OPINION — It appears that the U.S. Intelligence Community scored a success in warning senior leaders that Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin was planning some sort of armed action against the Russian military. We would not have known that had not people inside the U.S. Government shared this with the press. Often, the Intelligence Community simply absorbs slings and arrows when accused of an intelligence miss or failure; protecting sources and methods is more important than scoring points.

Prior to this admission or exposure, I’m not sure which, press stories had suggested that U.S. leaders were caught off guard, forcing Secretary of State Tony Blinken and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley to cancel planned trips. As it turns out, not exactly.

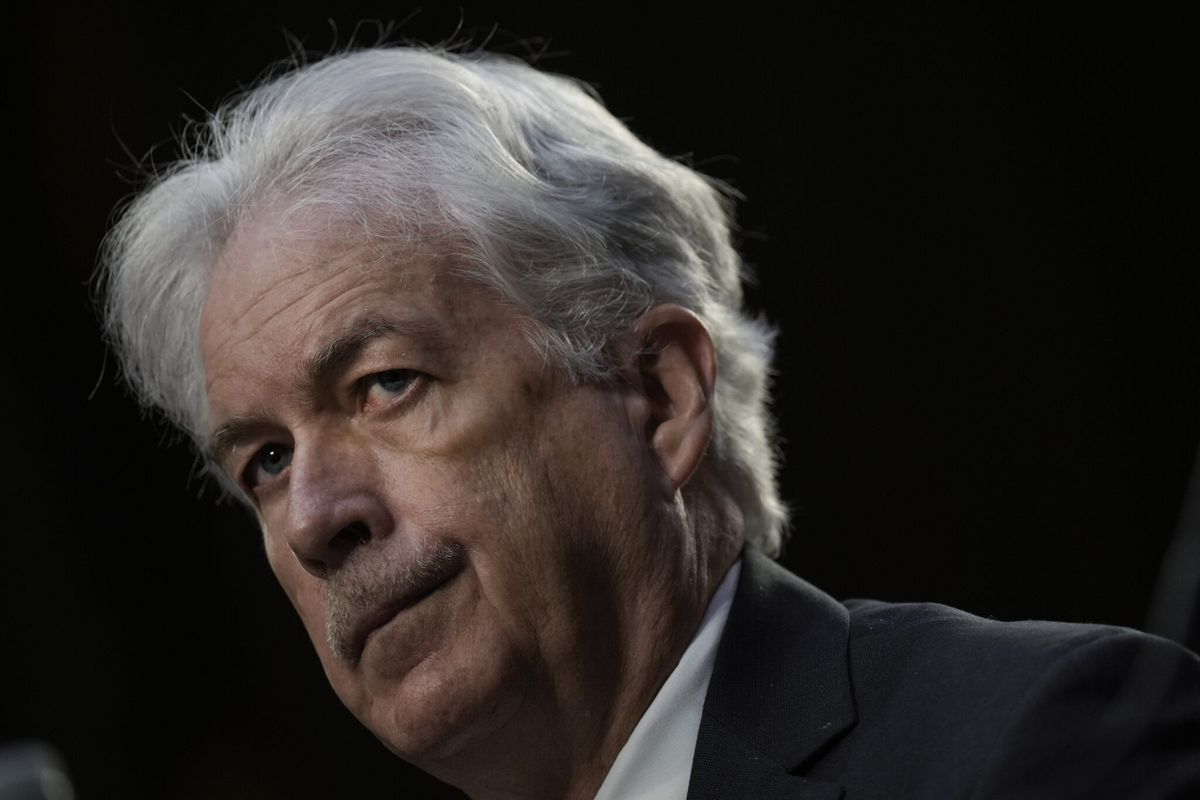

While I have no knowledge of discussions inside the Intelligence Community or the Administration about what transpired, as a former intelligence official who delivered such warnings to Presidents, senior military officers, and Congressional leaders, I hope to explain some of the challenges of conducting analysis in such circumstances and how to scope potential implications that undoubtedly will continue to unfold.

Intelligence is Secret for a Reason

The intelligence about Prigozhin’s plans appears to have been very sensitive and tightly-held, as indicated by an intelligence briefing to the top Congressional leaders, known as the Gang of 8. If some Administration folks were caught off guard, it probably was because they didn’t have a need to know. As to the cancelation of trips by senior officials, in my experience, such trips are not canceled in advance of a still-secret move by an adversary; that would be known as “a tell” or, more simply put, “dumb.”

Good Analysis is Hard

Let’s just be clear: none of the pundits or experts that I know of, even those closely watching the building tensions between Prigozhin and Russian military leadership foresaw Prigozhin’s full-out mutiny. This should remind us that a little analytic humility is in order. For those sitting outside the intelligence and policy communities’ circle of trust, we often possess much of the same information as gathered by the Intelligence Community, but exquisite intelligence collection remains vital and, hopefully remains, unknown to those without a clearance. Listening to some of the punditry about who did what, why, and what’s next is interesting, but in this circumstance, I would not bank on any of it.

