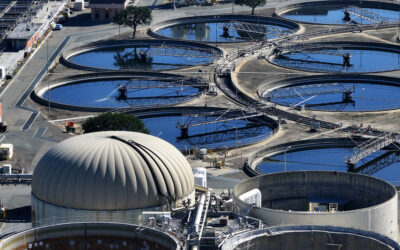

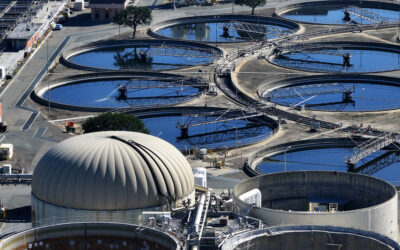

What are Adversaries Doing in the U.S. Water Supply?

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT — It’s a serious threat to the nation’s critical infrastructure that not enough people are talking about. That’s the view of […] More

Most discussions about the North Korea nuclear threat focus on the risk of conflict between the U.S. and North Korea. Serious as that is, an even more important issue is what the crisis will mean for the U.S. and China – the world’s most consequential relationship. Great risk and great opportunity abound.

Will the 21st century be defined by great power war or peace? By prosperity or poverty? The answers depend largely on the course set by Washington and Beijing. But as powerful as both are, each is subject to structural forces not of their own making. Today, as a rising China threatens U.S. predominance in Asia and the international order the U.S. has underwritten for the past seven decades, both sides are locked in the Thucydides Trap. (Thucydides, the ancient Greek historian, was the first to identify the natural tensions between a rising power and the ruling power it seeks to displace – in his case, Athens and Sparta – that can lead to conflict.)

This dynamic leaves the U.S. and China vulnerable to the decisions of third parties: actions that would otherwise be inconsequential or easily managed can trigger reactions by the great powers that lead to disastrous outcomes neither wanted. How else could the assassination of a minor archduke in Sarajevo in 1914 have produced a conflagration so devastating that it required historians to invent an entirely new category – “world war”? In the antics of the erratic (but rational) young leader of North Korea, whom the Chinese security establishment calls “little fatty,” it is not hard to hear echoes of 1914. The challenge for leaders in Washington is to deal with the acute crisis while also developing ways to cope with the underlying challenge in the relationship.

What is the risk? In the next six to 12 months, either Kim Jong-un is going to demonstrate that he can reliably put a U.S. city at risk of nuclear attack and we are going to (reluctantly) accept that, or President Trump is going to try to prevent that from happening by ordering U.S. airstrikes on North Korea. Remember: upon becoming president-elect, Trump vowed that he would not allow North Korea to develop the capability to hit the U.S. with a nuclear weapon. A cruise missile attack like the one Trump ordered on Syria after the opening dinner for Chinese President Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago is not difficult to execute. The question is what would come next.

No one knows for sure. But the best judgment of North Korea experts is that the North will respond by raining artillery shells down on Seoul – the center of which is just 35 miles from the border between South and North Korea – killing tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of its more than 25 million citizens in just the first 24 hours of fighting. It is simply not possible for a U.S. preemptive strike to remove all the North Korean artillery along the border before it can fire on Seoul.

As that is occurring, what will South Korea and the U.S. do? Again, while nothing is automatic, plans call for the obvious: attacks on the weapons that are firing against Seoul. In addition to the artillery on the border, the U.S. and South Korean counterattack would almost certainly target the several thousand other North Korean rockets and missiles that could attack South Korea (including missiles that could carry nuclear warheads). Whether that attack would also attempt to kill Kim Jong-un and the leadership in Pyongyang involves another decision by the President. But the critical point is that after a U.S.-South Korean response against several thousand targets in the North, the second Korean War would have begun.

Secretary of Defense Mattis has offered his considered assessment of such a war in recent testimony before Congress. He has warned candidly that a second Korean conflict would be catastrophic, causing loss of life, including both U.S. combatants and U.S. civilians living in South Korea, unlike any we have seen since the first Korean War. But he has also assured members of Congress that at the end of that war the U.S. would “win,” Korea would be unified, and the Kim regime would be gone.

The question he has not addressed, and which no member of the committees before which he has testified has asked him, is: “what about China?” That was the question General Douglas MacArthur infamously failed to consider in October 1950, when U.S. troops who had come to the rescue of South Korea pushed the North Korean aggressors back up the peninsula. MacArthur imagined that he would unify the country and start bringing American troops home before Christmas. Since this was just five years after the U.S. had ended World War II by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and less than a year after Mao had won a long, bloody civil war, the thought that a nation with a GDP one fiftieth the size of America’s would attack the world’s uncontested superpower was inconceivable. But Mao did. And his force of 300,000 fighters, followed by a second wave of half a million, beat American forces back down the peninsula to the 38th parallel where the U.S. had to settle for an armistice.

