Korea is several years away, might be flat out wrong.

Suzanne: An April 24th article in the New York Times suggests that North Korea will not have the ability to strike the U.S. homeland with a nuclear-armed missile until the year 2020. You don’t agree with that, and in fact, you think it is dangerous to assume. Why?

Michael: In the article you reference, the Times reports that the North has not yet developed the capability to target the U.S. with an ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) and that North Korea has not yet made a nuclear weapon small enough to fit on top of an ICBM. At one point, the articles say that those two things won’t happen until 2020, and in another place the article says North Korea is four or five years away – or, by my math, 2021 or 2022.

The Times is not the only media outlet reporting this perspective. In fact, most are. So, it appears to be conventional wisdom that the North cannot yet threaten the homeland with nuclear weapons.

And some policy officials in both the Obama and Trump Administrations, as well as some Congressional officials, have said things publicly that strongly imply that we have time before North Korea reaches the point of being able to threaten the United States with nuclear weapons.

Suzanne: Why then would you say that that's not the case?

Michael: As I have said on CBS and on the Charlie Rose Show, I believe that we have to assume that North Korea today can put a nuclear weapon on the continental U.S., as well as Alaska and Hawaii. Here’s why. First, we know with certainty that North Korea has nuclear devices that work. They have conducted nuclear tests five times, the first over 10 years ago, with varying degrees of success.

Second, North Korea has deployed, but not flight-tested, a road-mobile missile called the KN-08 (an ICBM) that, as advertised, has the range to hit most of the continental U.S., not just the west coast. And, it has successfully put a satellite in orbit with a rocket that, if used as an ICBM, could hit Alaska and Hawaii.

Third, North Korea has long had the technical skills required to learn how to mate a nuclear weapon to a long-range missile, and they have had the time that would be required to do just that.

I think it is important to note that I’m not the only one with this view. Then Director of National Intelligence Jim Clapper told Charlie Rose at an October 2016 Council on Foreign Relations event, “We ascribe to them the capability to launch a missile that has a weapon on it that could reach parts of the United States, certainly including Alaska and Hawaii.” In response to a follow-up question, Clapper added, “We’ve assessed for years that they could do it.”

A year earlier – at an Atlantic Council event in October 2015 – Admiral William Gortney, the then Commander of Northern Command, said, "I agree with the intel community that we assess that they have the ability, they have the weapons, and they have the ability to miniaturize those weapons, and they have the ability to put them on a rocket that can range the homelands.” As Commander of NORTHCOM, Gortney was, among other things, responsible for protecting the homeland from a missile attack.

Suzanne: So, how do we square the two views – one that says that North Korea does not yet have the capability and the other that says that we have to assume that they do?

Michael: The difference is between proven, demonstrated capabilities and unproven, assessed capabilities. The North has not tested a KN-08 (a road-mobile ICBM), nor have they tested a mock-up of nuclear warhead as a re-entry vehicle. So, they have not demonstrated the capability. But, a country can certainly have a military capability without demonstrating it. They are two completely different things.

This is one of the many important lessons from 9/11 – don’t just focus on demonstrated capabilities. Before 9/11, al Qaeda had never demonstrated a capability to use a hijacked commercial airliner as a weapon. But, it turned out that they could do just that. You cannot defend yourself by only focusing on proven capabilities.

Suzanne: Is it possible, with all of North Korea’s grandstanding, that they would have that capability and then choose not to demonstrate it for strategic purposes?

Michael: Hard to say. On the one hand, there is a logical argument for why they may not want to do so. Kim Jong-un may fear that if he tests and the system fails on its own, he would show that he does not have the capability. And, he may also fear that if he tests and we shoot the missile down in flight, he would be embarrassed by the United States, and again demonstrate a lack of capability. On the other hand, all this talk in the United States about him not having the capability yet may lead him to test – to show that he does. We shall see.

Suzanne: I would assume that the U.S. Government is planning, as it usually does, for multiple scenarios when it comes to North Korea. How important is it, then, that the assumption that North Korea has that capability be kept in the public conversation?

Michael: I think it matters a great deal – not only to keep it in the public conversation but also to keep it in the policy discussion. We need to base policy on the assessed capability, not the demonstrated one.

I think the perception that the North does not yet have the capability to attack the United States is extraordinarily dangerous. The perception leads people to think that we can take military action against North Korea without putting the homeland at risk. You can actually see that in some of the recent comments from administration officials about the risks associated with U.S. military action against the North. The focus of their comments is on the North’s conventional retaliatory capabilities, particularly the threat that its artillery poses to Seoul. No one has mentioned the nuclear risk to the United States itself, or even the nuclear risk to South Korea and Japan.

Suzanne: Let’s get technical. If they have the capability, that’s one thing, but how reliable would an untested, nuclear-armed ICBM be?

Michael: Without extensive testing, the probability that a KN-08 and its mated nuclear warhead would operate as designed is low. It would not be reliable. It is also true that the missile would not be particularly accurate. But, even with low reliability and poor accuracy, one has to pay close attention, because we are talking about nuclear weapons.

Suzanne: So, does this mean you are against the idea of the U.S. taking military action against the North?

