For decades, former secretary of state and White House chief of staff James Baker has touted his version of a salty military catchphrase as a good-government mantra: “Prior preparation prevents poor performance.”

That doesn’t necessarily apply to intelligence; even exquisite inputs from the CIA and other spy agencies cannot guarantee that policymakers will perform well at high-stakes events like summits. A whispered maxim in CIA is, “You can lead a policymaker to intelligence but you can’t make him think.”

Yet intelligence should be a part of every step of planning and executing meetings between US leaders and their counterparts—from the first inklings of a summit to the face-to-face session itself—to raise the odds of achieving favorable outcomes.

We don’t know how Top-Secret information has contributed to President Trump’s preparation for his forthcoming one-on-one meeting with Russian President Putin. But our experience supporting past presidential summits tells us just how important intelligence assessments usually are, and should be, at each level of the process. Such a hand-in-glove intelligence-policy relationship truly increases the chances of summit success while decreasing the odds of a foreign policy disaster.

Let’s start before any meetings have even been announced. Should there be a summit at all?

Ideally, policy customers speculating about the possibility of a get-together have already been using intelligence about everything from the foreign leader to the political climate in his or her country to the state of play within international conflict zones to decide whether the president is likely to make headway on national security goals through face-to-face talks.

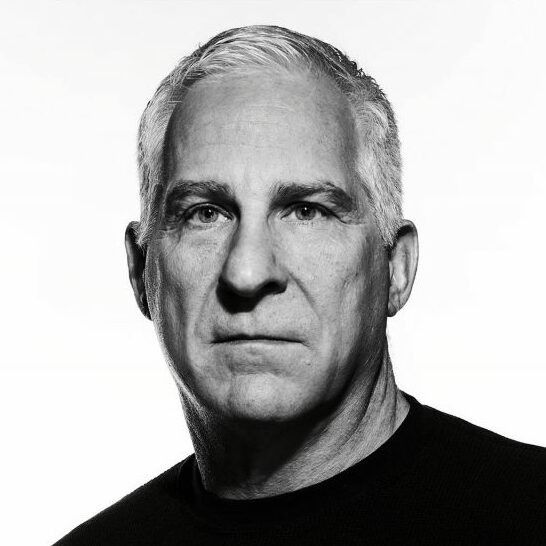

David Priess, Former Daily Intelligence Briefer, CIA

"In the White House planning processes that we had access to during our careers, no senior officials considering a summit would just “wing it” without fully examining the likely costs and benefits of an in-person meeting—and intelligence always played a role in that calculation."

In the case of this US-Russia summit, the president’s meeting with Putin seemed to pop up rather quickly. We just don’t know the extent to which intelligence assessments factored into his decision to sit down one-on-one with the Russian leader.

Some former intelligence officials have implied that they would have advised the president to think very carefully before making such an announcement. For example, Steven Hall wrote in The Cipher Brief's 'Moscow Station' column earlier this week , “Russia has much to gain, and from my perspective, the United States profits little, if at all.” But the president, not some adviser, ultimately calls the shots. This summit was on.

Once a meeting is on the books, the intelligence role traditionally shifts to preparing officials who are tasked with setting up the details as well as those who will be participating. Weeks and often months before departing, the president and his inner circle of likely summit attendees usually start receiving strategic intelligence analysis related to the goals of the session. But they are far from the only ones getting specialized support.

In a well-functioning administration, members of the entire national security bureaucracy feed ideas about summit objectives and potential concerns up through their own institutions and into the inter-agency process to inform and influence decisions about what the US government wants to get out of the session.

