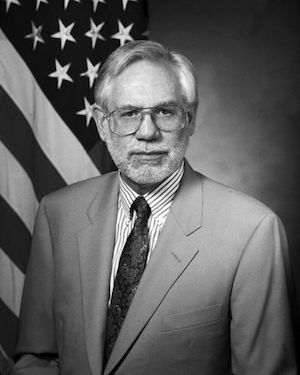

The United States relies on missile defense systems to protect its allies and its troops stationed all around the world. Yet in some instances, the deployment of such systems is a strain on regional stability. The Cipher Brief spoke to Philip Coyle, a senior science fellow at the Center for Arms Control and a former assistant secretary of defense, to learn more about the conditions that turn missile defense into a diplomatic issue and how these tensions can be alleviated.

The Cipher Brief: What diplomatic strategies do countries use when deploying missile defense systems or when responding to another country’s deployment of a system?

Philip Coyle: Countries deploying missile defenses are surprisingly tone deaf when it comes to their diplomatic strategies. For example, with respect to U.S. missile defenses in Europe, basically the U.S. has been saying to Russia, “Trust us. This isn’t about you,” even as the U.S. advertises that it intends to expand the system to have capabilities that could be a threat to Russia’s strategic deterrence forces.

When responding to another county’s deployment, countries typically either threaten consequences, build and deploy their own missile defenses, and/or actually build and deploy more offensive forces so as to be able to overwhelm or bypass those missile defenses. For example, Russia has deployed offensive Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad in response to U.S. deployments of missile defenses in Europe.

TCB: Countries often object when a neighboring state wishes to deploy a missile defense system. What strategic considerations make missile defense systems a contentious diplomatic issue?

