The revised ban on travel and immigration from six Muslim-majority countries ordered by President Donald Trump on March 6 now sits before the Supreme Court, waiting for a final decision on its legality. However, the court’s decision in June to reinstate the executive order until a decision is made – except in cases where the individual has “a credible or bona fide relationship” with a U.S. person or entity – has led to a rolling implementation of some of the order’s restrictions.

The cable circulated by the State Department to U.S. consulates on July 12 revealed how some of these restrictions may begin to affect visa applicants. The new State Department guidelines – set to be implemented within 50 days – form part of the so-called “extreme vetting” procedures that the Trump Administration has promised to secure the U.S. against terrorist infiltrators. From biometric passports to new biographical information requirements for applicants from certain countries, these guidelines join a number of other measures, which are gradually restricting travel and immigration into the United States.

The question now is, will these and other restrictions protect Americans from terrorist acts, and what sort of backlash will these extra security measures elicit from the countries targeted?

For the most part, the guidelines are simply clarifying new methods and processes that will allow U.S. intelligence and counterterrorism agencies to better ascertain the identities of foreign visitors and add valuable data points to their analysis of terrorist organizations. Some of the new standards will be difficult for targeted countries to meet, but the policy does allow for a delay in full implementation of the guidelines if a foreign government is making good faith efforts to update its recordkeeping and identification systems.

According to former Acting Assistant Secretary for Homeland Security and Cipher Brief Network member Todd Rosenblum, the new State Department guidelines are “largely legitimate.” He says that the security measures requested in the guidance are “reasonable and well thought out,” and that the document “has the feel of a planned, debated and consensus effort that involved the entire U.S. interagency, from FBI to State, DHS, the Intelligence Community, Commerce, HHS and DoD.”

