OPINION — When Edward Gabriel passed away unexpectedly this January, I lost one of my closest friends, but America—in the throes of coronavirus panic—lost a leader who would have helped us deal with the crisis with precision, speed, and compassion.

Ed was the deputy assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human services, a post he held since 2012 and carried over into the Trump Administration. Ed arrived in Washington on the heels of his third retirement. His most recent role was as Director for Global Crisis Management and Business Continuity at The Walt Disney Company, where I was his partner as Director for Global Intelligence and Threat Assessment. Before that he served under Mayor Giuliani as the deputy commissioner of the New York Office of Emergency Management, personally coordinating efforts near the World Trade Center after the towers were attacked and as they fell. Before that, he was a decades long veteran of the great FDNY, finishing his first career there as Chief Emergency Medical Services for the entire city.

He clearly knew what he was doing and saved countless lives in the process.

Ed came to Washington to make the country a better prepared place. As Disney’s intelligence chief, I worked hand in hand with Ed to protect the company, guests, and reputation from terrorists, criminals, natural disasters, medical emergencies, and accidents. Of all things, pandemics were at the top of our list. I had been in Hong Kong working for the US Government during SARS and learned about global health crises the hard way. Ed knew about them inherently. Together, we reviewed scenarios, table-topped exercises, and made contingency plans for the company to handle the mission. My job was to provide warning intelligence to avoid crises; his was to prepare for the worst, prevent what he could, and then rebuild what he couldn’t.

When we both moved from Los Angeles to Washington DC to take new jobs, we stayed in touch. Ed was proud of his mission, and of the federal government’s personnel, resources, and capabilities, which in his hands he intended to make more effective and efficient. He told me, for example, about a public health service reserve of volunteer physicians, nurses, and other medical professionals around the United States, ready to deploy on an emergency basis in service to their country. He spoke to me, with tears in his eyes, about how he sent mental health experts from this reserve to Sandy Hook in 2012 to provide support and counseling for highly traumatized first responders in the aftermath of that horrendous shooting; as a first responder himself, he knew someone had to take care of them as well as the victims. He told me how he sent the reserve and other experts to hurricane disaster areas in Houston and Puerto Rico, all on a moment’s notice. He refused a general officer commission in the Public Health Service because he felt he hadn’t earned such a high rank, despite his achievements. He told me how he would actively liaise, learn from, and teach, personnel from other departments and agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control, intelligence providers like my old haunts in the CIA, and just as important, at the state and local level, to better understand what mass disasters might take place and to build stronger relationships to make our response coordinated and effective.

America has lost a savior and a hero. I can’t help but think that if he were alive today, we would not see the confusion in action and messaging surrounding the Administration’s response to COVID-19. HHS and CDC would have demanded and won a much more prominent and active leadership role from the beginning. He would have vetoed the idea of sending untrained, ill-equipped HHS family liaison personnel to greet repatriated Americans in quarantine; instead he would have sent the well-exercised and expert public health reserve. He would have been hands on and insist on rearranging flight details to ensure infected victims were separated from the healthy. He would have spoken bluntly in his Brooklyn way to get things done and make sure they were the right things. And because he made the effort to build relationships throughout government, he almost certainly would have succeeded.

Ed was fond of repeating the 6P’s: “Proper Preparation Prevents Piss-Poor Performance.” I never forgot that. It would shock him to see the US Government’s response to this pandemic today, which is something that he and I and so many others have long discussed and prepared for. I can only think that without his strong leadership, we have forgotten all of the things we learned and planned to do. God bless you Ed. We’ll do better next time.

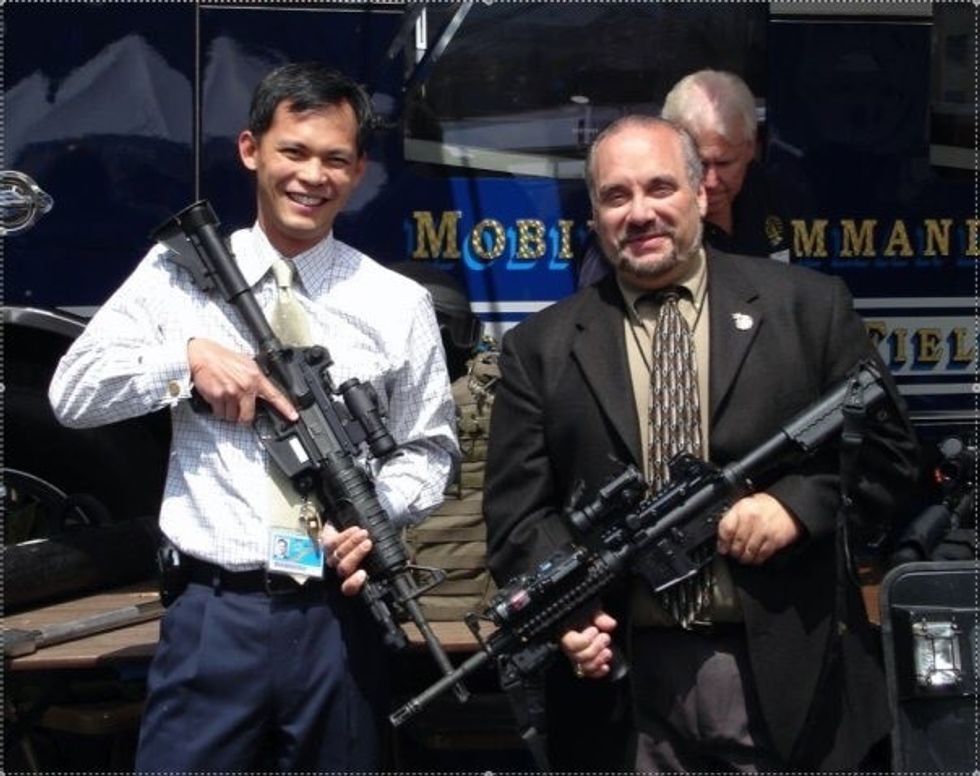

[caption id="attachment_32744" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

Rodney Faraon is a partner with business intelligence and strategy firm Crumpton Group LLC, a former senior analyst with CIA, and former founding director of global intelligence and threat assessment at The Walt Disney Company.

Read more expert-driven opinion, insights and analysis in The Cipher Brief