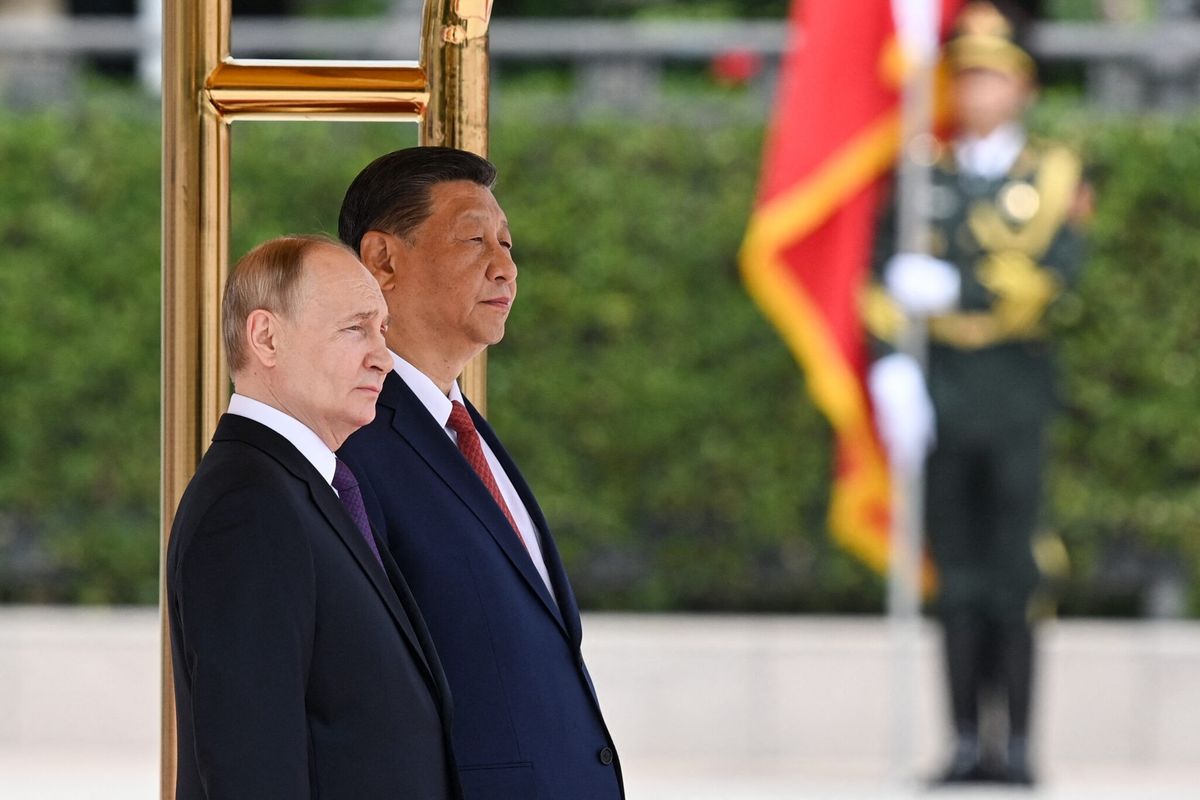

PC: Nations are understandably sensitive to adversary military bases close to their borders. Also Russia and China worry that U.S. missile defense systems near their borders will nullify their strategic nuclear deterrent. If the tables were turned, the United States would feel the same way.

On April 7, 2010, the Russian Federation made a unilateral statement on missile defense, in which it recorded its view that the New START Treaty “may be effective and viable only in conditions where there is no qualitative and quantitative build-up in the missile defense system capabilities of the United States.” The Russian Federation further noted its position that the “extraordinary events” that could justify withdrawal from the Treaty, pursuant to Article XIV, include a build-up in the missile defense system capabilities of the United States that would give rise to a threat to the strategic nuclear forces potential of the Russian Federation.

TCB: What are some ongoing disputes over the deployment of missile defense systems?

PC: Russia does not like the increasing U.S. military presence close to its borders from the Aegis Ashore and Aegis BMD system on U.S. Navy ships.

The dispute with Russia began when the Bush administration called for large, land-based interceptors (similar to those in Alaska and California) to be stationed in Poland with a supporting radar in the Czech Republic. Their purpose was to defend U.S. territory against nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) that Iran didn’t have and still doesn't. In the summer and fall of 2002, the Bush administration approached Poland and the Czech Republic about stationing U.S. missile defense systems on their territory. Naturally, Russia didn’t like this plan. Moscow also felt that this was a betrayal of the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT Treaty), also known as the Moscow Treaty, in which the U.S. had pledged in a Joint Declaration with Russia, signed May 24, 2002, to conduct joint research and development with Russia on missile defense technology and to cooperate jointly with Russia on missile defense for Europe. As author Richard Dean Burns has explained, “Washington’s proposal to establish U.S. Missile Defenses in Europe was neither joint nor cooperative, and was undertaken unilaterally almost before the ink had dried on the Joint Declaration.” (Read page 80 of “The Missile Defense Systems of George W. Bush”)

Similarly, China has objected to possible U.S. deployments of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in Japan and South Korea, and the actual deployment of two THAAD radars in Japan.

TCB: Looking at the THAAD deployment in South Korea, it appears that the U.S. and South Korea will likely go ahead with deployment. What might China and/or North Korea do if this comes to pass?

PC: China and North Korea have many options. For example, China could become more aggressive in the South China Sea. China might establish new military installations on disputed island territory, try to restrict oil drilling, or access to fishing. North Korea could ramp up its offensive missile programs and build and test higher yield nuclear weapons.

TCB: As the technology of missile defense improves, are they likely to become more or less disruptive to disputes between (or among) countries?

PC: As the technology of missile defense improves, they are likely to be more disruptive. As missile defenses improve and their numbers increase, they become more threatening to the adversary. Expanded U.S. missile defense deployments only encourage U.S. adversaries to build more and more offensive weapons to overwhelm those missile defenses, exactly the opposite of what the U.S. would want. For example, current U.S. plans to deploy interceptor missiles in Poland should be paused, that is, placed on hold. And, of course, the Trump administration also should pause the planned expansion of U.S. Aegis missile defenses in Europe.

President Donald Trump has said he would like to improve U.S. relations with Russia. This will be impossible if the U.S. expands missile defenses in Europe. Russian President Vladimir Putin hates U.S. missile defenses in Europe and has given long speeches about how U.S. missile defenses in Europe are upsetting the strategic balance. By simply pausing the deployment of further U.S. missile defenses in Europe, President Trump can show President Putin that he is willing to take a fresh look at what has been one of the greatest obstacles to improved U.S.-Russia relations and continued progress in nuclear arms control. President Trump should put deployment of EPAA’s third phase on hold and assess Russia’s reactions. President Trump has an opportunity to try a new approach with Russia, an opportunity that Trump himself created.