Subscriber+Exclusive Interview — In his new book, By All Means Available: Memoirs of a Life in Intelligence, Special Operations, and Strategy, former Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence and Cipher Brief Expert Dr. Michael G. Vickers shares a lot of the secrets he spent a career protecting.

As Ukraine pushes Russian forces from occupied territory, The Cipher Brief sat down with the former chief U.S. strategist who helped orchestrate something similar against Moscow, albeit far more secretive, some four decades ago.

“[President Vladimir] Putin is not a [President Mikhail] Gorbachev,” explained Vickers, who served as U.S. Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and oversaw what is widely considered the largest covert action in U.S. history, helping mujahideen oust Soviet forces from Afghanistan. “Had there been a leader like Putin in Afghanistan, that war might have dragged on a bit longer, but they would've suffered even more ... and that's certainly what we want to see here.”

To be successful in Ukraine, explained Vickers, a former Green Beret, it “will require additional weapons that we haven't provided right now, F-16s … [as well as] security guarantees, rebuilding Ukraine, [all of which constitute a] much bigger picture than just winning the immediate war.”

In contrast to the once secretive U.S. actions that funneled billions of dollars in arms to Afghan insurgents fighting Soviet occupiers mostly across the 1980s, the Ukraine war — despite the advent of cyber weapons, commercial drones, and private sector involvement — is still more a conventional theatre than Afghanistan, utilizing traditional weaponry, such as artillery and tanks, that allow for more "decisive operations," he explained.

Insurgencies, by contrast, "generally win by a thousand cuts," Vickers added. "This can be shorter, but more intense.”

