The Fund For Peace’s 2017 Fragile States Index paints an alarming, but justified, picture of Turkey: it is declining dramatically in most areas measured by the index. Turkey saw drops in security, fractionalized elites, group grievances, human rights, and refugees and internally displaced persons. Only the last, refugees and IDPs, may be challenged, as Turkey has done well stabilizing a huge population out of Syria. In the other areas, though, the bad grades are warranted.

Overall, Turkey dropped by 3.5 points in this latest survey from 2016, one of the three largest declines in the global inventory, and the largest drop for Turkey in over half a decade. These indicators suggest serious problems in Turkey’s social, economic, political, and security situation that deserve further study, given the importance of this country: 18th largest economy in the world and overall strongest state in the broader Middle East.

Recent economic indicators point to a considerable weakening of the Turkish economy, loss of confidence by investors, and growing financial risks beyond the concerns of a generally restrained IMF Country Report issued in early 2017. Some reasons for the significant drop in economic indicators and expectations are the rise in geopolitical risk stemming from the regional security situation; the impact on foreign states, investors, and loan sources of internal political developments; and long-term political and legal challenges to Turkey's economic performance and human capital. Taken together these factors significantly impact performance and enhance risk.

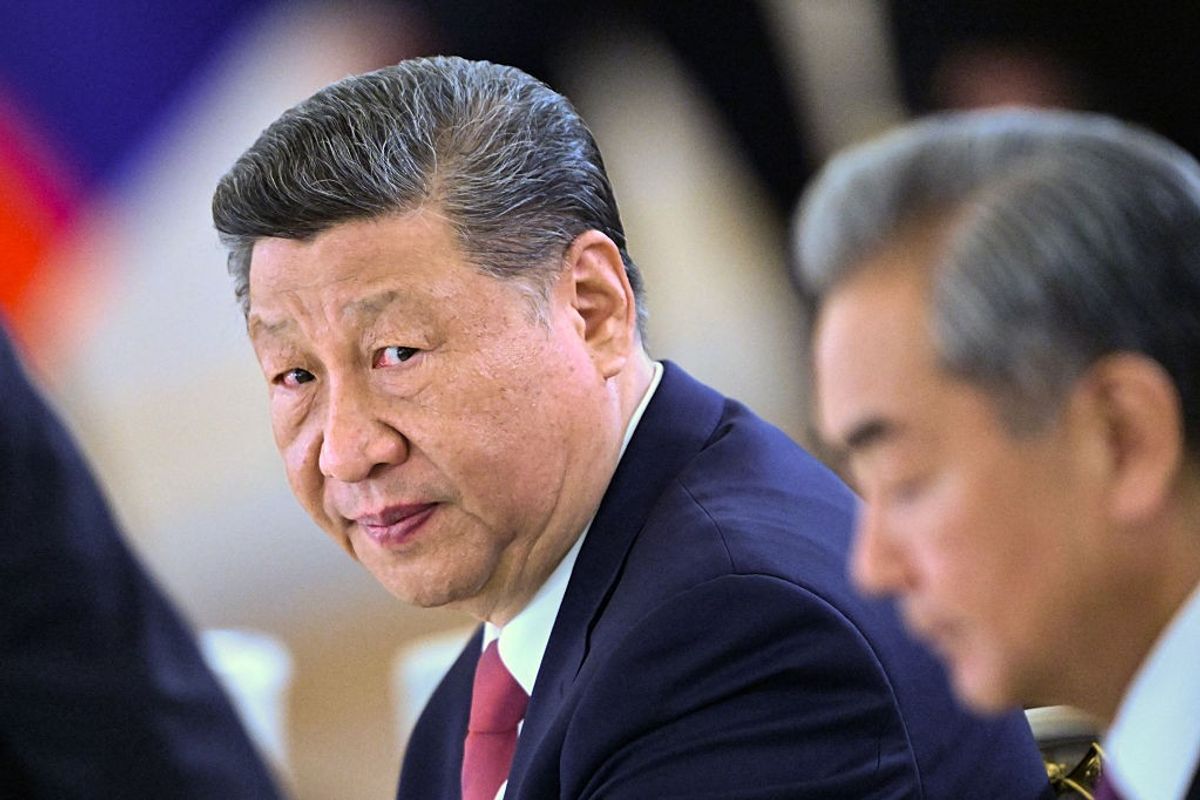

The deterioration of security in and around Turkey has been dramatic over the past three years, with millions of Syrian refugees housed in Turkey, the rise of ISIS and its campaign against Turkey that reached a peak in 2016, the outbreak of a new and more violent phase of Turkey's 30-year war against the Kurdish PKK insurgency, and growing Syrian-Iranian-Russian cooperation, which includes working against Turkey's objectives in the Syrian civil war.