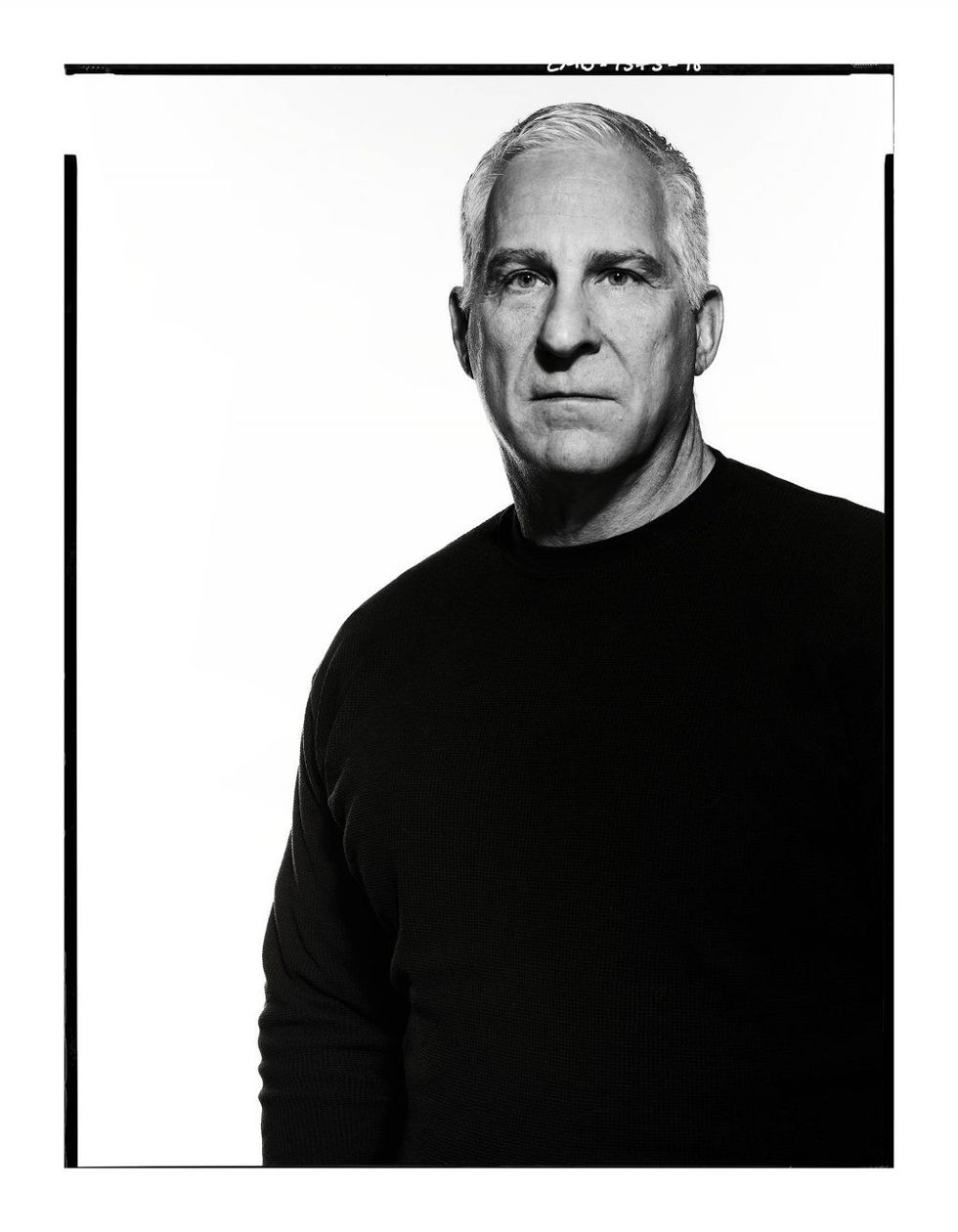

John Sipher, Former Member, CIA's Sr. Intelligence Service

"All of those officials, too, are informed by intelligence—including from diplomats and clandestine collectors around the world, who provide reporting on how various countries and key officials view the summit from their unique perspectives."

Surely, any administration will want insight into how our allies and adversaries see the challenges and opportunities of the meeting, and will seek to understand how they might react to various outcomes.

To prepare this wide array of customers—as the intelligence community calls them—classified inputs might include everything from deep background papers on the politics, economy, and national security strategy of the country in question to briefings about the policies and personalities of the interlocutors whom the president and other Americans will encounter.

Particularly useful, especially as the date of the talks approaches, are profiles of foreign leaders that intelligence officers build to give summit-goers every possible advantage during summit conversations. These products cover much. Analysis of counterparts’ policy goals helps US officials identify possible points of conflict—and potential areas of common ground. Assessments of counterparts’ bureaucratic allies and opponents enable skillful US officials to manipulate such relationships for the benefit of Washington’s policy. And intelligence about counterparts’ educations, families, and hobbies gives US officials fodder for small talk and crucial rapport-building.

As the summit countdown gets from weeks to days away, various intelligence sources and quick-turnaround analysis inform the president and other attendees about shifting foreign goals and tactics for the meetings. Adjustments to talking points, negotiating strategies, and conversational tricks can be made even as the president is about to greet his counterpart.

John Sipher, Former Member, CIA's Senior Intelligence Service

"During the summit, breaks allow the president to confer with advisers and shift tactics—based not only on what has occurred in the face-to-face discussions but also on up-to-the-minute intelligence information, obtained as contemporaneously as possible."

This all describes how intelligence prep for a summit should go. In cases like Jimmy Carter’s summitry with Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menachim Begin that led to the Camp David Accords and Ronald Reagan’s and George Bush’s meetings with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, enough time has passed to get a sense of both such intelligence support and the policy outcomes informed by that support. What about now?

We lack reliable reporting on just how much the shortened timeframe for this summit with Putin has affected the intelligence community’s ability to provide useful material to the president and his top advisers. Our experience tells us that under pressure, intelligence officers step up and do whatever needs to be done to get necessary reports and profiles to the men and women in the policy agencies tied to the summit.

David Priess, Former Daily Intelligence Briefer, CIA

"We have high confidence that objective, timely, and hopefully accurate intelligence information is right now getting to all relevant policymakers—and that most of them have used it in crafting their policy papers, memos, and other material for the next level up."

Whether the president himself has absorbed the analysis that he has received via the President’s Daily Brief and other intelligence products remains another matter.

On issues touching on Russia—most notably, but not exclusively, election interference—his policies and comments have not aligned with any other president’s actions and statements, implying either a rejection of intelligence judgments or a radically different interpretation of the information he is receiving. Like the famous Seinfeld episode where George Costanza convinces himself that he should do the opposite of his initial instincts, Trump appears to take pleasure in defying conventional advice.

Either way, this suggests preparing this president for this summit ranks among the toughest challenges intelligence officers have faced in seven decades of supporting policy.

What comes out of the summit will reflect more about the president’s policy than about the intelligence that has been put forward to inform it. After all, prior intelligence preparation may permit positive summit performance, but it can’t assure it.