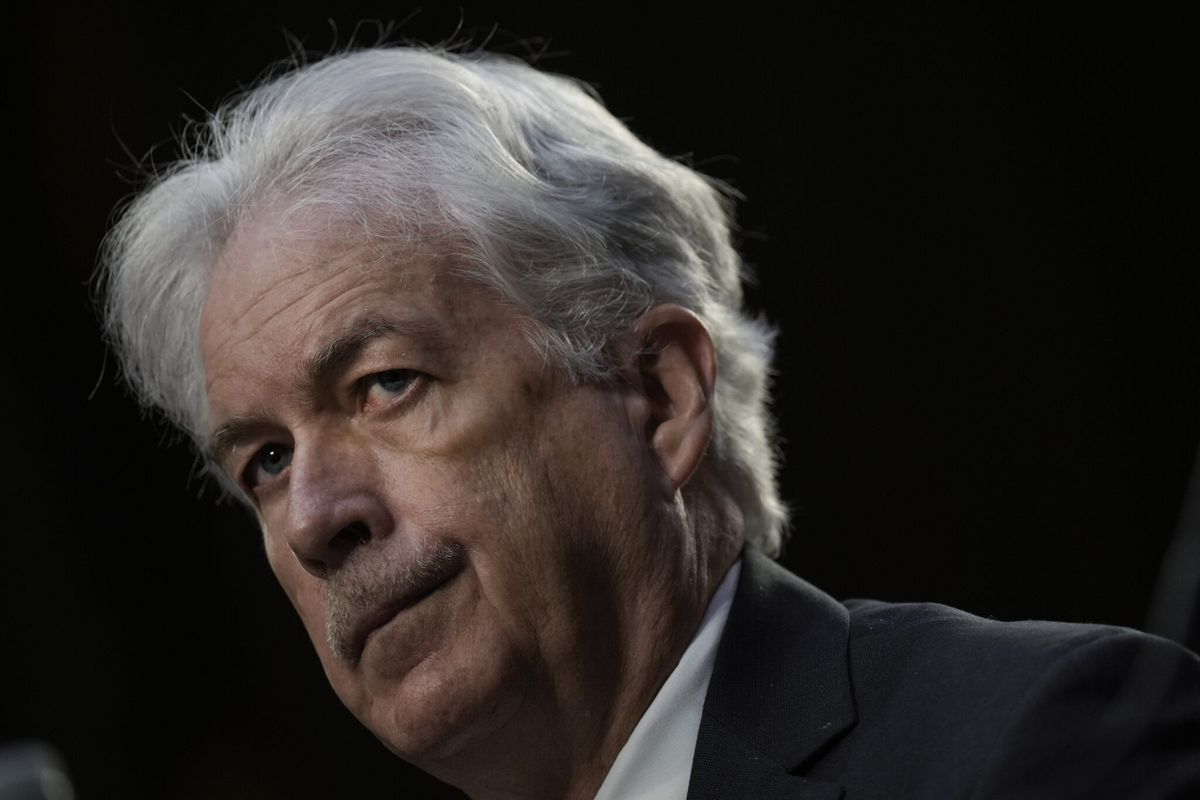

Dr. Michael G. Vickers, Former Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence

Dr. Michael Vickers served as the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence overseeing an $80B Defense Intelligence Enterprise. He played a major policy and planning role in the operation that killed Osama bin Ladin and served as the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations, Low-Intensity Conflict and Interdependent Capabilities. Earlier in his career, he served in the Special Forces and in the CIA’s Clandestine Service.

THE INTERVIEW

The Cipher Brief: The prologue in your book is called "Same Hill, New War." It opens with you describing a 2009 visit to the Afghan-Pakistan border region. How significant was that region to your career overall?

Vickers: It was very significant. The three huge events in my career were the Afghanistan covert-action program that drove the Soviets out of Afghanistan; our campaign in the border region that was conducted mostly with drones and some other instruments to disrupt, dismantle and defeat Al-Qaeda after they had reestablished a sanctuary in the Pakistan border region; and then the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, a little further inland, but close enough for government work. All of them were in that part of the world.

The Cipher Brief: What are the takeaways in terms of these experiences and the others you talk about in the book and the impact they had on your leadership style?

Vickers: The book chronicles my career from a Green Beret - enlisted and then officer - to CIA operations officer to then national security policy maker and intelligence community leader. It spans over four decades. And it covers these three big events, but then a lot of other things too, including hostage rescues, special operations raids, the invasion of Grenada, our response to the Beirut bombings in 1983, trying to stop Iran from getting the bomb, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and Libya, Syria; Ukraine, you name it.

I hope that readers will really see what makes the difference between winning and losing or not doing as well in a lot of cases. In some cases, we win when no one thinks we can win and against extraordinary odds [such as] driving the Soviets out of Afghanistan in the 1980s. And then, we lose wars that by all rights we ought to win. We withdrew from Afghanistan after 20 years and the Taliban took over. How do you explain that?

What I try to argue, is that it's a combination of where we have the right strategies - because we achieve a degree of escalation dominance over our adversary - and we use the right ways and means -the approach we take to our operations - and then having enough and the right kinds of resources to make it work and we achieve the right goals. That sounds simple, but as Prussian general and military theorist Carl Philipp Gottfried von Clausewitz said, the simplest things are very hard in war, whether they're secret wars or open wars.

A second takeaway from the book is not just what we did, but how we did it. To the extent that I was able to, by my agreements with the U.S. government, the book actually explains how we conducted some of these diverse secret operations.

The third takeaway is that individuals really matter. You can have talented people in the military and government and the intelligence community. But when you really get the right constellation, the right authorities, a chain of command that really is aligned to do something… and again, that sounds simpler than it really is. We had our biggest triumphs during the course of my career because we had those stars aligned and a chain of command, that had the same basic idea about how to go about winning.

Want to know what the top minds in cyber are most worried about when it comes to Artificial Intelligence? Save yourself a seat at The Cyber Initiatives Group virtual Summer Summit on Wednesday, June 28th and find out.

The Cipher Brief: Walk us through what some of these missions were like for you. The raid that ultimately killed Osama bin Laden, most of us only heard about that after the fact. You had a very different experience that you talk about in this book. Tell us about what that was like for you professionally and personally.