Finally, the last nine months have seen a direct and costly Turkish ground intervention into northern Syria and a serious dispute with the U.S. over policy towards Syria, especially the use by the U.S. of Syrian Kurdish forces from the PYD, a Syrian Kurdish offshoot of the PKK. Russia's more aggressive behavior to Turkey's north from the Balkans through the Black Sea to the Caucasus, and Iran's regional aspirations, which President Recep Tayyip Erdogan termed “Persian expansionism” at the Atlantic Council's April 2017 Istanbul Energy Summit, further darken regional security prospects.

By mid-May, the security threats to Turkey had receded somewhat. It continued its limited rapprochement with Russia, which included the Astana Syrian ceasefire effort. This has partially restored Ankara’s relationship with Moscow, which was affected by the shoot-down of a Russian fighter in 2015. Moreover, Erdogan and U.S. President Donald Trump, in their first meeting May 16, at least papered over their divergent policies towards Syria and ISIS. The deepening engagement by the U.S. in Middle East security and specifically on efforts to contain Iran – manifest in Trump's trip to Saudi Arabia and Israel – should deepen cooperation between Washington and Ankara, and calm the region.

On the other hand, new U.S. engagement against Iran could generate clashes or even a regional conflict. The security situation in and around Turkey has already almost halved Turkey's tourism business, a critically important generator of hard currency, since the 2015 peak. A significant regional conflict could dry up all tourism and potentially drive up oil prices, crippling Turkey, given its almost total dependence on oil and gas imports, the latter mainly from unfriendly Russia and Iran.

More generally, the ongoing diplomatic dispute between Turkey and the EU states could sap the appetite of EU NATO allies to come once again to Turkey's defense (European NATO state militaries have deployed to Turkey three times since 1990 in response to its appeals to the organization). While relations with the U.S. are seemingly much more stable since the White House visit, beneath the surface in Washington, particularly in military circles, there is deep skepticism about Turkey's reliability as an ally, dating all the way back to 2003, when it refused to allow the U.S. to strike Iraq from Turkey.

The domestic political situation also threatens Turkey's relations with outside investors, financiers, and business partners, particularly Europeans. Turkey's economic miracle over the past two decades is largely due to its Customs Union with the EU that has led to the construction of some 4,000 foreign – largely EU –factories and service centers just south of Istanbul. Erdogan's pro-export policies have also benefited mid-sized export firms, many from his political heartland in central Anatolia. Worsening diplomatic relations with the EU over Erdogan's ever more authoritarian policies, including politicization of the court system, are already affecting Turkey's attractiveness for many European entrepreneurs and financiers. A dramatic break with the EU, such as a halt to EU membership talks, perhaps due to Erdogan's interest in restoring the death penalty, would significantly chill outside interest in Turkey as a business partner.

Finally, Erdogan's ever more successful campaign against Turkey's diverse institutional landscape and his assault on personal liberties, freedom of expression, and the media, could discourage many of his more productive workers. Turkey, unlike Russia or Brazil, cannot base its economy on minerals or hydrocarbons extraction; nor, like China, does Turkey have the enormous investment funds, mercantilist economic policies, or huge domestic consumer market to sustain its economic growth.

Like Israel and Singapore, Turkey has had to rely on the competitiveness of its more productive human capital to sustain economic growth in the modern world. However, many of Erdogan’s policies, from politicizing courts to banning Wikipedia, strip these workers and their enterprises of the tools they need to prosper. Moreover, the oppressive political climate and Erdogan's efforts against Turkey's Western orientation in favor of a more Islamic Eastern orientation are deeply troubling to a high percentage of Turkey's entrepreneurial and knowledge elite. In most cases, they can find employment outside of Turkey. This kind of brain drain could continue to sap competitiveness.