EXCLUSIVE SUBSCRIBER+ INTERVIEW — An old friend of Beijing returned to China this week in a move that harkens back to a time when Manila had a far more fraught relationship with Washington. Former Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte – known for his pro-China policies – as well as his concerns that his country could become a “graveyard” should it become entangled in U.S.-China tensions, sat down for a surprise meeting on Monday with Chinese President Xi Jinping. The move prompted current Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to express hopes that Duterte address controversial Chinese moves in the South China Sea, though he also welcomed the increased communications between the two countries.

“It's a very complex geopolitical reality, and we happen to be in a very strategic geographical location,” Philippines Ambassador to China, North Korea, and Mongolia, Jaime FlorCruz told The Cipher Brief in an exclusive interview just prior to Duterte’s visit. “We just hope that we won't be forced to choose sides between the two superpowers in our region.”

For a deeper understanding of America’s oldest ally in Southeast Asia and its relations with a rising China, The Cipher Brief conducted a wide-ranging interview with Ambassador FlorCruz, who has lived for more than 50 years in China, much of which spent — prior to his ambassadorship — as a journalist for TIME magazine and CNN.

The subsequent conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

TIMELINE OF EVENTS

- 2016: Rodrigo Duterte becomes the President of the Philippines, pledging to shift foreign policy away from the United States in favor of China and Russia.

- 2016: An international tribunal in The Hague issues a rebuke to China sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, including Beijing’s building of artificial islands, finding those claims have no legal basis – a first for the Chinese government to be summoned in front of the tribunal.

- 2016: Duterte visits China, signaling a thawing of relations between Manila and Beijing, as well as the signing of several bilateral trade agreements.

- 2017: The U.S. and the Philippines conduct joint military exercises, pointing to sustained security collaboration between Manila and Washington. A year later, they reaffirm a mutual defense treaty.

- 2018: China and the Philippines conduct joint oil and gas exploration efforts in the South China Sea

- 2020: The Philippines threatens to end the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), which allows American forces to be stationed across the country.

- 2021: Manila sends two new diplomatic protests to China over Beijing's decision to keep "threatening" vessels in contested areas of the South China Sea.

- 2022: The Philippines holds presidential elections, resulting in the election of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, which results in a shift in foreign policy to a more U.S.-friendly positioning.

- 2023: Washington and Manila announce an expanded U.S. military presence and increased U.S. access to bases across the country. The two countries hold 18-day joint military drills, involving an estimated 17,000 soldiers.

- 2023: Chinese President Xi Jinping calls on a former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte to “play an important role” in fostering ties between Manila and Beijing during a Duterte visit to China.

