SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW — A provision of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act that has generated controversy around fears of the potential for abuse has proven to be crucial for America’s intelligence community in uncovering a web of fraudulent North Korean activity, which had been generating revenue for its nuclear program, according to a top State Department official.

"[Section] 702 has been vital to countering these and other national security threats," said Assistant Secretary of State for Intelligence and Research Brett M. Holmgren at a Center for Strategic and International Studies event on Tuesday. “Having said all that, we appreciate the power and potential for abuse of 702 authorities without proper safeguards and controls.”

As the Biden administration ramps up efforts to win Congressional reauthorization for a provision that allows warrantless surveillance of foreigners abroad – including when those individuals communicate with Americans – a familiar debate is again heating up that pits questions of privacy against national security.

TIMELINE

- 1978 – Congress passes the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), setting procedures for surveillance and collection of foreign intelligence information

- 2008 – Section 702 is enacted as part of the FISA Amendments Act, permitting the intelligence community to surveil non-U.S. persons overseas for the purpose of collecting foreign intelligence.

- 2012, 2018 – Congress twice renews Section 702

- 2013 – Leaks from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden spawn a broader debate about the extent of the program

- 2023 – A U.S. court reveals that the FBI inappropriately sought information in a database created under Section 702, including searches on Americans suspected of criminality.

- 2023 – Section 702 is scheduled to be sunset in December, pending Congressional reauthorization

The Cipher Brief sat down with Glenn Gerstell, former General Counsel at the National Security Agency to discuss both the provision's history and its modern stakes. First enacted in 2008, as a part of the FISA Amendments Act, which amended the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, Section 702 has turned out to be an "incredibly valuable tool," said Gerstell. Without reauthorization from Congress, it is set to expire in December. That process, however, was complicated earlier this month after a U.S. court revealed that the FBI conducted improper widespread searches under 702, including on Americans suspected of crimes. Those findings were explained in a court order issued last year by the U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which oversees such efforts. "The FBI wasn’t undertaking these searches maliciously, but because they thought they were pursuing their legitimate government goals," noted Gerstell. "But there were clear misunderstandings and errors. The FBI, after criticism from both privacy advocates as well as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, changed its procedures in late 2021, and greatly restricted its ability to do these queries."

