Asked if there were any restraints on his global powers, [President Trump] answered: “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.”

“I don’t need international law."

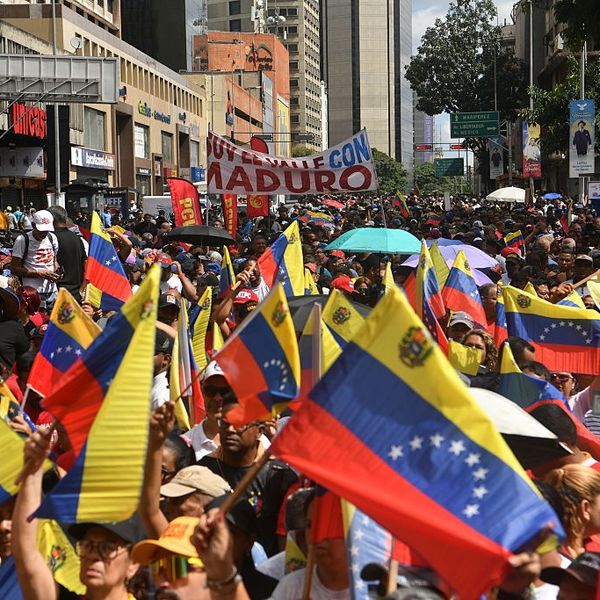

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE — Nicholas Maduro’s fate seems sealed: he will stand trial for numerous violations of federal criminal long-arm statutes and very likely spend decades as an inmate in the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

How this U.S. military operation that resulted in his apprehension is legally characterized has and will continue to be a topic of debate and controversy. Central to this debate have been two critically significant international law issues. First, was the operation conducted to apprehend him a violation of the Charter of the United Nations? Second, did that operation trigger applicability of the law of armed conflict?

The Trump administration has invoked the memory of General Manuel Noriega’s apprehension following the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama, Operation Just Cause, in support of its assertion that the raid into Venezuela must be understood as nothing more than a law enforcement operation. But this reflects an invalid conflation between a law enforcement objective with a law enforcement operation.

Suggesting Operation Just Cause supports the assertion that this raid was anything other than an international armed conflict reflects a patently false analogy. Nonetheless, if - contrary to the President’s dismissal of international law quoted above – international law still means something for the United States - what happened in Panama and to General Noriega after his capture does have precedential value, so long as it is properly understood.

Parallels with the Noriega case?

Maduro was taken into U.S. custody 36 years to the day after General Manuel Noriega was taken into U.S. custody in Panama. Like Maduro, Noriega was the de facto leader of his nation. Like Maduro, the U.S. did not consider him the legitimate leader of his country due to his actions that led to nullifying a resounding election defeat of his hand-picked presidential candidate by an opposition candidate (in Panama’s case, Guillermo Endara).

Like Maduro, Noriega was under federal criminal indictment for narco-trafficking offenses. Like Maduro, that indictment had been pending several years. Like Maduro, Noriega was the commander of his nation’s military forces (in his case, the Panamanian Defense Forces, or PDF).

Like Maduro, his apprehension was the outcome of a U.S. military attack. Like Maduro, once he was captured, he was immediately transferred to the custody of U.S. law enforcement personnel and transported to the United States for his first appearance as a criminal defendant. And now we know that Maduro, like Noriega, immediately demanded prisoner of war status and immediate repatriation.

It is therefore unsurprising that commentators – and government officials – immediately began to offer analogies between the two to help understand both the legal basis for the raid into Venezuela and how Maduro was captured will impact his criminal case. Like how the Panama Canal itself cut that country into two, it is almost as if these two categories of analogy can be cut into valid and invalid.

Need a daily dose of reality on national and global security issues? Subscribe to The Cipher Brief’s Nightcap newsletter, delivering expert insights on today’s events – right to your inbox. Sign up for free today.

False Analogy to Operation Just Cause

Almost immediately following the news of the raid, critics – including me – began to question how the U.S. action could be credibly justified under international law?

As two of the most respected experts on use of force law – Michael Schmitt and Ryan Goodman - explained, there did not seem to be any valid legal justification for this U.S. military attack against another sovereign nation, even conceding the ends were arguably laudable.