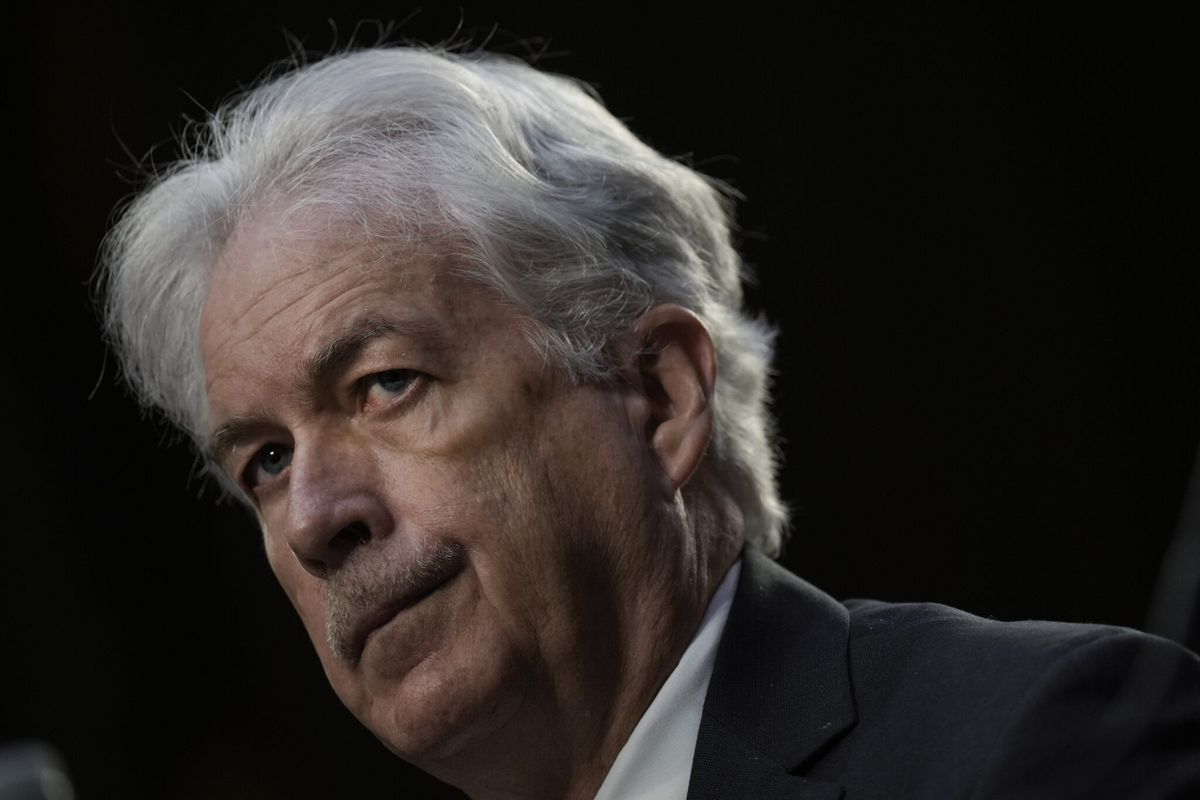

Jamie FlorCruz, Philippines Ambassador to China, North Korea, and Mongolia

Jaime A. FlorCruz is the current Philippine Ambassador to China, North Korea, and Mongolia, having held that position since December 2022. Prior to that post, he served as CNN and TIME Magazine’s Beijing Bureau Chief, and was often thought of as the dean of the foreign press corps in Beijing, being the longest-serving foreign correspondent in China. FlorCruz was also a two-term president of the 200-member Foreign Correspondents' Club of China, and Edward R. Murrow Press Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. He studied at Peking University with the famous Class of ’77, alongside classmates who would later go on to comprise much of China’s governing hierarchy, including former Chinese premier Li Keqiang. FlorCruz authored “The Class of ‘77: How My Classmates Changed China,” as an accounting of that experience.

The Cipher Brief: Let’s start with some context into the nature of your role. As Philippines Ambassador to China, North Korea, and Mongolia, you have a diplomatic tight-rope to walk, especially given renewed U.S. interests and military presence in the region. How do you manage that?

FlorCruz: We always remind ourselves that our differences with China is not the totality of our relations. We try to manage our differences by continuing to talk with them, communicating. We differ on many issues, especially territorial and sovereignty issues, but we've tried to strike a middle road in terms of our relations with China and the other superpower, the United States. We believe that we proceed from our national interest, whatever's good for our country, that's what we do. But it's a very complex geopolitical reality, and we happen to be in a very strategic geographical location.

We're like a beautiful maiden being courted by two strong suitors. And so we believe that by striking a middle road or being in between, that we could benefit from the two relationships that we have. It's easier said than done, and it entails patience, diplomacy, astute kind of diplomacy, and certainly better communications, improved communications between the two sides. We just hope that we won't be forced to choose sides between the two superpowers in our region.

My focus is really on getting the most pragmatic or tangible interests from our relations with China, and that involves pushing for better trade investments, Chinese investments to the Philippines, and also knowledge transfer. There are many things that we could get from our relations with China which align with our national priorities in the Philippines. Our president, Ferdinand Marcos Jr, came here in January during which he had top level meetings. Many MOUs [memorandum of understandings] and pledges made. $22.8 billion worth of projects and pledges. My mandate is to get those projects through and deliver them.

