The signs emerging from Washington confirm that the military option is still very much on the table. There is now a breathing space while the Winter Olympics play out at Pyeongchang in South Korea followed by the Paralympics which conclude on 18th March. Shortly thereafter, the annual joint military exercises between South Korea and the United States are scheduled. These exercises, known as Key Resolve and Foal Eagle, always infuriate North Korea and may even lead to concerns in Pyongyang that they could be used as cover for an actual military strike.

For the South Korean government, the exercises threaten to undo what they see as potential gains from the Winter Olympics where the two Koreas will march together under one flag and field a joint ice hockey team. It is reasonable to suppose that they will hope to make sufficient diplomatic progress during the Games themselves to persuade Washington to further delay the exercises or even to scale them back to desk-top level. For Seoul, there will be a difficult balance to strike: to avoid damaging the progress with North Korea while not leading Washington to conclude that their ally is unreliable.

The truth is that the government of President Moon Jae-in is fundamentally out of sympathy with the present U.S. administration. Moon’s key advisers all spent their formative years opposing the authoritarian South Korean governments of the 1980s. Those were years during which left-wing student activists regarded North Korea under the legendary Kim Il-sung as a beacon of socialist values.

Later, the advisers were all strong advocates of the “Sunshine Policy” of former Presidents Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003) and Roh Moo-lyun (2003-8) and they (rightly or wrongly) blame the United States for bringing the Sunshine Policy to a premature end.

Moon’s key adviser on North Korean affairs is Professor Moon Chung-in. He was an architect of the Sunshine Policy and a special delegate at the two Korean summits held in Pyongyang in 2000 and 2007. In a June 2017 speech in Washington, he said, “If North Korea halts its nuclear and missile activities, we might discuss a reduction of joint military exercises with the U.S. and the US strategic weaponry deployed on the Korean Peninsula.” He later commented that “a shattering of the South Korea-U.S. alliance would not mean war.”

Criticism of him by conservatives led the left-leaning newspaper Hankyoreh to ask “Where do things end if South Korea continues to allow itself to be dragged around by the U.S. without finding its own balance?”

Equally influential is Lim Jong-seok, the Chief Presidential Secretary. He is a former student organiser who, after a year on the run from justice, spent over 3 years in prison for facilitating an unauthorised visit to North Korea by the female activist Lim Su-kyung, from which North Korea derived significant propaganda benefit. It was an incident reminiscent of Jane Fonda’s visit to North Vietnam in 1972.

The head of the National Intelligence Service (NIS) Suh Hoon also has extensive experience of North Korea. As a serving NIS officer, he too was involved in the 2000 and 2007 summits but more importantly he spent two years in the North during preparations for building the light-water reactor at Sinpo in 1997-8 under an international agreement. The project was cancelled by the U.S. in 2002.

A quick scan of Korean conservative websites and blogs will suggest that Moon’s advisers are communist sympathisers. More likely, they are genuinely convinced that inter-Korean relations are the solution to the current crisis. They are certainly worried that a war on the peninsula, whether provoked by Pyongyang or Washington, would spell disaster. Even a purely conventional war would likely cost tens of thousands of lives and inflict considerable damage on the South Korean capital. They regard this as an unthinkable price and it is reasonable to conclude that they will seek to prevent it happening. But how? I think they have three options.

The first is to demonstrate to Washington that the inter-Korean dialogue is delivering real dividends. Certainly these will fall short of denuclearising North Korea but the aim (which the North would exploit for its own ends) would be to put Washington in the uncomfortable position of having to sabotage ongoing and apparently promising negotiations in order to stage a military strike.