Vickers: We had been focused on him since 9/11, in terms of trying to kill or capture him. And even before that, in terms of a potential capture operation that never went anywhere. But the trail really went cold after we lost him at Tora Bora during the invasion of Afghanistan. So, it was one of the greatest hunts or intelligence operations in history to string together various pieces of information. First learning the nom de guerre of bin Laden's courier, we tried things that didn't work, along with a strategy that eventually did lead to us finding him. Sometimes, we'd get a glimpse of him but then we'd lose him and couldn't geolocate him because he was very savvy with operational security. So, it was really nine years in the making for that hunt that led us back to the compound.

When I was initially briefed on this at the White House, there were only four of us within DOD who were briefed: Secretary Gates, me, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Mike Mullen, and the Vice Chairman, General James "Hoss" Cartwright. So, we were protecting the biggest secret in Washington, and that was the case for 10 months. We had found him in late August 2010, and I was brought into CIA around Christmastime to start working on options to finish him at the president's direction. We considered special operations raids of various types or airstrikes of various types. We considered doing it with the Pakistanis or without the Pakistanis. And pretty much those operations, those concepts or courses of action that we sketched out were the ones that we ended up considering in the White House. That was exhilarating. It's the first time in my life that I was anxious for Christmas to be over and to really get back to work.

None of my staff knew about this. So I just said, "I'm going to a White House meeting, extraordinary security precautions taken." And I was down in Florida for a vacation with my two young daughters at the time and my wife, and I got called back for a meeting in the White House on Easter Sunday. And my wife asked, "What kind of government makes someone come back on Easter Sunday? What could be so important?" I just took my lumps, and got on a plane and came back.

The night of the raid, once we were helping the President prepare his remarks to the nation, we were finally allowed to talk to our spouses after they started notifying Congressional leaders. I called my wife and I said, "This is why I've been acting so crazy the last 10 months. Just turn on the TV, and I hope you'll forgive me. I'll be home about three in the morning or so." And when I walked outside the White House to go back to CIA - where we had the strategic command and control for the operation - I heard students chanting as I came out of the West Wing saying, "USA, USA," and then, "CIA, CIA," and I thought, I'm never going to hear this again in my life, so I'd better enjoy it for a minute or two, so I did. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

The Cipher Brief: It was interesting to read that that was one of the reasons that you laid out for wanting to write this book.

Mike Vickers: In order to keep secrets with covert operations and intelligence operations, we have a system of oversight where our congressional committees get briefed on those operations, but of necessity, the American people can't, except after the fact in some cases or in lesser detail. I felt it was incumbent on people like me to share what I could about where the government has really done well, where it didn't do so well and why, but as much as I could to say, "Look, they really do work hard on your behalf in these areas." Hopefully that'll be attractive to general readers as they read the book.

The Cipher Brief: Let's talk about one of those other meaningful events: pushing the Russians from Afghanistan, and recap about what that experience was like. And then I want to go fast-forward, and talk about how you feel about pushing Russians out of Ukraine.

Vickers: I've described it as the job of a lifetime because it really was. I had 10 years in the Special Forces, before joining the CIA, and the things I did in the Special Forces were preparing for World War III to help defeat the Soviets if they invaded Europe. If we had World War III in Europe, [I would be] going behind enemy lines and trying to halt their advance, but then [also] try to work with a resistance movement.

I had dreams, actually, as a young Special Forces soldier about how I might be the Lawrence of Arabia of Eastern Europe and liberate them. And I'd studied Russian in college and some Soviet studies and learned about the Sino-Soviet split and I even thought, "Well, maybe it won't be Eastern Europe, maybe the Soviets will invade China and like World War II, I'll help the Chinese against the Soviets.”