Our focus is on agriculture, infrastructure, connectivity, as well as people to people exchanges. And those are the four priorities that the president set about doing. I've been busy visiting Chinese companies along this line. I visited China Power Projects and saw their wind power, solar power combined with agricultural production. I also visited their plant producing batteries, storage kits that can combine into mini grids. We need them badly. Energy is one priority that we wish to bring to the Philippines.

Looking for a way to get ahead of the week in cyber and tech? Sign up for the Cyber Initiatives Group Sunday newsletter to quickly get up to speed on the biggest cyber and tech headlines and be ready for the week ahead. Sign up today.

From solar and wind to water resources and battery storage, electric vehicles, those are the kind of projects that we are interested in. And I hope that in the next few months I can convince these Chinese companies to invest in the Philippines. Even better if they could move some of their production lines to the Philippines so that we can create jobs and also sell them domestically, and maybe even export them as joint venture products. That's one focus that I've set about.

I also wish to promote more exchanges. Tourism as been a big source of revenue. Before the pandemic, we had 1.8 million arrivals from China at that time. We’re hoping to improve our visa processing and are going to pilot e-Visa, meaning electronic visas, to make it more efficient and convenient while at the same time making sure that our security and safety concerns are also covered, using modern technology and AI.

The Cipher Brief: I want to talk about the AI component. But before we do, let’s discuss that expanded defense agreement between Washington and Manila, which includes access to a number of new military bases. This, of course, comes amid growing concerns of Chinese posturing in the region. So when you're discussing American military presence across the Philippines with your Chinese counterparts, what do you say? What is their reaction, and the dynamic there?

FlorCruz: It's, of course, natural or expectable that China will have concerns about the Philippines relations with the US. What we tell them is basically whatever we do proceeds from our national interests, and that includes modernizing our national defense. And we assure them that it's not aimed at a third country or a third party. We believe that we can seek to improve our national defense by gaining from relationships with other countries. The Chinese understand that we have an old friendship and alliance with the United States. I think they have no problem with that, but they just need to be assured that whatever steps are taken in the region are not aimed at themselves, at China, or any other parties.

It's whatever is pragmatic and good for our country. But it entails explanation, it entails reassurance, and the building of trust and confidence. And that goes across the board. We tell our friends here in China that our aim is to be friends to all and enemy to none, and that's our guiding principle in terms of striking that middle road among the powers in the region.

The Cipher Brief: In that same vein, when talking about national interests and sovereignty, just this month the Philippines military reported what they called an alarming increase in the number of Chinese fishing vessels in the South China Sea, where China has made sweeping – albeit disputed — claims of sovereignty. It’s been a sore point in relations between Beijing and Manila about who exercises control in the region. How do you manage that with your counterparts in China, and what are you trying to practically accomplish?

FlorCruz: It's a matter of pushing for better communications the same way that the US has been asking for better and direct communications between the two defense establishments. What we really want is to avoid any misunderstanding, miscalculations, and unintended consequences, and I think that's shared by both sides. The aim is to exercise self-restraint and professionalism, as well as real-time communications by both sides. I think no one wants to see unintended consequences. And again, it entails patient diplomatic interaction, exchanges.

The Cipher Brief: Going back to economic ties, what are some of Manila’s goals amid this ongoing chip war between Washington and Beijing, and more generally as it seeks to forge closer trade ties across the region?

FlorCruz: Our needs are more basic than that, agricultural production, for example. China in some aspects have made big inroads, [particularly] with battery technology and robotics. They have managed to bring down the cost of making these batteries. And the best part about it is you can put together these batteries, big batteries, and form a mini grid, which suits our archipelagic geographical features. We have so many islands and it's very difficult for us to connect these sources of energy into grids. Places now have wind power and solar power. They need to find a way to store this energy. And these storage systems that the Chinese have improved, if not perfected, will suit our needs.

I've been trying to convince companies to invest in the Philippines for their factories. We can mutually benefit from such investment. We need them. Energy is very high priority in the Philippines. As you know, without energy, there are many things you cannot do if you don't have a constant energy source. We also need more infrastructure projects, bridges, railways. And China has this BRI, Belt and Road Initiative. It happens to be the 10th year anniversary this year of BRI. And the BRI project intersects quite well with our infrastructure project or program.

