Exclusive Subscriber+Interview — This week's NATO Summit in Vilnius may have fallen short of the clear path to membership that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has been requesting for the past several months, but the 31 member nations did get some important business done.

The Cipher Brief expert and former Ambassador Douglas Lute, who served as U.S. Permanent Representative to NATO, said there were four main challenges that the alliance had to deal with this week. And by Wednesday afternoon, at the conclusion of the final day of this year's summit, it seemed very close to achieving all four.

Topping Lute's list of the most important NATO business this week:

- Leadership: With the war in Ukraine raging, the alliance decided to extend the leadership term of Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, whose contract was extended another year in June, effectively giving the former Norwegian Prime Minister a full decade atop the alliance.

- Defense Plans: In what constitutes a reflection of just how serious NATO has become about the prospect of a Russian attack, leaders outlined comprehensive military plans that, for the first time since the Cold War, specifically detailed how the group would react to an attack on NATO soil.

- Sweden: In a show of unity, particularly with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's initial hesitancy to approve Stockholm’s bid to join the alliance, the Nordic country eventually won Erdogan’s support, only to have it made conditional again on Wednesday, with the Turkish leader saying that Sweden actually needed to take additional steps to win his country's parliamentary support. The Turkish legislature is set to take up the issue this fall.

- Ukraine: While NATO declined to offer Ukraine a formal invitation or timetable for Ukraine's entry into NATO, the alliance did offer Kyiv a framework for military and financial support, intelligence sharing, and a vow of action, should Russia attack again, following the conclusion of the current war.

The Cipher Brief sat down with Ambassador Douglas Lute for an in-depth conversation about NATO, its security goals, and the accomplishments at this week’s summit. Our conversation has been lightly edited.