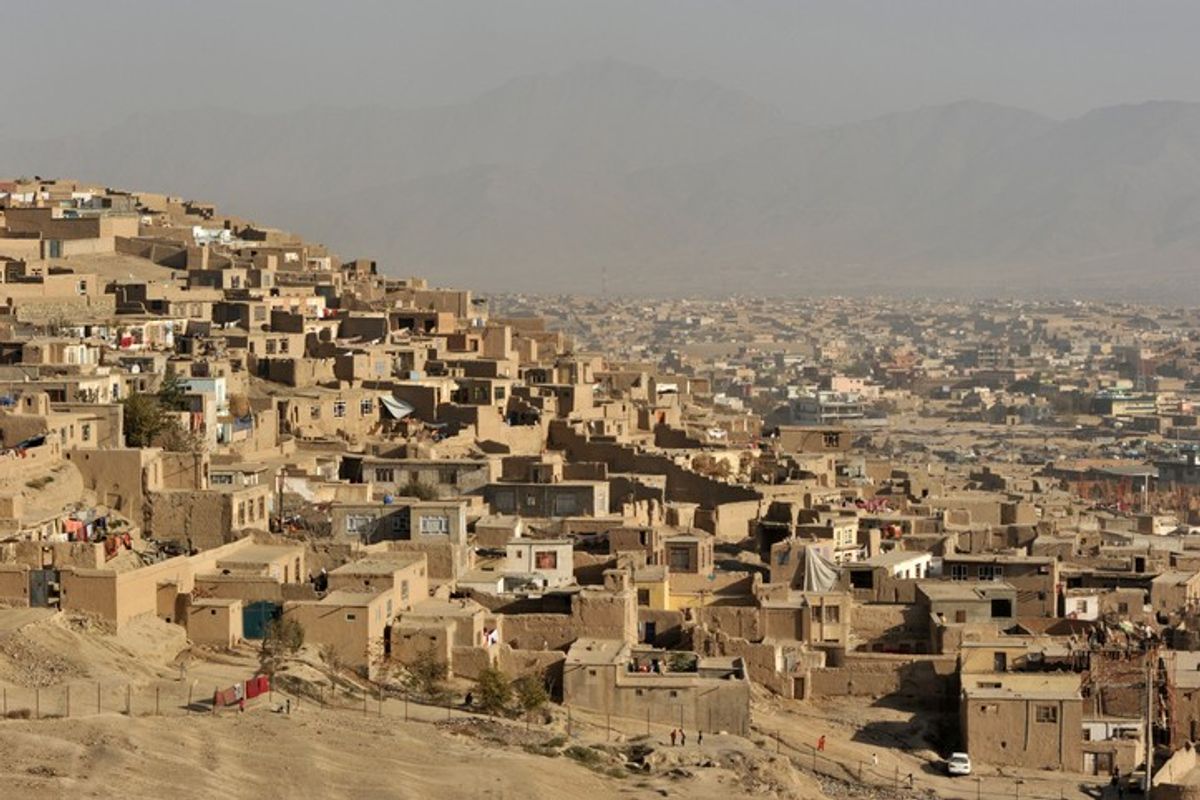

However, taken in the context of the travel ban and other “extreme vetting” measures, the guidelines do appear to fit a pattern of increased U.S. immigration and security measures specifically targeted at Muslim populations. For instance, an Office of Management and Budget emergency review published in May has pushed through new requirements for visa applicants from “populations warranting increased scrutiny” – which many read as code for Muslim populations – to submit more personal data going back years, and provide detailed information from social media accounts. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s decision to partially reinstate the travel ban has thrown the status of thousands of travelers and visa applicants into confusion over the definition of what exactly constitutes “a bona fide relationship with a U.S. person or entity.” In response to negative press, the State Department has now relaxed its definition of what constitutes a close family member to include grandparents, and the White House overrode two visa rejections to allow an all-female Afghan robotics team to compete at a DC-based competition last week, but many more less-celebrated cases remain in limbo.

This is a problem for two reasons. First, says former Associate Deputy Director for Operations at the CIA and Cipher Brief expert Robert Richer, most foreign governments will work with the U.S. to implement new security measures but “you do reach a threshold…where reciprocal actions start to take place.” At that point, the travel ban and associated restrictions may begin to noticeably degrade U.S. relations with certain countries and result in retaliatory limitations on Americans traveling to those countries.

At the same time, the effect of what is increasingly seen as a ban against Muslim travel to the U.S. could have a chilling effect on U.S. public diplomacy and reduce grassroots economic ties between the U.S. and countries targeted by the new restrictions. There are signs that this is already beginning to happen. Visa requests granted to almost 50 Muslim-majority countries have declined by roughly 20 percent since Trump took office, and according to tracking data from Foursquare – a company that tracks international foot traffic through its app on millions of smartphones – total visits to the U.S. have decreased by as much as 16 percent since President Trump took office.

The second issue is one of efficacy. President Trump and his surrogates have insisted since the campaign that the travel ban and other new security measures are necessary in order to secure the United States from terrorist operatives or sympathizers attempting to infiltrate the country. However, most attacks in the United States since 2002 have not been committed by recent immigrants. Terrorists like Omar Mateen – who killed 49 people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando Florida – are U.S. citizens who would not be subject to the ban. According to former Director of the National Counterterrorism Center and Cipher Brief expert Michael Leiter, although Trump’s focus on foreign attackers infiltrating the U.S. does tackle “one aspect of the threat, I have seen much less that addresses what is at least as important: the homegrown radicalization challenge we face.”

The new State Department guidelines appear to be a largely sensible security measure against an undeniable international threat. However, even relatively mundane new security measures implemented by the Trump Administration will hang under the cloud of the proposed travel ban until it faces the Supreme Court in October. In Rosenblum’s estimation, that ban “was an initiative in search of a counterterrorism rationale,” one that “essentially remains a plot to ban Muslims from traveling to the United States… Nothing is more insulting to a person’s dignity than being typecast exclusively because of their race, creed or color. The ban worsens this insult.”

Fritz Lodge is a Middle East and international economics analyst at The Cipher Brief. Follow him on Twitter @FritzLodge.