Bottom Line: A 2015 peace accord between the Mali government and ethnic Tuaregs in the north of the country has failed to produce economic or security benefits for the northern tribe, with each side blaming the other for the failure of the deal. The dispute could devolve once again into civil war, and create an opening for al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and other terrorist groups to further fortify their continuing operations in the northern part of the country.

Background: Mali achieved independence from France in 1960, but has since been plagued by civil wars fought between the central government and the Tuareg ethnic group based in the northern part of the country.

- Northern Mali, also known as the region of Azawad, is comprised of three provinces – Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal.

- Mali has suffered through four brutal civil wars fought between Tuareg rebels from the north and the central government in the south, which occurred in 1963-1964, 1990-1996, 2006-2009, and 2012-2015.

- The most recent conflict was initiated in March 2012 when a group of military officers overthrew the elected civilian government of President Amadou Toumani Touré one month before scheduled presidential elections. In April 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), which was headed by Taureg rebels, teamed with jihadist groups including AQIM, Ansar al-Dine and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) to expel Malian forces from Azawad and declare independence.

- However, during the ensuing months, the jihadists turned on the MNLA, forced Tuareg fighters out of Gao, Kidal, and Timbuktu, and began imposing harsh forms of sharia law in newly conquered northern territories. The terrorist groups managed to capture previously Tuareg-held territory larger than the size of France.

- In January 2013, French forces intervened in Mali, launching Operation Serval, and successfully repelled a southward jihadist advance aimed at seizing the Malian capital of Bamako. The French subsequently initiated Operation Barkhane in August 2014, which led to the deployment of 4,000 French troops into Mali to combat the insurgents. The operation also facilitated a longer-term French security presence in northern Mali, as approximately 1,600 French troops remain in northern Mali.

- In April 2013, the United Nations also established a peacekeeping mission in Mali, known as the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission (MINUSMA) to help bring stability to the country. As of December 2017, MINUSMA was comprised of more than 13,000 security personnel.

- In 2014, representatives from several factions in the north, including the MNLA joined together to form a coalition known as the Coordination of Movements of Azawad (CMA). The CMA signed a peace agreement with the Malian government in June 2015 after months of Algerian-mediated talks, which mandated: increased northern representation in government institutions; the inclusion of rebel fighters in a newly-formed security force to be deployed to the country’s north; and the creation of local police forces that will provide security for cities in the north.