The Cipher Brief hosts expert-level briefings on national security issues for Subscriber+Members that help provide context around today’s national security issues and what they mean for business. Upgrade your status to Subscriber+ today.

If you've been to the Philippines, you'll see a lot business opportunities in terms of upgrading our infrastructure. That's where I think the Chinese investment and technology comes in. China has made leaps and bounds in terms of roads, bridges, railway, and high speed railway. We don't even need high speed railway in the Philippines. If you could only have a railway system that would ply long distance at 120 kilometers per hour, we would be happy. The Chinese now are in the 350 kilometer per hour speed. China has much to offer in terms of upgraded technology.

I also want to tap into the Chinese education. We want to bring more students here, not just to learn the language, but also to learn some of the engineering and science aspects that the Chinese have become very proficient at. And I hope these students could find internships and maybe jobs in the future along those lines. Yes, we are building a railway link now from Manila to Clark, northwards, and I think it'll be finished in two years or so. Well, we need a lot of railway engineers, for example. We haven't thought about that. And so I think those are the kind of pragmatic projects that I hope to push in the coming months and years.

The Cipher Brief: We've seen a lot of recent activity between the United States and China, both in terms of tit-for-tat sanctions, tit-for-tat war games, but also in diplomatic endeavors, for instance, from those like US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, and US Envoy John Kerry in their recent visits to China. In watching this from your ambassador’s perch, I’m wondering if you see any opportunities to take down the temperature between these two nations.

FlorCruz: The visit by Yellen seems to have lowered the temperature and maybe increased mutual accommodation. It kind of reminds me of China and the US in the '70s. And so I've asked this question: How was it that the two countries were even more different than they are now, still managed to coexist, particularly after Kissinger came, and then Richard Nixon came in 1972. I look back and I see how different the two countries were at that time, ideology, culture, mutual distrust, suspicion after so many years of no communication, no interaction, and yet they somehow managed to shake hands and reach rapprochement, and co-exist. Perhaps it was because they had a mutual enemy in the former Soviet Union was one of the common interests that brought the two together.

Now you have China rising as a global power. And so some people described this as the Thucydides trap trap, when you have the status quo power being threatened, feeling threatened by a rising power and that they're bound to clash or go to war. Hopefully not. There are elements on both countries who would rather not see a war breaking out between the two big powers now. And for us caught in between, we too hope that the two big powers could sort out their differences and come up with a modus vivendi. I think we need, of course, statesmen on both sides to look at the bigger picture and sort things out.

Of course, we cannot ignore the differences between the two powers from national security, to freedom of navigation, to even cyber and space confrontations. But we hope that the two big powers can coexist and find where their national interests intersect, coincide, and then settle their differences through negotiations, through dialogue, but with pragmatic result-driven goals. We believe that the globe is big enough for the two superpowers to coexist, and for us as well.

The Cipher Brief: You have a true insider’s perspective on China, particularly its hierarchy, having attended Peking University as a student with classmates who would later become among China’s ruling class, including former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang. What sort of insights can you provide having had that experience?

FlorCruz: I was very fortunate to have studied at Peking University during the time when this class of '77 entered the university. For nine years, there was no such kind of college national entrance exam. That year, 1977, was the first time they restored it, they resumed it. Some 5.7 million youth took that exam, and only about 400,000 got in because there were very few slots yet at that time. But that made them very special, not just because of the number of people involved, the cream of the crop, so to speak. It turns out that most of them had already spent years working on the farm or in the factories or serving in the army. So they possessed rich social experience already. And even more, they knew the Mao period, and they were passionate about changing things around. They were passionate for reform.

Initially, I don't think many of ours knew what reform meant or what it entailed, but the best part about being in school at that time was to be infected with that sense of mission to change China. And in a way I was part of that of that evolution. Deng Xiaoping called it The Second Revolution. I did not just witness it, I experienced it. I was part of that change, and that's what I tried to impart or capture in writing my book, the sense of excitement, but the sense of passion, but also the sense of suspense, because we really didn't know what China was going to be pursuing that path of reform and opening up.