My expectation was that the Trump administration would extend its ‘drug boat campaign’ rationale to justify its projection of military force into Venezuela proper; that self-defense justified U.S. military action to apprehend the leader of an alleged drug cartel that the Secretary of State had designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization. While I shared the view of almost all experts who have condemned this theory of legality, it seemed to be the only plausible rationale the government might offer.

It appears I may have been wrong. While no official legal opinion is yet available, statements by the Secretary of State and other officials seem to point to a different rationale: that this was not an armed attack but was instead a law enforcement apprehension operation.

And, as could be expected, Operation Just Cause – the military assault on Panama that led to General Noriega’s apprehension – is cited as precedent in support of this assertion. This effort to justify the raid is, in my view, even more implausible than even the drug boat self-defense theory.

At its core, it conflates a law enforcement objective with a law enforcement operation. Yes, it does appear that the objective of the raid was to apprehend an indicted fugitive. But the objective – or motive – for an operation does not dictate its legal characterization.

In this case, a military attack was launched to achieve that objective. Indeed, when General Caine took the podium in Mara Lago to brief the world on the operation, he emphasized how U.S. ‘targeting’ complied with principles of the law of armed conflict. Targeting, diversionary attacks, and engagement of enemy personnel leading to substantial casualties are not aspects of a law enforcement operation even if there is a law enforcement objective.

Nor does the example of Panama support this effort at slight of hand. The United States never pretended that the invasion of Panama was anything other than an armed conflict. Nor was apprehension of General Noriega an asserted legal justification for the invasion. Instead, as noted in this Government Accounting Office report,

The Department of State provided essentially three legal bases for the US. military action in Panama: the United States had exercised its legitimate right of self-defense as defined in the UN and CM charters, the United States had the right to protect and defend the Panama Canal under the Panama Canal Treaty, and U.S. actions were taken with the consent of the legitimate government of Panama

The more complicated issue in Panama was the nature of the armed conflict, with the U.S. asserting that it was ‘non-international’ due to the invitation from Guillermo Endara who the U.S. arranged to be sworn in as President on a U.S. base in Panama immediately prior to the attack. But while apprehending Noriega was almost certainly an operational objective for Just Cause, that in no way influenced the legal characterization of the operation.

International law

The assertion that a law enforcement objective provided the international legal justification for the invasion is, as noted above, contradicted by post-invasion analysis. It is also contradicted by the fact that the United States had ample opportunity to conduct a military operation to capture General Noriega during the nearly two years between the unsealing of his indictment and the invasion. This included the opportunity to provide modest military support to two coup attempts that would have certainly sealed Noriega’s fate.

With approximately 15,000 U.S. forces stationed within a few miles of his Commandancia, and his other office located on Fort Amador – a base shared with U.S. forces – had arrest been the primary U.S. objective it would have almost certainly happened much sooner and without a full scale invasion.

That invasion was justified to protect the approximate 30,000 U.S. nationals living in Panama. The interpretation of the international legal justification of self-defense to protect nationals from imminent deadly threats was consistent with longstanding U.S. practice.

Normally this would be effectuated by conducting a non-combatant evacuation operation. But evacuating such a substantial population of U.S. nationals was never a feasible option and assembling so many people in evacuation points – assuming they could get there safely – would have just facilitated PDF violence against them.

No analogous justification supported the raid into Venezuela. Criminal drug traffickers deserve no sympathy, and the harmful impact of illegal narcotics should not be diminished.

But President Bush confronted incidents of violence against U.S. nationals that appeared to be escalating rapidly and deviated from the norm of relatively non-violent harassment that had been ongoing for almost two years (I was one of the victims of that harassment, spending a long boring day in a Panamanian jail cell for the offense of wearing my uniform on my drive from Panama City to work).

With PDF infantry barracks literally a golf fairway across from U.S. family housing, it was reasonable to conclude the PDF needed to be neutered. Yet even this asserted legal basis for the invasion was widely condemned as invalid.