Little did I realize that after joining the CIA and some other things, that my big fight against the Soviets would be in Afghanistan, but it would end up working with the Chinese, and helping to liberate Eastern Europe after the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union was collapsing, and the Soviet Army was defeated in Afghanistan. I was in my early 30s at the time. With CIA I'd gone through operational training, and had done the invasion of Grenada, and done a counter-terrorism assignment with Lebanon, but it was nothing compared to Afghanistan. And in Special Forces, for example, an aid attachment is trained to organize, train, equip, and lead in combat 500 to 1500 fighters of a resistance movement. That's why you have several teams. I suddenly found myself with 150,000 fighters. So multiple or orders of magnitude. I felt like a Field Marshal rather than an operator, but an important role, nonetheless.

No one thought we could win. When we took over the job, we had just received a 300% funding increase by Congress that CIA had not asked for. And so this seemed like all the stars were aligned, that we had all these resources. I was getting a chance to fight the main enemy rather than their proxies elsewhere around the world that I'd been spending time on. And so I dug into it with relish. And it involved scaling up the program further. It took a policy shift by President Reagan, that's where the title of the book comes from, to go from just imposing costs on the Soviets for their occupation to trying to defeat them, to actually drive them out by all means available. And I'd loved that line at the time when I was a CIA officer responding to White House queries for a National Security Council review and so I chose it for the title of my book several decades later.

The world changed dramatically in 12 months. We escalated at the same time the Soviets did. A lot of people think of the late Mikhail Gorbachev as a peacemaker, and he was, but his first year he really went for victory in Afghanistan. And so we escalated at the same time he did, and 12 months later after the dust was settled or so, they started thinking about withdrawing, and then the introduction of the Stinger anti-aircraft missile and others definitely convinced them they needed to get out. So, there’s nothing really like it.

Subscriber+Members have access to the exclusive intelligence report from former member of CIA’s Senior Intelligence Service Paul Kolbe as he shares perspectives on Ukrainian drone strikes deep inside Russia, Moscow’s Plan B and NATO’s looming challenge ahead of the Vilnius summit.

The Cipher Brief: What lessons are in this book that you think are particularly applicable to Russia's actions in Ukraine today? Gorbachev and Putin are very different people. We're living in a very different world where the private sector is actually getting more involved in bringing different defensive capabilities to the table. What are you thinking now about Ukraine and pushing Russia out?

Vickers: It’s critical that we defeat Russia in Ukraine. And, what defeat looks like means the Ukrainians are able to recover most, if not all, of their territory, and then [are] able to deter the Russians from further aggression. And so that will require additional weapons that we haven't provided right now, F-16s and other things to help bolster deterrence, security guarantees, rebuilding Ukraine, much bigger picture than just winning the immediate war, as challenging as that will be.

This one is a conventional war. Like the Cold War, most conflicts between superpowers [are] likely to be indirect, where one side may be directly involved [and] the other side [is] working through someone else. [This] helps manage escalation. And, that's the way this war has been. But because it's a conventional war, there's a lot more artillery, there's more tanks. You can have decisive operations in a way that insurgencies [can’t since] you generally win [those] by a thousand cuts and lots of things going on. So this can be shorter, but more intense, obviously.

The Ukrainians have been absolutely heroic, and they've got a lot of things in their favor, besides the national resistance — borders with friendly countries, a lot of countries supporting them — so the conditions for success are there. And the Russian Army has vastly underperformed. US intelligence, it seems, and others way overrated the capabilities of the Russian army.

I'm hopeful about this offensive. I think we've generally done the right thing in supporting the Ukrainians. I don't think we've done it fast enough or at a significant enough scale, and we've denied them some weapons like the Army tactical missile system, which makes no sense to me. But generally, [we are] on the right track, and so we hope all goes well.

As you said, Putin is not a Gorbachev, so he may have to come to a different calculus than a Gorbachev would have. Had there been a leader like Putin in Afghanistan, that war might have dragged on a bit longer, but they would've suffered even more at the same time, and that's certainly what we want to see here.