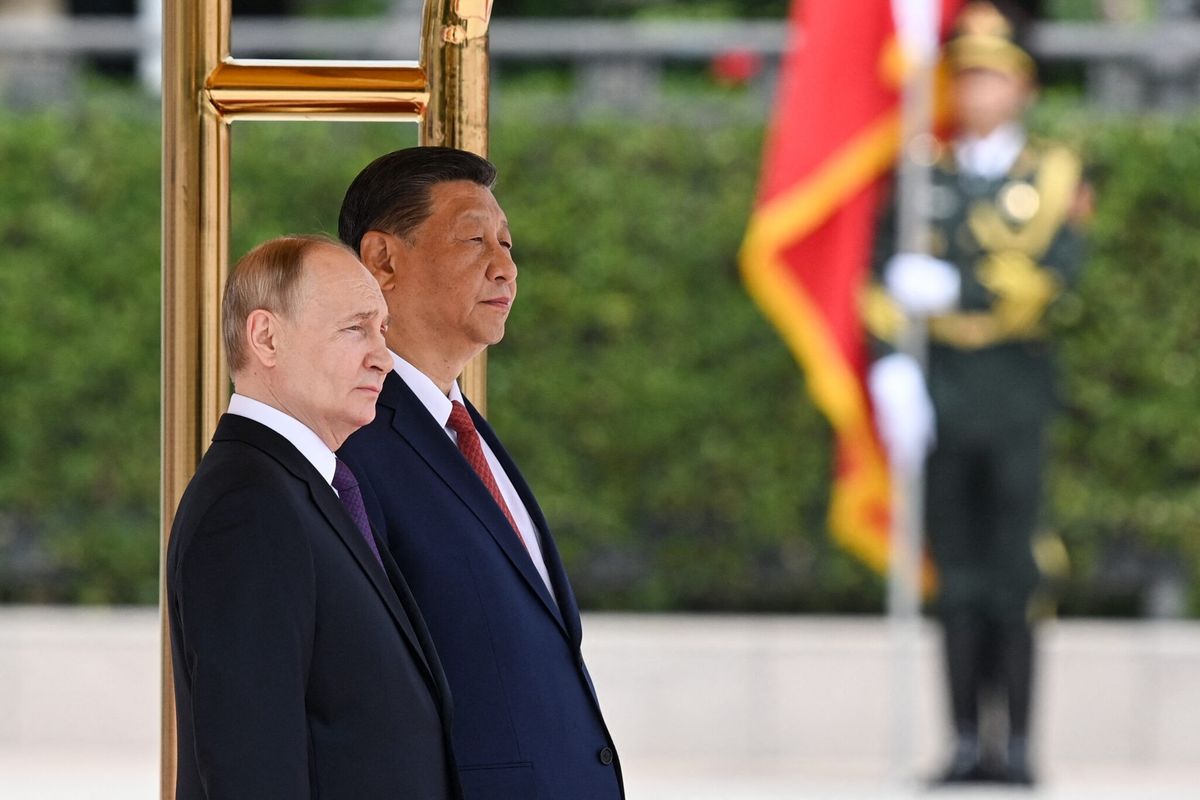

The second and linked possibility would be for the two Koreas to involve China in the negotiations. China would be seen to take a “tough stance” towards the North’s nuclear programme whilst positioning itself as the guarantor of the inter-Korean process. The message from Beijing to Washington would be, “Don’t worry; we’ve got this under control”. In this case, China would oppose any U.S. military intervention and even threaten to counter it.

And the third option, which the South Koreans would hope to avoid, would be to refuse to allow South Korean forces to be involved in any US attack. By so doing they would significantly increase the risks to US troops as well as U.S. casualty levels. The fact that South Korea will inevitably have prior warning of U.S. military intentions gives Seoul a potent but blunt lever to prevent a war.

Washington is currently acting as if it is holding all the cards and can decide when and how to play them. However, all the other players have cards too. North Korea knows how to exploit the concerns, sincerity and perhaps even naivety of the Moon government. This is a bad time for Washington to delay the appointment of a new ambassador to Seoul because South Korea and Washington both need good advice at this critical moment. The only winners from U.S.-South Korean disunity would be China and North Korea.