Noriega was ultimately apprehended and brought to justice. But that objective was never asserted as the principal legal basis for the invasion. Nor did it need to be. Operation Just Cause was, in my opinion (which concededly is influenced from my experience living in Panama for 3.5 years leading up to the invasion) a valid exercise of the inherent right of self-defense (also bolstered by the Canal Treaty right to defend the function of the Canal).

Nor was the peripheral law enforcement objective conflated with the nature of the operation. Operation Just Cause, like the raid into Venezuela, was an armed conflict. And, like the capture of Maduro, that leads to a valid aspect of analogy: Maduro’s status.

Like Noriega, at his initial appearance in federal court Maduro asserted his is a prisoner of war. And for good reason: the U.S. raid was an international armed conflict bringing into force the Third Geneva Convention, and Maduro by Venezuelan law was the military commander of their armed forces.

The U.S. government’s position on this assertion has not been fully revealed (or perhaps even formulated). But the persistent emphasis that the raid was a law enforcement operation that was merely facilitated by military action seems to be pointing towards a rejection. As in the case of General Noriega, this is both invalid and unnecessary: what matters is not what the government calls the operation, but the objective facts related to the raid.

Are you Subscribed to The Cipher Brief’s Digital Channel on YouTube? If not, you're missing out on insights so good they should require a security clearance.

Existence of an armed conflict

Almost immediately following news of the raid, the Trump administration asserted it was not a military operation, but instead a law enforcement operation supported by military action. This was the central premise of the statement made at the Security Council by Mike Waltz, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. Notably, Ambassador Waltz stated that, “As Secretary Rubio has said, there is no war against Venezuela or its people. We are not occupying a country. This was a law enforcement operation in furtherance of lawful indictments that have existed for decades.”

This characterization appears to be intended to disavow any assertion the operation qualified as an armed conflict within the meaning of common Article 2 of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949. That article indicates that the Conventions (and by extension the law of armed conflict generally) comes into force whenever there is an armed conflict between High Contracting Parties – which today means between any two sovereign states as these treaties have been universally adopted. It is beyond dispute that this article was intended to ensure application of the law of armed conflict would be dictated by the de facto existence of armed conflict, and not limited to de jure situations of war.

This pragmatic fact-based trigger for the law’s applicability was perhaps the most significant development of the law when the Conventions were revised between 1947 and 1949. It was intended to prevent states from disavowing applicability of the law through rhetorical ‘law-avoidance’ characterizations of such armed conflicts. While originally only impacting applicability of the four Conventions, this ‘law trigger’ evolved into a bedrock principle of international law: the law of armed conflict applies to any international armed conflict, meaning any dispute between states resulting in hostilities between armed forces, irrespective of how a state characterizes the situation.

By any objective assessment, the hostilities that occurred between U.S. and Venezuelan armed forces earlier this week qualified as an international armed conflict. Unfortunately, the U.S. position appears to be conflating a law enforcement objective with the assessment of armed conflict. And, ironically, this conflation appears to be premised on a prior armed conflict that doesn’t support the law enforcement operation assertion, but actually contradicts it: Operation Just Cause.

Judge Advocates have been taught for decades that the existence of an armed conflict is based on an objective assessment of facts; that the term was deliberately adopted to ensure the de facto situation dictated applicability of the law of armed conflict and to prevent what might best be understood as ‘creative obligation avoidance’ by using characterizations that are inconsistent with objective facts.

And when those objective facts indicate hostilities between the armed forces of two states, the armed conflict in international in nature, no matter how brief the engagement. This is all summarized in paragraph 3.4.2 of The Department of Defense Law of War Manual, which provides:

Act-Based Test for Applying Jus in Bello Rules. Jus in bello rules apply when parties are actually conducting hostilities, even if the war is not declared or if the state of war is not recognized by them. The de facto existence of an armed conflict is sufficient to trigger obligations for the conduct of hostilities. The United States has interpreted “armed conflict” in Common Article 2 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions to include “any situation in which there is hostile action between the armed forces of two parties, regardless of the duration, intensity or scope of the fighting.”

No matter what the objective of the Venezuelan raid may have been, there undeniable indication that the situation involved, “hostile action between” U.S. and Venezuelan armed forces.