I think the reason we got into this war in the first place, besides Putin's grandiose imperial designs to recreate at least part of the Russian Empire with Ukraine being a key part of that, is that we failed to deter him over a significant period of time. Beginning in 2014, I made several trips to Ukraine — 2014 and 2015 after the Russians seized Crimea and then intervened covertly and overtly in the Donbas, Eastern Ukraine. We weren't providing lethal assistance. The thought was there's no way the Ukrainians could win. The Russians would easily win, and that's generally a mistake. You still want to impose as much cost as you can on an adversary, so they don't do it again, even if they are to prevail at the end of the day, and you might change their calculus.

Russians intervened in Syria. We were backing the Syrian opposition. The Iranians, Hezbollah and Russians were backing Assad, and we kind of gave them a free pass again. And so, they slowly turned the war with Iranians and others in favor of the Assad regime. I talk about that in the book, too.

Then, there's the interference in the US presidential election, and then there's the signals we sent to Russia that before the invasion that we might not do much. And it's all that undermined deterrence. Just being candid about it. I've served Democratic and Republican administrations at very high level, so I just try to call up the way I see it. But now we're doing better, and so I wish the administration all good fortune and the Ukrainians in particular.

Some people will argue that we should prioritize China over Europe and Russia, Ukraine. [China and Russia] are allied and Europe is critically important to us. I argue our best China strategy and the near term is to defeat Russia. And then in the longer term, you have to beat the Chinese technologically and lots of other things, but that's the longer term.

The Cipher Brief: What do you think are the most likely scenarios that we might see play out for ending the war? And then, how do you predict that Russia's involvement on the world stage may change in the next three to five years, a relatively short timeframe?

Vickers: The way Russia has ended most of these conflicts recently is just to try to freeze them in some way. And so you may end up with something more like a Korean armistice than you do peace negotiations. I certainly don't believe as long as you have a Putin or Putin-like regime you'll get war crime accountability or reparations or anything like that from the Russians. So the most you can achieve is if you have victories on the battlefield to then, from our perspective, sort of secure them in place and then make sure to do the things that are necessary to make sure that it's much more difficult to invade in the future, to bolster deterrence in Ukraine. That's a combination of security guarantees, military and other assistance and economic assistance, to make them attractive.

This has been a strategic disaster for Russia. Had they won and won easily, their options would've been much greater. What they might do next, then, might be just achieving coercive effects on Europe, rather than a military invasion of the Baltic states or something like that. But now, they will spend years trying to rebuild and who knows how the Russian politics will shake out in the longer term.

But if you were a Russian nationalist just looking at this, you'd have to be appalled at how much Russian power has been destroyed, and so they're going to become even more subservient, I think, to China over the longer period than they otherwise would've been, had they played their cards right.

One of the key principles and strategies, as I said, is to try to build power, not to deplete it. And so sometimes you have to use power to build it, but other times when you use it too much, you actually end up depleting it. And so that's a tough thing to get, but you kind of judge leaders at the end: where are we? [Are we] better off than we were before? And that applies to strategy as well, and Russia's clearly not going to be better off coming out of this.

It’s not just for the President anymore. Cipher Brief Subscriber+Members have access to their own Open Source Daily Brief, keeping you up to date on global events impacting national security. It pays to be a Subscriber+Member.

The Cipher Brief: Part 4 of your book is called "Fighting on Multiple Fronts," and it reminds us that this is not just a China, Russia, US world that we're living in. There are a number of things going on that demand attention in order to ensure future US national security. Among them are some interesting things that aren't in the headlines every day, like counter proliferation, counter macro insurgency, the battle for the Middle East, crisis and change in defense intelligence. Talk to us about how you came to collect these particular topics as the things impacting US national security.