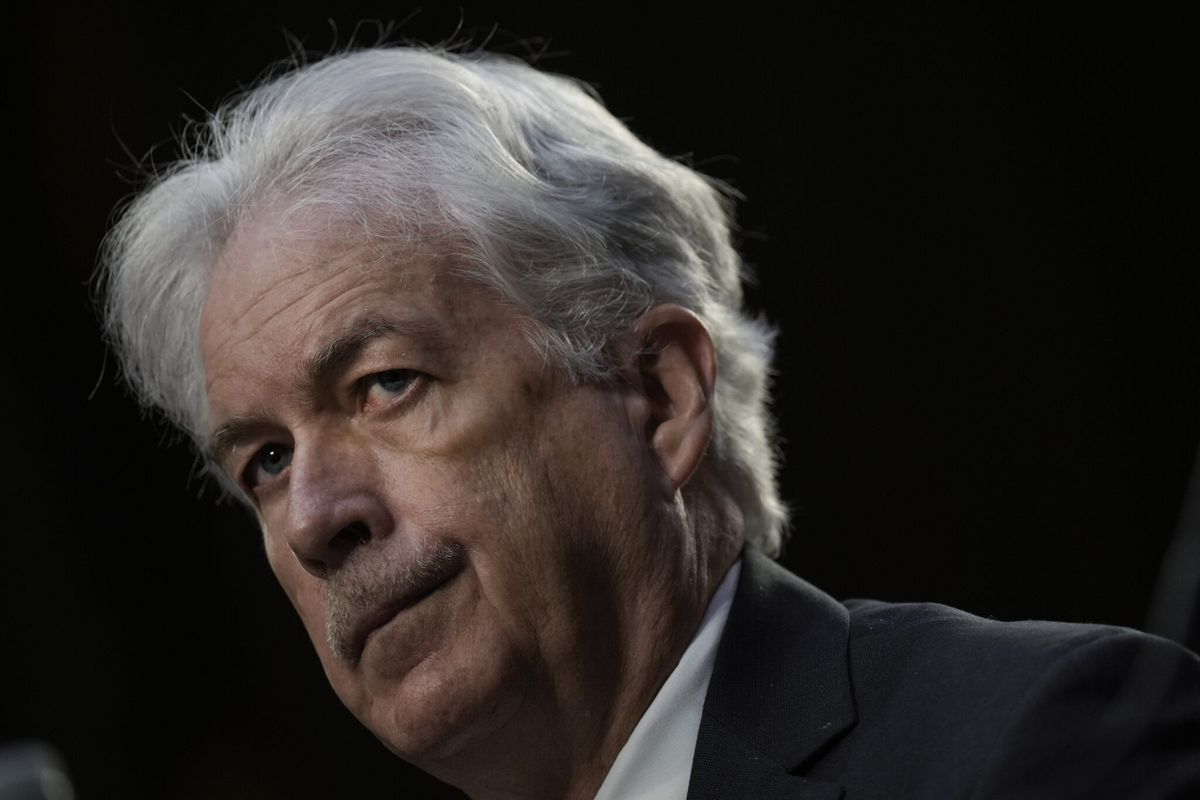

Glenn Gerstell, Former General Counsel, National Security Agency

Glenn Gerstell, a Senior Adviser at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, served as the General Counsel of the National Security Agency and Central Security Service from 2015 to 2020. Prior to joining NSA, Mr. Gerstell practiced law for almost 40 years at the international law firm of Milbank, LLP, where he focused on the global telecommunications industry and served as the managing partner of the firm’s Washington, D.C., Singapore, and Hong Kong offices.

The Cipher Brief: What have been some of the key successes and failures associated with Section 702?

Gerstell: We have to go back to 1978, when the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act was established, which was designed to codify the ability of the intelligence community to do electronic surveillance and also physical surveillance for foreign intelligence purposes. To some extent, that grew out of the recognition that the law in that area wasn’t really well-developed. There had been abuses by elements of the intelligence community and law enforcement during the Nixon years, which were highlighted in the Church-Pike hearings in the 70s.

There was a recognition that the law in this area needed to be codified for foreign intelligence purposes, as well as to provide a means to compel electronic service providers, because they needed a search warrant or some legal process to compel them. I’m greatly simplifying it, but thus was born the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, which defined electronic surveillance in a very specific way — in particular, in those days, most international phone calls were carried via satellite and interception of radio transmissions and satellite transmissions was fundamentally excluded from the operation of that statute.

As things changed due to technological changes, in the early 2000s, more and more communications, instead of being transmitted through satellite, were being transmitted through submarine cables, terrestrial lines, other systems, which meant that it was an unusual outcome. Which is that in order to intercept a foreign transmission, the intelligence community was finding it necessary to get a court order under FISA to do surveillance on foreigners, which ended up meaning that foreigners were getting additional protections under the Fourth Amendment that they weren’t entitled to, because the Fourth Amendment doesn’t apply to foreigners located outside the United States.

This was an unintended result due to a change in technology, which meant that the United States government was needing to get probable cause court orders from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court in order to do certain kinds of surveillance. So that was recognized as being unsustainable and inappropriate and that provided the impetus for Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which set up an entirely new scheme. It basically recognized that in order to do foreign intelligence surveillance on foreigners located outside the United States, who were not entitled to the protections of the Fourth Amendment, a lower threshold needed to apply.

Under Section 702, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court approved procedures for intercepting, for targeting, for minimizing the communications of Americans and for disseminating information, and the broad types of surveillance under what’s called certifications were approved by the court, but not the individual specific targets.