As a member of the Chinese security establishment explained to one of us in a recent conversation, Beijing will not permit a united Korea allied with the U.S. on its border. From a Chinese perspective, that point was written in blood when Mao’s China entered the first Korean War. And they will do so again if Beijing believes that is the U.S. intention or the likely result of a U.S. and North Korean conflict. Indeed, just last month, the Chinese warned publicly that if the U.S. preemptively attacked North Korea, China would fight on behalf of Kim Jong-un.

This is a not a war we would want the U.S. to fight. No one should forget that the first Korean War claimed the lives of tens of thousands of Americans, hundreds of thousands of Chinese, and millions of Koreans. With China’s extensive military modernization over the last two decades, particularly the deployment of weapon systems designed to deny U.S. access to the battlefield, the Chinese might even win the war — or force the U.S. to settle again for an equivalent of the armistice accepted in 1953. Such outcomes would mark a turning point in the balance of power in East Asia, if not the world. After World War II, the U.S. emerged as the leading global power. After a second Korean War, China might wear that mantle.

A similar risk of conflict between the U.S. and China exists in the other, and perhaps more likely, path that the U.S. could take in the near-term regarding the North Korean nuclear crisis – acceptance of the North’s nuclear weapons capability along with containment and deterrence to deal with the threat. The problem with this option is not only that it leaves Kim with an ability to strike the U.S. homeland with nuclear weapons but also that Kim could see that capability as a tool to coerce the U.S. and South Korea to get what he wants – first, the withdrawal of U.S. forces from the Peninsula and second, reunification on his terms. Kim could calculate that since the U.S. was not prepared to risk war to prevent it acquiring the capability to attack American cities, the U.S. would not be willing to trade Chicago for Seoul. And, in taking provocative actions based on this assumption, Kim could bring the U.S. and North Korea to war – again with the risk of China joining the fight.

What then is the opportunity? Our vital national interest in North Korea is to ensure that Kim Jong-un cannot threaten the U.S. and our allies and partners with nuclear weapons. China shares this interest because Beijing understands that as the North Korean threat grows, the U.S. and its allies will move to protect themselves with missile defense, a development that would also put Chinese missiles and therefore China’s deterrence at risk. Beijing also knows that South Korea and Japan may well respond to a North Korea armed with nuclear-tipped missiles by developing their own nuclear weapons, a serious and threatening development from China’s perspective.

Given these converging interests, can we imagine American and Chinese diplomats finding common ground on a vision for the future of the Korean Peninsula — one without nuclear weapons — and developing a cooperative approach to achieve it that might start with significant limits on what North Korea has at present? If such cooperation were to result in eventual denuclearization of the North and enhanced stability in Northeast Asia, it would act as a bright shining beacon of what the U.S. and China could achieve working together. It would build trust in both capitals. It would be a major step forward in managing the Thucydidean tension in the relationship and pushing the two countries away from conflict and toward cooperation.

How do we get to a place with the Chinese where we can have such a conversation about North Korea? It cannot be through threats. We cannot achieve this by publicly scolding China over not doing more to pressure Kim Jong-un, by publicly raising the prospect of war between the U.S. and North Korea in an effort to frighten Beijing into action, or by publicly offering China a deal whereby they pressure North Korea in exchange for the U.S. backing away from action on Chinese trading practices. None of these will move China to act. They are too proud a nation and a culture to be bullied, bribed, or threatened into action.

Rather, the potentially productive path forward is to sit and talk turkey with the Chinese – in private, even secretly – about their real national interests and ours. President Trump and President Xi should ask one or more of their most trusted senior officials to sit down for several days of hard conversation and come back with feasible, if ugly, options for a joint way forward.

For inspiration, they could read the transcripts—now declassified—of the initial conversations between Henry Kissinger (as Nixon’s national security adviser) and Zhou Enlai (Mao’s most trusted lieutenant). They could reexamine what John F. Kennedy did when he came to the final fork in the road confronting the Soviet Union over its attempt to place nuclear-tipped missiles in Cuba. They could consider what Obama did in sending Bill Burns and Jake Sullivan to secret talks that developed a path to prevent (or at least postpone for a decade) Iran’s quest for nuclear weapons.