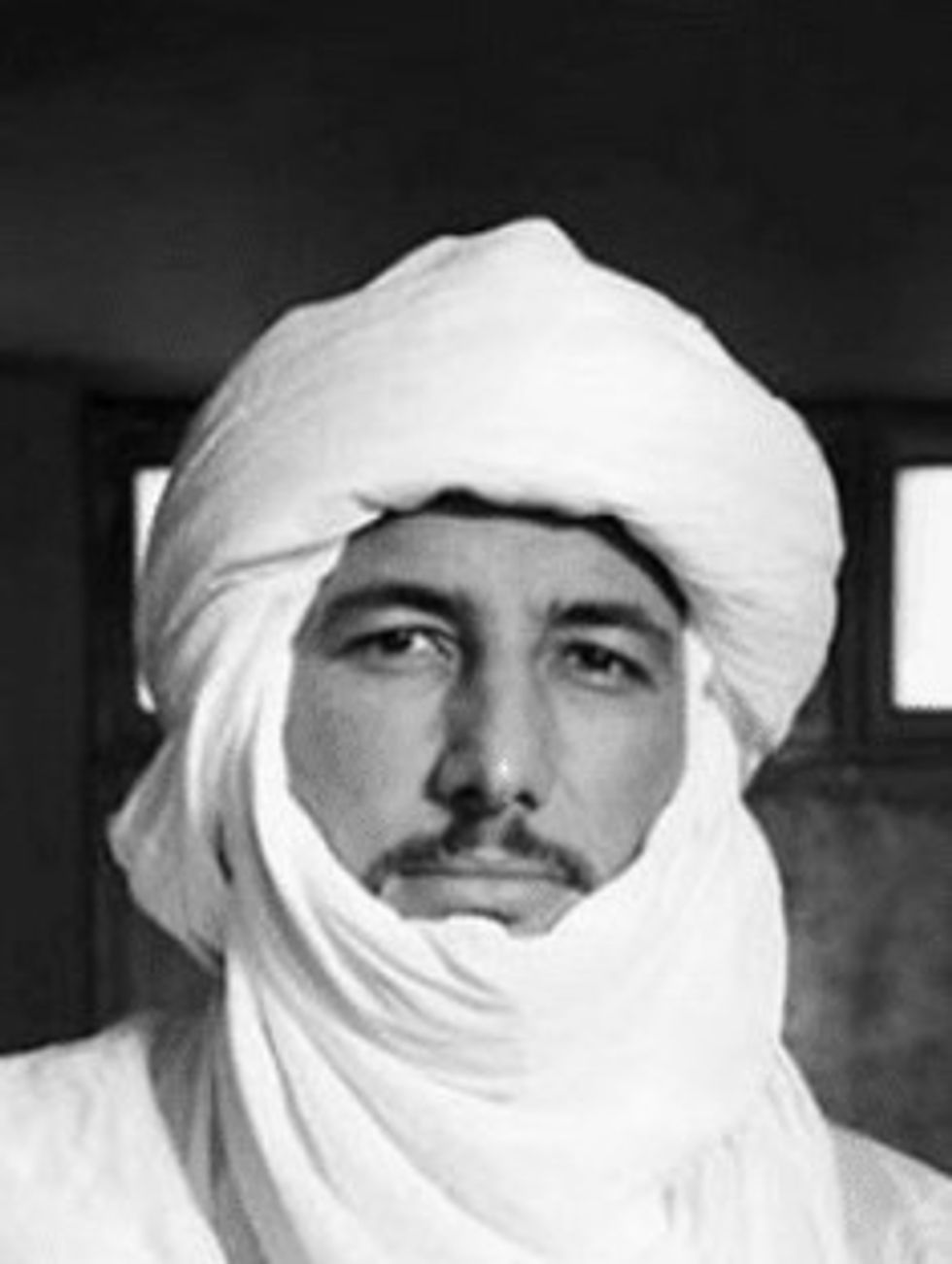

John Bennett, former Director of the CIA's National Clandestine Service

“The underlying issues between the central government in Bamako and the nomadic population of Northern Mali pre-date the emergence of al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), but AQIM has certainly taken advantage of those tensions. An indigenous force, properly trained, equipped and supported would certainly have a better chance of defeating the terrorists than foreign troops or government forces from outside the region.”

Issue: The persistent terrorist threat emanating from northern Mali directly intersects with the ability and willingness of both the central government and separatist groups in the north to implement the peace agreement. Terrorist groups, such as AQIM, prey on local grievances and win over the support of the local population by providing key economic, social and security services that the state fails to deliver.

- The June 2015 peace agreement currently risks failing as both sides accuse the other of failing to fully implement their responsibilities. Representatives from the north, including Bilal Ag Cherif, the Secretary General of the MNLA and former executive president of the CMA, and Alghabass ag Intalla, former executive president of the CMA, told The Cipher Brief that the government has failed to adhere to the agreement as it has not created agreed-upon local police forces, integrated fighters from the north into the national army, or implemented critical economic development programs in the north.

- However, the central government asserts that it has implemented parts of the agreement but has been hampered by the CMA’s failure to: abide the schedule outlined in the agreement; provide key lists of figures who will be incorporated into the government; and agree to hold elections that will move the process forward. Furthermore, many in Bamako have questioned linkages between the CMA and terrorist groups in the north, while the CMA has claimed that opposite – namely that elites in Bamako are the ones who have ties to terrorist networks.

- The failure to implement the accord has benefitted AQIM, which has used northern Mali as a safe haven from which to orchestrate attacks across the Sahel including several western hotels in Mali and in neighboring Burkina Faso. A unified front comprised of forces from the Malian government and the CMA offers the most effective way for combatting terrorist groups in the county.

- Of all the al-Qaida affiliates, AQIM is most notorious for snatching foreigners and turning hostages into profit. Between 2008 and 2014, AQIM received approximately $91.5 million dollars in ransom payments, nearly three times the amount of the second largest total generated by al Qaeda’s Yemeni offshoot during that same time span. AQIM’s aptitude for hostage taking was enhanced after it relocated in northern Mali, a popular destination for western tourists and aid workers.

- AQIM is not the only terrorist organization that has carved out a stronghold in northern Mali in recent years. Other jihadist groups such as Ansar Dine, led by Iyad Ag Ghaly, and al Mourabitoun, led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, have also taken advantage of Mali’s political volatility to establish sanctuaries where they can organize, plan and coordinate attacks. Last March, the two groups, as well as the smaller Macina Liberation Front, merged into one entity called “Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen,” or the Group to Support Islam and Muslims, under the leadership of Ansar Dine’s Ghaly, and pledged allegiance to Taliban leader Mullah Haibatullah, al-Qaida emir Ayman al-Zawahiri, and the head of AQIM Abu Musab Abdul Wadud.

Rida Lyammouri, independent security and development consultant focusing on the North Africa and Sahel regions

“When you look at how AQIM and its local brigades, and later on Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS), integrated themselves in the northern Mali and in the Sahel more generally, it is by building trust with local communities, exploiting grievances toward central government and playing differences between communities in their favor, and providing some of them some basic services like health, security, justice to fill the void left by the state. Now it is very challenging for the Malians and also for foreign interventions, such as the French or MINUSMA, to help gain that trust back.”

Rudy Atallah, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Africa Center, Atlantic Council

“Every time they come up with a peace process, the north agrees and the south drags their feet and drags their feet and in the end, nothing happens. Today in the north, they have to deal with an angry population, a stalled peace process and an exclusion in a lot of the goods and other important items that are important for life. They don’t have proper medical care or proper school for their kids. Everyone calls them terrorists when the opposite is true.”