That made it easier and in compliance with the Fourth Amendment, the United States government could target foreigners living overseas, who were believed to possess foreign intelligence information. In order to target a foreigner overseas, no particular court order or probable cause was needed. Indeed, it would be rare for the government to have probable cause to target someone if all they’re acting on is a tip.

That’s the essence of 702, aimed at non-US citizens who do not enjoy Fourth Amendment protection. They must be located outside the United States. They must be reasonably believed to possess foreign intelligence information. The government can then target them and go to a US communications service provider and say, in effect, with that directive, “Please give us the communications information of this foreign target.”

No US citizen anywhere around the world can be a 702 target ever, period, under any circumstances.

Looking for a way to get ahead of the week in cyber and tech? Sign up for the Cyber Initiatives Group Sunday newsletter to quickly get up to speed on the biggest cyber and tech headlines and be ready for the week ahead. Sign up today.

The Cipher Brief: You mentioned technological shifts that took place from the 1970s to the more modern era. At the same time, there were also sizeable geopolitical shifts. How has that impacted the use of - or the need for - 702?

Gerstell: It became very clear obviously after 9/11 that our national wellbeing wasn’t merely a function of the capabilities of adversaries’ weapon systems, namely worrying about Russian nuclear submarines and Russian bombers, but indeed we could well be affected here in the homeland by international terrorism, and also increasingly by cyber maliciousness that doesn’t know sovereign boundaries.

In other words, our homeland security was threatened not by things happening across an ocean, but possibly by activities that would manifest themselves or make themselves present here on the homeland soil. So, that greatly increased our intelligence needs to find out about this kind of threat.

The Cipher Brief: Can you talk more about 702 in the context of those mounting cyber threats?

Gerstell: It’s pretty clear we face some significant levels of cyber threat, although they haven’t yet manifested themselves on American soil in a really strategic outcome-changing way, but nonetheless we’re all aware of them. Because we see what Russia and North Korea and Iran and China are capable of in this area. We’ve seen the devastating effects of ransomware throughout the United States in virtually every industry.

There’s no question we need to be better informed about foreign cyber adversaries. In particular, the activities of four countries, North Korea, Iran, China, and Russia. It so happens that 702 is a perfect tool to enable us to learn about adversaries’ intentions, plans, their tactics, their procedures, because by definition, those foreign cyber actors are targeting American electronic infrastructure. That’s exactly what Section 702 is about. It’s about lawfully leveraging American communications providers to gain insight into foreign activity, whether that’s foreign cyber maliciousness or other acts of people located overseas.

It turns out that 702, although that wasn’t the intent back in 2008, has turned out to be an incredibly valuable tool in discovering and disrupting malicious cyber activities. In theory, that’s potentially everything from tracking down cryptocurrencies that ransomware gangs are using, to understanding the activities of entities like the PRC Ministry of State Security that has a long record of cyber maliciousness, to entities like the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg that was involved in the 2016 election interference.

The Cipher Brief: Some of the pushback, particularly from civil liberties advocates, is that the FBI has access to data that’s swept up by 702. In an October 2018 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court opinion, Judge James E. Boasberg wrote that there still appears to be widespread violations of the querying standard by the FBI, and questions about the agency’s capacity or adherence to even basic privacy practices. Can you talk about what has happened since then to address those concerns?

Gerstell: Since 2008, when Section 702 was adopted, it has been controversial. It was not passed unanimously. In fact, every time it’s been renewed, it’s been renewed with declining margins of the majority. It is controversial, mostly because of what’s called incidental collection of communications of Americans.

There’s a separate additional concern, more on the part of people located in Europe and Asia, that the United States is using Section 702 in improper ways from their viewpoint to do surveillance. The foreign concern has not historically been a big factor in the United States reauthorization debates because I think most people recognize that the United States is entitled, as is every country, to do some level of surveillance for its national security purposes.

The Biden administration does want to try to accommodate the Europeans in some of these areas where they have expressed concerns about surveillance. But the focus of attention here has been what’s called incidental collection of Americans’ communications with 702 foreign targets.