Critics will shout: “but in every one of these cases the U.S. compromised!” Yes, to achieve what these presidents judged vital for our country, they sacrificed other interests. To open relations with China in order to encourage its split from the Soviet Union, Nixon and Kissinger agreed to de-recognize Taiwan as the government of China and recognize Beijing (a decision that was officially implemented under President Carter). To escape the choice between accepting an operational Soviet nuclear base in Cuba and an attack on the missiles, Kennedy promised—secretly—that if the Soviet missiles were withdrawn, six months later, equivalent U.S. missiles in Turkey would be removed. And as Iran’s nuclear program had advanced to a point that it stood just 2 months away from its first nuclear bomb, Obama signed an agreement that allowed Iran to keep a limited uranium enrichment program in exchange for pushing its nuclear program back to at least a year away from a bomb.

Ronald Reagan was determined to bury Communism. But to advance that cause, he repeatedly engaged in negotiations with the Soviet Union and reached arms control agreements that constrained or even eliminated American nuclear and missile programs as the price of stopping Soviet advances that threatened us. For this, many conservative supporters attacked Reagan. For example, George Will accused Reagan of “accelerating moral disarmament” and predicted that “actual disarmament will follow.” But as Reagan’s Secretary of State George Shultz noted: “Reagan believed in being strong enough to defend one’s interests, but he viewed that strength as a means, not an end in itself. He was ready to negotiate with adversaries and use that strength as a basis of the inevitable give-and-take of the negotiating process.”

To persuade China to join us in taking responsibility for North Korea, and use its leverage to stop Kim’s nuclear advance and begin rolling back his program, what incentives could Trump’s secret negotiators offer as a reward for success? The Trump Administration and its predecessors have insisted that we will not make changes in our own military forces to reward North Korea or China for stopping bad behavior. But there is nothing sacrosanct about the number of U.S. troops who participate in the regular fall and spring joint military exercises with South Korea. In fact, the recent exercise included only 17,500 American soldiers, a 30 percent reduction from the 25,000 who participated in the 2016 equivalent. Though Trump has steadfastly resisted Xi’s call for a “freeze for freeze”—a freeze in North Korean nuclear and missile tests in exchange for a freeze in U.S./South Korean military exercises—some variant of that should be considered as part of the solution, given the alternatives. Even more enticing to China, the U.S. could offer to delay or even cancel and roll back deployment of missile defenses, including the THAAD batteries in South Korea, if China took actions that mitigated or eliminated the threat.

We recognize serious objections to each of these possible concessions and others. Indeed, we have often voiced them. But the brute fact is that, at this point, U.S. choices have shrunk to the zone between the horrific and the catastrophic. Accepting a nuclear-armed North Korea that can hold American cities hostage to a nuclear attack and attempting to live with that threat by a combination of deterrence and defenses would constitute one of the highest risks that the U.S. has faced in the seven decades of the nuclear age. Attacking North Korea to prevent that outcome will likely lead to a catastrophic second Korean War that could find thousands of Americans and Chinese killing each other.

Before choosing between these terrible options, we urge President Trump to explore a third way through candid discussions with the Chinese of options that heretofore have been “unacceptable” but that are in fact preferable to the alternatives. Kennedy and Khrushchev did. So, too, did Reagan and Gorbachev. There is no guarantee that such talks with China or the subsequent joint approach to North Korea would work – Chinese influence with North Korea may be more limited than most think – but we owe it to our security and to history to try.

If there is a better way out of the North Korea crisis, it will be through Washington and Beijing working together. For leaders determined to construct a productive U.S.-China relationship, North Korea offers a great opportunity. It also offers perhaps the greatest challenge and risk to that relationship, and therefore to U.S. leadership in the world, since the end of the Cold War.

Michael Morell is host of the new weekly national security podcast, Intelligence Matters.

Related Articles

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT — It’s a serious threat to the nation’s critical infrastructure that not enough people are talking about. That’s the view of […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — Russia’s reaction to the new infusion of U.S. aid for Ukraine has ranged from shrugs to fury, from warnings of nuclear […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — When Chinese President Xi Jinping came to San Francisco last November to meet with President Joe Biden, Chinese pro-democracy activists in […] More

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE EXPERT PERSPECTIVE — More than two years after its withdrawal from Afghanistan, the U.S. still does not have a clear way forward in the […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — Ukrainians greeted Saturday’s long-awaited House passage of $60.8 billion in aid with justifiable jubilation. For months, their soldiers, civilians, and political […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — A race for control of space is underway, and just as on earth, the U.S. and China are the top competitors. […] More

Search