Vickers: I tried to write the book in five parts: what I did to prepare for when things really got big for me, which was Afghanistan and the CIA, so I lumped some CIA and special forces stuff together there; and then the big events, so the wars with Al-Qaeda and the Bin Laden raid. But that wasn't all, and so what I wanted to convey as a senior policymaker and intelligence leader [is] you deal with global things. And so, while Al-Qaeda was job one for me, stopping Iran from getting the bomb was wasn't too far behind. And then there were things right on our doorstep, like the cartels getting very, very powerful in Mexico. Instead of just being a narcotics problem, it was becoming a national security threat, both to Mexico and to us. And so what those operations look like and where we succeed and failed, I think it was important to try to tell the reader, too.

And then other battles in the Middle East beyond that with the global Jihadists, so Syria, Libya, Yemen against the Houthis, et cetera, how the Middle East was being reshaped by Arab Spring and by these wars, I think was another important part of the story. And so I tried to convey all that, and multiple fronts seemed to be a good way to describe it. There were of course multiple fronts with Al-Qaeda as well, but these were different kinds of operations in the war. And then with Ukraine, Russia, Ukraine, and the rise of great power competition being the segue into the new Cold War in which we find ourselves now, which is the last part of the book, along with lessons learned. I do see it as not just an appendage, but as policymakers having to deal with more than one thing.

The Cipher Brief: Part four of the book includes a story about your retirement ceremony. This one included a ceremony hosted by the Secretary of Defense, a personal letter from President Obama, a ceremony at CIA, and other interesting things. What struck me was that you said your one regret was that you wish you could start your career over again. Going back to what you said a minute ago about the importance of individuals, what would you say to a freshly minted Green Beret or brand new CIA case officer who's just about to enter this world?

Vickers: We talked about this earlier, but I wrote the book for three reasons. The first was what I felt was my duty to history, having participated in these events or played a central role in some of them, and then being able to tell a story that others haven't heard. And then, we talked about the other one, about duty to the American people to explain the secret world in a little more detail. But the third reason was really aimed at what you just said, which is the future special operators, intelligence officers, and national security strategists who are going to carry on the fight. And I wanted to pass on what I learned to them because I am worried about where we are right now as a country, and the challenges are growing. That's why in my chapter on winning the new Cold War, the first thing I talk about is rebuilding the domestic strengths of our power. Because if we can do that, we can handle the other problems. If we can't do that, we're going to really struggle in the world.

And that's a view, I might add, that's shared by a lot of my former contemporaries. General Jim Mattis, who became our Secretary of Defense, and others have the same view about the primacy of trying to get our domestic house in order. Then that's not something that people like me or Jim Mattis or others can do. We can just advocate for it, and we hope our political leaders and business leaders and others and other moral leaders will take up the cudgel and do that, but that that's absolutely critical.

To your point about advising young Green Berets or CIA officers, I was really blessed in my life to do what I was not just passionate about, but eventually became good enough at. It's one thing to be passionate... I was passionate about becoming a pro quarterback or a baseball player, and I realized my passions were far greater than my abilities at some point. I went and decided that maybe being a Green Beret is the next best thing, and it turned out to be a way better thing. But to me, you're blessed when you get to do something you really enjoy and you feel like you're making a contribution. And so I've certainly felt that at various stages of my career.

The Cipher Brief: What comes next for Mike Vickers?

Vickers: I might try writing a few more books. I just want to make the biggest contribution I can. I've done talks from time to time at CIA and elsewhere trying to pass on some things or help them with current problems. I don't have that many years left to be really productive, but I want to make them count as much as I can.

The Cipher Brief: Would you be willing to go back into government if that were an option in the future?

Vickers: I would for the right job. I never wanted a job just for a job sake, though. I've always felt I've been blessed by having the right job at the right time when it could really make a difference. Something that I could do well, but also the leaders above me wanted me to do something that I had the skills to do rather than just manage this place and pass it on to the next person. I never really enjoyed a job like that. And there's not a lot left that I would be qualified for, but if I had the chance and the President felt I could make a difference, then yes. You never say no.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspectives and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business

The Cipher Brief may earn a small commission on purchases made via links.