Most foreign targets under 702 are not talking to Americans. For example, if hypothetically the US was targeting a minister in a government located overseas because we want to learn more about that government, then he or she is probably talking to people in their country rather than Americans. On the other hand, there clearly are some targets who would be expected to be talking to Americans — hypothetically the intelligence community could be targeting a foreign country’s spy who was known to be recruiting Americans, for example. Those communications could be scooped up inadvertently, because the Americans aren’t the target. This issue of the extent of incidental collection – and how it can be accessed — is probably the primary concern in the current debate.

Most of the concern over incidental collection has been about the FBI, not about NSA or CIA or the NCTC, the other three entities that get so-called raw communications, meaning the communications that are directly from the service providers. That’s because the FBI has two missions. It has both a foreign intelligence mission in the counterintelligence area and it also has a domestic law enforcement mission. That’s indeed it’s bigger mission. Because of that, the FBI over the years has generated controversy over its ability to acquire that information, look at that information, store it and analyze it in pursuit of its two missions.

There have been years of differences of opinion between the FBI and the Department of Justice and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court over exactly the extent to which the FBI, in pursuit of those two missions, is able to look at the database of information that it is acquired under Section 702. It’s given rise to Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court opinions that said, “You’re not doing this properly.” I might add, the FBI wasn’t undertaking these searches maliciously, but because they thought they were pursuing their legitimate government goals, but there were clear misunderstandings and errors.

The FBI, after criticism and from both privacy advocates as well as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, changed its procedures in late 2021, and greatly restricted its ability to do these queries.

There’s a lot of misunderstanding about this. The Annual Statistical Transparency Report for 2022 says that there were roughly 245,000 foreign targets under 702. Of those, a little over 3%, about 7,800 foreign targets, were ones that were pertinent to what’s called a fully predicated national security investigation by the FBI. Only those 7,900 are the ones whose communications were sent to the FBI. So the first thing to realize is that it's a small subset of any given year’s 702 collection.

Some of those 7,900 foreign targets were in communication with Americans and those communications are included in the FBI’s database. The issue arises, under what circumstances can the United States use a what’s called a US person query term — for example, an American name, a phone number, an IP address, an email address — to look through that database?

There are two circumstances which they can do so. One is they can be searching that database for foreign intelligence information. For example, if the FBI were investigating the efforts of a Chinese recruiter on US campuses, they might want to see who that person is talking to. They could be searching with an American’s name to warn them of the recruitment effort.

There’s not too much controversy over that. Generally, no search warrant is needed to undertake such a search or query – although I should add that some privacy advocates believe a court order is needed even in such cases. But the area of greater concern is where the FBI is using an American search term in that database seeking evidence of a domestic crime, not foreign intelligence information.

The reason it’s of such concern is the whole idea behind 702 was to elicit information about foreigners for foreign intelligence purposes. It wasn’t designed to get information about Americans. The privacy advocates say in essence, “Wait a minute, you’re taking a windfall so to speak, of using this information about Americans, which the FBI wouldn’t normally be entitled to get because it doesn’t have a search warrant. The FBI happened to get it only because some Americans were talking to one of the 702 targets, and now the FBI is investigating this not for 702 purposes, but for domestic crime purposes.”

That’s the essence of the privacy advocate’s concern. And to be fair, that’s a reasonable point. So in response to the criticisms, the FBI did a couple of things. Most importantly, they now require that before an agent searches the so-called 702 database, he or she must affirmatively opt into it on their computer. It doesn’t automatically default to this. They need to affirmatively select the 702 database on their computer. They need to describe the justification in their own words, not just select from a drop down menu.

They need to articulate why it is they think they have a reason to look at the 702 database in particular. The new rules are clear, that they can do so only where they have a “specific factual reason” for believing that the 702 database is likely to have evidence of the crime they are searching for. In other words, it’s not just a hunch, not just a tip, not just a wild guess, not just, “Let’s just search it to see whether anything turns up.”