Want to know what the top minds in cyber are most worried about right now? Save yourself a seat at The Cyber Initiatives Group virtual Summer Summit on Wednesday, June 28th.

There is a lot that we still do not understand, and some information about which we may never know. At this point, I would advise policymakers to ask for what is known, the identification of areas of risk and opportunities, the factors driving decision-making by the various players (Putin, Prigozhin, elites, average soldiers, Russians, Russian client states and partners, etc.), the indicators that might reveal the direction of events, and some scenario-based assessments. This is not the time for “an answer” on whether this spells the end of Putin.

Analytic humility must extend to everyone looking at Russia, or any other complex system for that matter. No one is immune to surprise given inherent biases, logical fallacies, information gaps, and the inability to truly anticipate what another human being will do. This is particularly true regarding an opaque interpersonal and decision-making system like Russia’s. Many outside experts missed Putin’s invasion and Prigozhin’s mutiny because logically it made no sense to them, something Russian expert Fiona Hill has called, “no he wouldn’t.” Intelligence analysts, for their part, appear to not have fully played out the cumulative and interconnected effects of Russia’s military shortcomings, its corruption, an invasion plan built on faulty assumptions, and the ability of Ukraine’s military and public to stymie Russia’s invasion.

The Intelligence Community excels at strategic warning, for example pointing out that conditions are ripe for a coup. But pinpointing exactly when something is going to happen or the specific parameters of an activity, tactical warning, is much more difficult and often not possible. I do not know, but I suspect that no one foresaw that Prigozhin would try to occupy the most important military logistics hub in Russia — Rostov-on-Don — or at least launch his march on Moscow. Why? Tactical warning requires access to accurate and detailed plans as well as the knowledge that a leader has decided when exactly he or she will execute those plans. If tactical warning was lacking in this case, and perhaps it was not, the possible reasons would include: the Intelligence Community was unable to get their hands on such plans, Prigozhin’s decision to launch was not detected or acquired, Prigozhin kept detailed plans to himself meaning there were no plans to steal, and/or he was making up at least part of the plan on the fly.

We Should Expect Some Surprises

Questions about a leader’s, or any person’s, intent are the hardest to answer. To truly know would require access to that person’s thoughts. When does the Tunisian fruit-seller who set off the so-called Arab Spring decide to self-immolate; when do parents allow their children to join demonstrations or join themselves; when will a leader decide that they must launch an invasion to achieve their objectives and legacy?

Analysts make such judgments based on the current context, what is known about the decider’s priorities and redlines, their past behavior, and observed indicators. Deep experience and expertise go a long way in making accurate assessments about intent. But the arithmetic that informs a leader’s actions is probably never fully understood and is rarely static, instead shifting with evolving circumstances and options. Analysis about intentions will always be a human endeavor, both in the observed and the observer, and therefore an art rather than a science. Humans are complicated.

With this in mind, I expected some surprise as the effects of the Prigozhin mutiny continue to reverberate. What led Prigozhin to go from diatribe to mutiny to sudden surrender? What led to Putin’s apparent surprise, emotional charge of treason, and then abrupt capitulation? Given that none of those involved —Prigozhin, Putin, elites, the Russian military, Wagner soldiers and supporters — can be satisfied with the outcome, more surprise is likely.

Thinking Through What’s Next

Prigozhin’s mutiny shattered myths about Putin’s invincibility, his justification for the war, his toughness, and the Russian military and intelligence services capability to protect the motherland. Putin is undoubtedly weaker as a result, but what this means for Putin and his goals is less clear.

One of the reasons for this lack of clarity is that we do not know to what degree the shattering of these myths has been absorbed by or matters to the individuals and entities that will determine the future. Nor can we gauge with any certainty what actions they will take. It’s one thing for people to be shocked, but it is quite another to do something about it.

Although we lack a crystal ball, we can at least begin to think through potential implications by focusing on the outstanding issues that must be resolved, the context of the dilemmas facing Putin, and how various stakeholders might be viewing Putin’s humiliation.

Unresolved issues: How the following questions are resolved will be key to outcomes, but some will not be resolved quickly or cleanly, creating more opportunity for surprise: What will happen to Wagner as Putin’s most important foreign policy tool? Will Prigozhin be trusted to continue in some capacity, neutered, or killed? Will he attempt to control some Wagner activities independent of Kremlin? What has and will happen to the pardoned Wagnerites who participated in the mutiny? What actions will Putin take to reassert his control, authority, and stature? Can the Russian military avoid significant individual or unit insubordination or defections?