Bilal Ag Acherif, Secretary General of the MNLA and former Executive President of the CMA

“On the ground, the northern part of Mali has difficult areas and is controlled by people who know the area well. These people have the capacity and skills to deal with the terrorist threats if they received official training from the government, but both local forces and the Malian government are acting alone – there is no official connection.”

Colonel Major Sory Ibrahim Kone, Defense Attache of Mali to the U.S.

“Right now you see the CMA has its troops stationed somewhere else, and it’s only the Malian armed forces fighting against the terrorists. People from the CMA know the region better so if they join the Malian army, we can defeat the terrorist group. But they cannot just stand there and say that it is not their problem. And the agreement says that we must come together. That is why people want them to clarify their position because, for example, if you take one of the components of the CMA, they are a group that comes from Ansar al-Dine and are led by Alghabass ag Intalla who himself comes Ansar al-Dine. We need to know if they are still part of Ansar al-Dine or only part of CMA. If they can come to fight the terrorists, we will know that they are not part of Ansar al-Dine.”

Response: The U.S. has kept a watchful eye on developments in Mali, particularly as the situation on the ground has paved the way for terrorist groups to accumulate strength. Washington has supported several counterterrorism initiatives undertaken by the Malian government and has actively trained Malian troops to combat terrorist organizations in the northern part of the country.

- The U.S. State Department in January reaffirmed its commitment “to international efforts to help Mali restore peace and stability throughout its territory following the 2012 rebellion in the north, a coup d’etat, and the loss of the northern two-thirds of the country to violent extremist groups.”

- The U.S has provided critical aid to Mali totaling more than $125.1 million in FY 2016 and an additional $117 million being requested for FY 2017.

- In February 2014, five countries – Mali, Mauritania, Chad Niger, and Burkina Faso – formed a unified front, known as the G5 Sahel the terrorist threat in the region. Through this initiative, G5 member states have deployed roughly 5,000 troops that have started joint patrols aimed at stemming the flow of terror groups and traffickers across the porous borders in the Sahel. In October 2017, the U.S. pledged $60 million is support of this new counterterrorism effort.

John Bennett, former Director of the CIA's National Clandestine Service

“While the U.S is very focused on Mali as a counterterrorism issue providing various forms of security assistance, it strikes me that we are less comfortable tackling the ethnic and cultural issues that have fueled the insurgency and played into the hands of AQIM. Of course without basic security on the ground it is difficult to do much outside the security assistance domain.”

Barbara Worley, Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Boston

“The U.S. needs better information about the local people, and more direct, positive, interactions with the Tuaregs, in particular, to gain their trust and cooperation. The U.S. wants to maintain influence and economic power in the region, but U.S. policy is not working in Mali - particularly in northern Mali. Too often, the U.S. is willing to listen to elites in Bamako, who want to frame Tuaregs as bad guys, for their own economic benefit and racist prejudices. The U.S. needs the support of the local people, by talking with them, through person-to-person relationships, and by providing much-needed development with oversight of funds so they don't get pocketed by elites in Bamako.”

Colonel Major Sory Ibrahim Kone, Defense Attache of Mali to the U.S.

“The U.S. and Mali have a good relationship. Right now, there is an important partnership centered around anti-terrorism assistance and special operations training. The U.S. has engaged in several initiatives to help Mali build a better military component. That is very important for us. Overall, the U.S. is one of Mali’s best partners. Some countries fighting in Mali are just looking for natural resources, but we realize that the U.S. wants to help us for better living, democracy and to fight terrorism because they don’t want it to spread in the world.”

Looking Ahead: With an unstable peace agreement looking more fragile by the day, it is likely that Mali will face another insurgency in the coming years and terrorist organizations will continue to operate unperturbed in a vacuum spurred by the ongoing inability to bridge the gaps between north and south Mali. In light of this situation, the U.S. may also aim to bolster its special operations forces in the region, particularly in the frontier area between Mali and Niger where the U.S. already maintains a key drone base.

Barbara Worley, Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Boston

“The rebellions have become cyclical. When people live in constant fear for their well-being and have no democratic process or political solution available, it's possible that anything could happen. The Malian government seems to be pushing the Tuaregs into a corner. The human rights abuses and attacks are non-stop. There is no let up. The international community needs to see the big picture, and understand that Mali is a mess. No amount of military assistance, "capacity" training, or weapons will ever bring peace in Mali. Elites in Mali want the conflict. They pocket the foreign aid from the U.S., as well as the payoffs from the terrorists who are securitizing the South American drug traffic. Nothing is going into local development. The country is wasting away, and chaos is increasing. Mali is on track for more conflict, because elites are getting rich off of it.”

Bennett Seftel is director of analysis at The Cipher Brief. Fred Ludtke contributed to this report.