I myself had doubts about how far China should go in terms of changing, in terms of opening up. But my classmates, they knew that China had to change and that they were going to be part of that change. And that's why they were so dedicated, they worked so hard. I remember going to the library, and it's very hard to find a seat. So students would either miss or do their lunch while in the library because they didn't want to give up their seats, that was how passionate they were. I remember whenever there was a new magazine, or sometimes I would get foreign books or foreign magazines. And they would all be coveting whatever I had. They were very curious, exploring new ideas. That was how exciting it was learning with them. And then they turned out to be part of Deng Xiaoping's shock troopers of reform.

The Cipher Brief: You often mention “what China will be.” That's still an open question in some ways, given the nature of technological advancements, industrialization, and economic reforms. And yet some of those facets, particularly the economy, are now showing signs of plateauing. Given that, from your perspective, where is China heading, and how might that knowledge play into new opportunities in managing that relationship?

FlorCruz: When Deng Xiaoping embarked on that reform and China’s opening up, I don't think they had a well charted course. In fact, there was a popular analogy which says that China was trying to feel the stones under the water while crossing the river. There was a lot of experimentation, a lot of risk taking because crossing that river, they couldn't really see the treacherous stones underneath their feet. That was, in a way, the most apt description of the past 30 years of reform. A lot of it was piloting certain concepts, economic zones, were set up precisely as laboratories to pilot concepts, new ideas, new ways of doing things. And what they did was whatever worked, they replicated, whatever did not work, they moved on and tried another concept. And that's Deng Xiaoping's approach.

Of course, over 30-plus years, which in Chinese history is just a wink of an eye, I witnessed remarkable changes, lifting 300 million out of extreme poverty. That was something impressive. But also in terms of even just the physical look of many cities, I could not have imagined 30, 40 years ago. But yes, there are many problems that are confronting China now. Some of these problems were the result of the changes. In other words, changes begot new problems.

The one child policy that was meant to solve overpopulation now has become a problem. You have an aging population and a shrinking population. Double-digit economic growth led to pollution, economic degradation, water, air, soil. They have a big problem in environmental degradation. Yes, I believe that as China moved on, they're now facing a new set of problems. Corruption is there, in spite of the sustained campaigns against corruption. There's the gap between the rich and the poor, they have many millionaires, multimillionaires, but in spite of the success in lifting millions of people out of extreme poverty, there are still pockets of poverty, pockets of backwardness, especially in the western part. They have a gap between the rich and the poor, gap between the eastern seaboard and the western mountainous areas.

You also have the spiritual crisis that China has been facing all this time. The changes of the past 40 years have meant that the younger generation, especially, are no longer in sync or locked in step in terms of ideology. Many of them grew up not under the red flag, as the Chinese put it, but many of them grew up influenced by foreign concepts, and Hollywood, and NBA, and the internet. So I think China is no longer the monolith in terms of most people thinking the same way. And that has become even more difficult with the social media and the internet. Yes, the government still controls the narrative. They still tightly control the mainstream media, but there's still a strong influence of social media, and so China has been more porous than before.

The Cipher Brief: Let’s briefly transition to North Korea, where you are also Manila's ambassador to Pyongyang. What do you hope to accomplish there, given the increase in missile launches, a US sub docking in South Korea, and a general uptick in tensions in the region?

FlorCruz: I hope that somehow we could help restart talks or exchanges. North Korea is like China 40, 45 years ago, isolated, and yet there's a lot of potential. A few years ago there's been a series of talks involving the US and Six Party Talks. I hope that somehow that such talks could be resumed. Of course, that's probably way down the road. But in the meantime, I just hope that we could update our knowledge of what's going on in North Korea.

Again, it strikes me that North Korea is just like China 45 years ago. We hardly know what's going on there. It's a very important place, it's people are hospitable and hard working, and I think they can benefit from opening up more engagement with the so-called outside world. China is one of the few entry points to North Korea. I know probably it sounds ambitious, but I'm looking forward to just visiting so we can start engagements and exchanges.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspectives and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business