This was an international armed conflict within the meaning of Common Article 2 of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 – the definitive test for assessing when the law of armed conflict comes into force. To paraphrase Judge Hoeveler, ‘[H]owever the government wishes to label it, what occurred in [Venezuela] was clearly an "armed conflict" within the meaning of Article 2. Armed troops intervened in a conflict between two parties to the treaty.’ Labels are not controlling, facts are. We can say the sun is the moon, but it doesn’t make it so.

Prisoner of war status

So, like General Noriega, Maduro seems to have a valid claim to prisoner of war status (Venezuelan law designated him as the military commander of their armed forces authorizing him to wear the rank of a five-star general). And like the court that presided over Noriega’s case, the court presiding over Maduro’s case qualifies as a ‘competent tribunal’ within the meaning of Article 5 of the Third Convention to make that determination.

But will it really matter? The answer will be the same as it was for Noriega: not that much. Most notably, it will have no impact on the two most significant issues related to his apprehension: first, whether he is entitled to immediate repatriation because hostilities between the U.S. and Venezuela have apparently ended, and 2. Whether he is immune from prosecution for his pre-conflict alleged criminal misconduct.

Article 118 of the Third Convention indicates that, “Prisoners of war shall be released and repatriated without delay after the cessation of active hostilities.” However, this repatriation obligation is qualified. Article 85 specifically acknowledges that, “[P]risoners of war prosecuted under the laws of the Detaining Power for acts committed prior to capture . . .”

Article 119 provides, “Prisoners of war against whom criminal proceedings for an indictable offence are pending may be detained until the end of such proceedings, and, if necessary, until the completion of the punishment. The same shall apply to prisoners of war already convicted for an indictable offence.”

This means that like General Noriega, extending prisoner of war status to Maduro will in no way impede the authority of the United States to prosecute him for his pre-conflict indicted offenses. Nor would it invalidate the jurisdiction of a federal civilian court, as Article 84 also provides that,

A prisoner of war shall be tried only by a military court, unless the existing laws of the Detaining Power expressly permit the civil courts to try a member of the armed forces of the Detaining Power in respect of the particular offence alleged to have been committed by the prisoner of war.” As in General Noriega’s case, because U.S. service-members would be subject to federal civilian jurisdiction for the same offenses, Maduro is also subject to that jurisdiction.

This would obviously be different if he were charged with offenses arising out of the brief hostilities the night of the raid, in which case his status would justify a claim of combatant immunity, a customary international law concept that protects privileged belligerents from being subjected to criminal prosecution by a detaining power for lawful conduct related to the armed conflict (and implicitly implemented by Article 87 of the Third Convention). But there is no such relationship between the indicted offenses and the hostilities that resulted in Maduro’s capture.

Prisoner of war status will require extending certain rights and privileges to Maduro during his trial and, assuming his is convicted, during his incarceration. Notice to a Protecting Power, ensuring certain procedural rights, access to the International Committee of the Red Cross during incarceration, access to care packages, access to communications, and perhaps most notably segregation from the general inmate population.

Perhaps he will end up in the same facility where the government incarcerated Noriega, something I saw first-hand when I visited him in 2004. A separate building in the federal prison outside Miami was converted as his private prison; his uniform – from an Army no longer in existence – hung on the wall; the logbook showed family and ICRC visits.

Concluding thoughts

The government should learn a lesson from Noriega’s experience: concede the existence of an international armed conflict resulted in Maduro’s capture and no resist a claim of prisoner of war status. There is little reason to resist this seemingly obvious consequence of the operation.

Persisting in the assertion that the conflation of a law enforcement objective with a law enforcement operation as a way of denying the obvious – that this was an international armed conflict – jeopardizes U.S. personnel who in the future might face the unfortunate reality of being captured in a raid like this.

Indeed, it is not hard to imagine how aggressively the U.S. would be insisting on prisoner of war status had any of the intrepid forces who executed this mission been captured by Venezuela.

There is just no credible reason why aversion to acknowledging this reality should increase the risk that some unfortunate day in the future it is one of our own who is subjected to a ‘perp walk’ as a criminal by a detaining power that is emboldened to deny the protection of the Third Convention.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief, because national security is everyone’s business.