Dilemmas: Putin was and probably is still weighing a long list of factors and potential ramifications for how he should handle this crisis, some of which we probably do not know. Here are a few that I think Putin considered, in no particular order:

- Maintaining Wagner as one of the most important instruments of Russian influence. Wagner’s importance in Ukraine is diminished and limited. But it remains, more importantly, one of the most important means of projecting Russian power and influence. The Kremlin uses Wagner’s military and influence capabilities to create essentially client states in the Middle East and Africa that are beholden to Russia. It’s global disinformation capabilities, used to try to influence the 2016 U.S. election, are diminished but remain potent in the Global South in particular.

- Avoiding undermining the war effort and potentially setting in motion the destruction of the army, a coup, or a revolution akin to 1917. Putin warned in his address to the nation on Saturday morning (24 June), that the mutiny threatened to divide the nation and seemed to indicate that the mutiny needed to end soon and, if possible, without spilling Russian blood.

- Ensuring that Prigozhin ceased to pose a threat. The betrayal must have hit Putin hard; he has never faced such a challenge, and a public one at that. Putin must ensure that Prigozhin can never pose a military threat and will never denigrate the Russian military or him personally again. This may mean that Prigozhin must die. But we do not know the extent of their symbiotic relationship and what levers each of them has over the other.

- Limiting the damage to his stature and authority based on how he resolved this crisis; Putin surely felt the gaze of Russians, clients, partners, and adversaries. Putin will have to act to restore his authority domestically, in the war on Ukraine, and with his foreign partners. It is not surprising that Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister traveled to Beijing today, undoubtedly to assure the Chinese that Putin is firmly in charge.

Stakeholders: In considering strategic implications, we can drill down on the constituencies that matter most to US interests. This last question of how the damage to his stature and authority plays out is instrumental. Three constituencies are probably most important, and each is hardly monolithic: Russian soldiers, Russia’s foreign client states and partners, political and military elites.

Russian military: Wagner’s demise is not likely to affect the war in Ukraine given its diminished and limited role since Bakhmut. The psychological effects on the Russian soldiers’ will to fight has more potential, although it will be hard to assign causality. Surely Prigozhin’s message about the venality of their military leaders has been heard by and resonates with many soldiers. Potential effects will diminish over time if Putin is successful in muzzling. Hints of a mutiny effect on the will to fight might be detected in milbloggers’ posts, military units creating complaint videos (as was the case earlier in the war), and intercepted communications between families and soldiers. Russian military leaders have been more effective in using a combination of improved supplies, coercion, and threats to keep soldiers in line. I suspect Putin will insist they will double down in the wake of the mutiny.

Client and Partner States: Putin’s weakened status is likely to have geopolitical implications. Surely Russia’s client states and partners were alarmed during the mutiny and will be engaged in Kremlinology to discern the degree of Putin’s vulnerability. Countries that leverage wheeling and dealing with Russia to balance their relations with the US (and sometimes China) ultimately will find a weakened Russia is not nearly as helpful. States dependent on Russia will start to hedge more. For example, we could see South Africa weaseling out of hosting Putin for the BRICS summit in August, Syria leaning closer to Saudi Arabia, Egypt taking less risks in buying big tickets arms from Russia that could jeopardize US support, and Venezuela shifting more weight to Iran and China or perhaps the US if we lift restrictions.

Wagner: The potential collapse of Wagner could be the most consequential and beneficial development resulting from the mutiny. This is not inevitable nor would it happen overnight, but there is strong potential, particularly if the US and allies actively work to achieve this. Russia’s influence in the Middle East and Africa would diminish considerably if Putin is unable to use Wagner resources as a forceful instrument of his foreign policy. It is not surprising that today (Sunday, 25 June), Russian warplanes carried out the most deadly airstrikes of 2023 in Syria, hitting multiple targets across rebel-controlled Idlib province, including a crowded market place. I hazard a guess that this was a message from Moscow to its client, Bashar al Asad, “we’re still here!” Eliminating Wagner would cripple Russia’s ability to create instability in Africa, to buttress and control corrupt leaders, and to exploit the resource wealth of these countries.

Elites: Although Putin’s future relies on support from elites, this group is not likely to stage a coup or threaten Putin’s rule in the near term. Putin has just bought the loyalty of the military by picking them over Prigozhin, and the other elites appear to lack the power to challenge him directly. Further signs of weakness or strategic failure could quickly change this, however. And our lack of true understanding of Putin’s byzantine world makes us vulnerable to surprise here as well.

Popular Support: The public, for now, is not a main player in outcomes. The displays of support in Rostov-on-Don, a military town, are not likely to spread to other areas, both because the population elsewhere is more indifferent to the effects of the war and cowed. But Putin’s concern about a color revolution in Russia makes public opinion a factor in his decision-making, perhaps leading to a further crackdown on freedom of expression and signs of dissent. An indicator will be whether people who expressed support for Wagner during the mutiny are detained.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspectives and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business