In short, they need to have a specific factual basis for thinking there’s a reason that the 702 database is likely to yield a hit. The consequence of that new requirement is that as you might expect, the number of queries has plummeted by over 90% – in the prior year, they had had something like three million US person queries, and that’s dropped to below 120,000 US query terms.

I should add that this whole area is quite complex and obviously I’m just summarizing here, but I think these are the key points.

The Cipher Brief: Let's talk about the data itself. Once information is swept up, sometimes including data relating Americans, what happens to that information? How long is it kept? How long is it stored? Where is it stored, etc?

Gerstell: The data is collected through some combination of the National Security Agency and the FBI, which get the information from the electronic communications service providers. That information is stored in the government agencies’ computer systems, subject to restrictions and rules on who can access it and under what circumstances. And it’s generally retained for five years, and then it’s automatically deleted. There are exceptions, of course.

The Cipher Brief: You mentioned that there’s been declining support for 702 with each iteration of reauthorization. if you had the capacity and power to change 702 it in any way or improve upon it, what would you do?

Gerstell: Ultimately, we are going to have to recognize that the way the courts have applied the Fourth Amendment to specific cases of technology over time has resulted in a somewhat arbitrary scheme of domestic and foreign intelligence surveillance authorities. If you were designing a legal system for such surveillance starting with a blank sheet of paper and our American values, you wouldn’t come up with our complex arrangements that vary with location of the target, the means of interception and so on. I’m not suggesting any diminution of the Fourth Amendment in the slightest, just to be clear. At some point our nation will want to think this through more carefully.

By and large, Section 702 has proven to be a scalable, sustainable way of acquiring foreign intelligence information from foreigners who are using American communications infrastructure, all in a manner consistent with our values and the Constitution. We’ll have to see how the statute works with today’s threat landscape. Potentially, there are areas where it might make sense to expand the flexibility of Section 702. Right now, it’s limited to topics that are covered by court-approved certifications. It might be necessary to have a more agile, quicker system to deal with today’s dynamically changing threats.

In a way, it’s a testament to American communications infrastructure, that’s so many foreigners are using American systems. They’re using Gmail, Yahoo, Outlook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, etc. To be clear, I am not saying all or any of those are indeed 702 service providers, but I’m simply noting that the world uses American communications infrastructure, and 702 has proven to be a very good and appropriate tool for accessing foreign intelligence information.

The Cipher Brief: What expected impacts do you see if 702 is not reauthorized?

Gerstell: Put aside the technical question about the ability to continue ongoing investigations for a certain short period of time after the lapse of the statutory authority. But fundamentally, it would mean that we’ve just put blinders on the United States’ ability to protect itself from foreign threats. That just makes no sense at all.

That’s not in the Republicans’ interest, it’s not in the Democrats’ interest; it’s not in the interest of the political left, or the right. We’d be hurting ourselves and exposing ourselves to far greater vulnerability, from everything from ransomware to terrorist attacks, to all sorts of foreign advantages. This would affect our ability to assist countries like the Ukraine and Taiwan, and expose our men and women around the world in uniform to dangers that we will not have any visibility into.

There’s just no universe in which that makes any sense, given the nature of today’s threats and given how they’re communicated through electronic communications.

Having said that, it doesn’t mean the statutory scheme can’t be improved. Are there areas in which the querying procedures could be adjusted? Are there areas in which the FBI might be subject to further restrictions? That’s all subject to fair debate, and there are important discussions between Congress and the Executive Branch on all this. But the idea of just simply saying, “Oh, we don’t really need 702,” is… well, I’m struggling to find an adjective. It’s approaching suicidal in national security terms.

If we allowed 702 to lapse, we’re then left with the government’s ability under Executive Order 12333 to acquire foreign intelligence information overseas. That’s important, but not a substitute for Section 702. Many of the foreign spies, terrorists and others we’re interested in are using American communications infrastructure. We’d be blinding our eyes to a big part of national security threats if we eliminate 702."

Updated 6/2

Read more expert-driven national security news, analysis and opinion in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business