Michael: No, not at all. I can think of several scenarios where we might take military action, including seeing a KN-08 on a mobile launcher being readied for launch with a trajectory that could take it to the United States – and not knowing for sure whether this was a test or the real deal. That would put the President in a very tough spot, and taking the missile out on its launcher would be a serious option. North Korea would be very wise to never put a U.S. President in this situation.

Suzanne: Here is another variable, if you will. Do you think Kim would ever ‘choose’ to use nuclear weapons against the United States?

Michael: North Korea’s primary purpose for having nuclear weapons and the ability to deliver them is deterrence – deterrence against what Kim Jong-un sees as a desire by the United States to overthrow his regime in P’yongyang. So, logic would tell you, if you don’t threaten the regime, the weapons would never be used.

But never underestimate the chances of a miscalculation. What about a situation where Kim believes we are beginning a military operation to overthrow him, even though we are not doing that? Miscalculations have occurred many times in history. This time it could end with a nuclear detonation over the United States. This is why we have to be extraordinarily careful with what we say and do vis-à-vis the North today.

Suzanne: You and the former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Sandy Winnefeld, recently published in The Cipher Brief a piece on how we should be approaching North Korea. Is there anything you would change in your assessment?

Michael: No. The piece stands, with the basic approach being that our policy focus should be on deterring the North from ever using or proliferating its nuclear weapons. We can achieve this both by denying their objective of putting the homeland at risk via a robust missile defense system and by ensuring that the North knows we can – and we will – impose a steep (proportional but, in fact, existential) cost if they ever use their weapons. Sanctions are useful in signaling other potential proliferators the high economic cost they will pay if they too pursue nuclear weapons; sanctions will not be successful in convincing the North to abandon its weapons program.

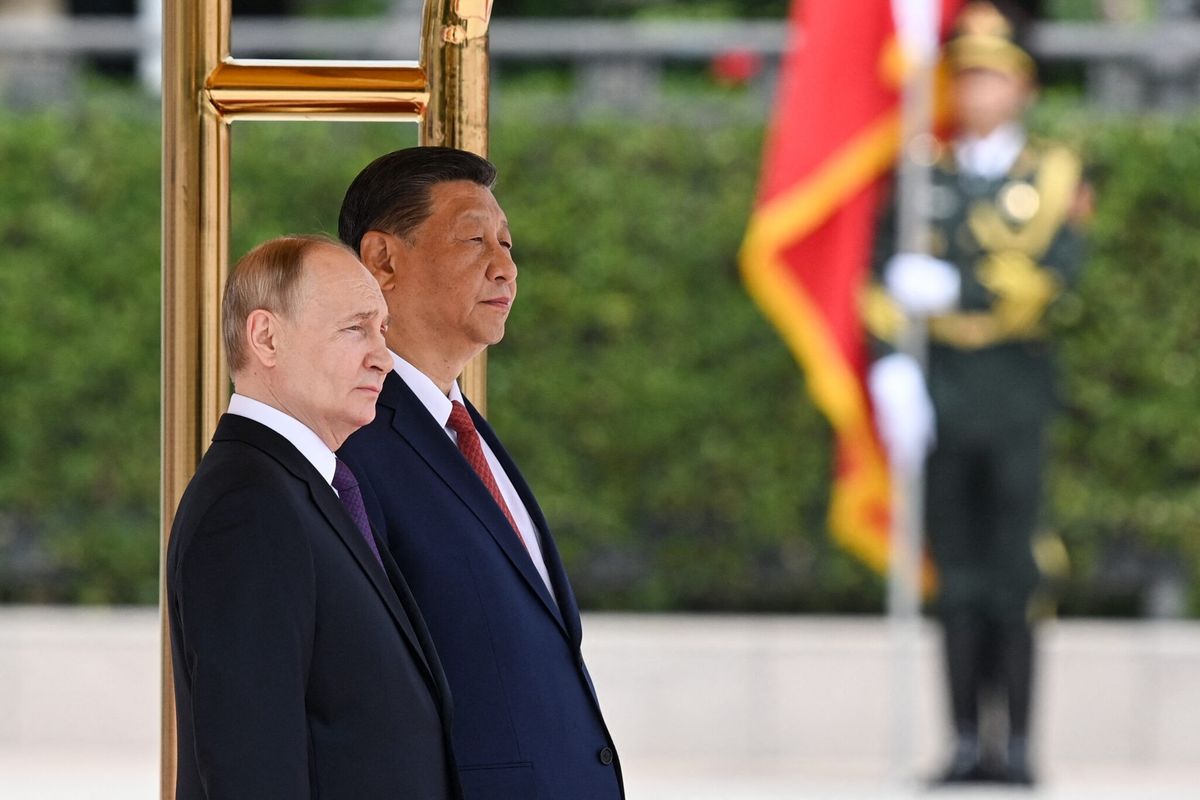

I think the one point I would expand on in the article – which is captured in only one phrase – is China’s ability to change North Korean behavior. I find it interesting that the entire discussion about China’s approach to North Korea is focused on whether China is willing to use it economic relationship with the North to squeeze Kim Jong-un, which they are probably not willing to do for a whole host of reasons. But there is an assumption embedded in the commentary, and quite frankly in the statements of senior policy makers from the last two Administrations, that if only China squeezed the North hard, P’yongyang would change its behavior. I have real doubts about that assumption. The North has shown for a long period of time it is willing to pay a high price for its strategic weapons programs, because they are so important to the survival of the regime.