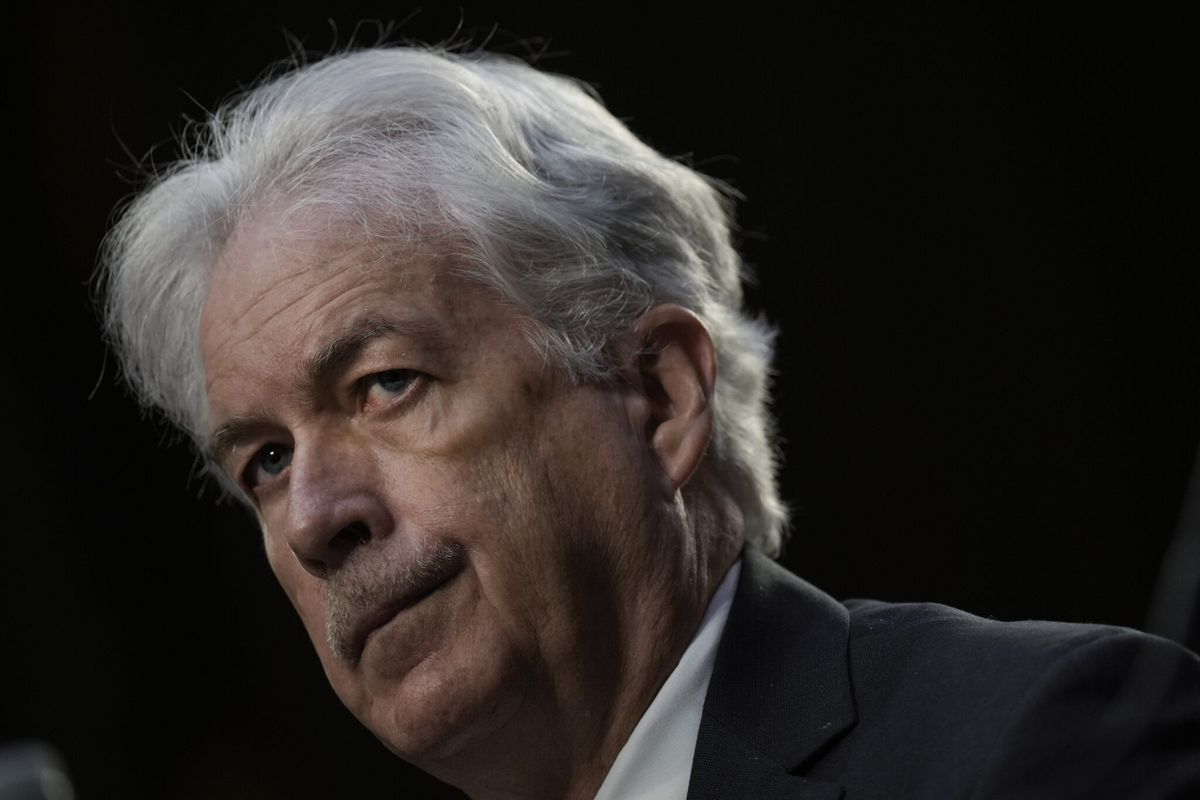

Douglas Lute, Former Lieutenant General and Ambassador

Former Ambassador and Lieutenant General Douglas Lute, is the former U.S. Permanent Representative to NATO. Appointed by President Obama, he took the post in 2013 and served until 2017, during which time he designed and implemented the Alliance’s responses to security challenges in Europe. A career Army officer, in 2010 Lute retired from active duty as Lieutenant General after 35 years of service. In 2007, President Bush named him Assistant to the President and Deputy National Security Advisor to coordinate the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2009, he served as a senior official in the Obama White House.

The Cipher Brief: There were a few unexpected twists during this week's summit. What surprised you the most?

Lute: If we would have had this conversation two weeks ago, I would have offered that there is really only one thing that NATO needs to get out of this summit and that is an image of solidarity, unity and cohesion. No matter what the challenge is in a particular summit, everything is displayed in one image: the so-called 'family photo', where you've got all 31 leaders, plus the Secretary General, smiling. That's the image you want from a NATO summit. And this time, there were at least four significant challenges to unity. The first was deciding who would serve as the Secretary General.

They cleared the deck on that one by taking the easiest approach, which was to extend Stoltenberg for a fourth time, and essentially give him a 10th year in office. He became Secretary General in 2014, when I was in the chair for the US. He'll see us all the way through the Washington Summit next year. The Alliance was able to show unity and cohesion in that decision. But it's nonetheless a compromise. There were others who had candidates. The UK wanted Ben Wallace, the Balts wanted a Balt. But at the end of the day, they found consensus, and they took what I think, is the obvious path in extending Stoltenberg's service.

The second issue was that they needed to gain agreement for approval at head of state level on these new defense plans. This is NATO's wonky bureaucracy. But in this case, it's significant because now, for the first time, since the end of the Cold War, NATO actually agreed to defense plans for its three geographic areas, one for the North, one for the Center and one to the South. For each of those three plans, there are specific national forces that are allocated to support those plans. This is a level of detail, a level of specificity that the Alliance hasn't had since the end of the Cold War.

Since then, they essentially said, "Hey, look, if we need you, we'll call you. And we'll put it together on the fly,” in an ad hoc basis. Ever since the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014, they had only modest forces. A battalion in a country was the model after 2014; a very modest forward presence, which essentially represented a tripwire in the Baltic states and Poland. But these were reinforced battalions. And then behind that, there was an upgrade in NATO's response forces. The idea was modest forward presence, essentially serving as a trip wire, conceptually, backed up by rapid reaction, much larger formations that could come in the face of an emergency. That model served us from 2014 until today.

Looking for a way to get ahead of the week in cyber and tech? Sign up for the Cyber Initiatives Group Sunday newsletter to quickly get up to speed on the biggest cyber and tech headlines and be ready for the week ahead. Sign up today.

And now we have full-fledged defense plans, North-Center-South with specific national assignments for each of those plans. The Germans know where they are supposed to go, with what capabilities, what kinds of forces, and on what kind of timeline. And likewise for the US. All 31 allies now have their homework, they have their assignments. But the interesting part of this is that those sorts of specific plans are expensive. So, the second big issue NATO must contend with, is what do you do for those defense investments that are now required in order to make these plans credible? And can you get beyond what we last said about defense investments? So again, this takes you back to 2014. Obama's in the chair for the US, they signed the Defense Investment Pledge, which said that in a 10 year span, from 2014 through 2013, all allies would aim to move toward a 2% of national GDP pledge.

That's a big deal because there are only 11 of the current 31 allies who meet that standard today. Essentially, two thirds of the alliance has work to do in terms of defense spending. Now, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the last 18 months of war in Ukraine, provide a pretty big impetus and a reminder to NATO that things like Russian long range cruise missiles, the danger of the Black Sea Fleet, the Baltic Sea Fleet, which is there, and also armed with cruise missiles, that the missile capability based on the ground, present threats.

They're not imaginary, they're not hypothetical. They're actually being played out where they're being witnessed in Ukraine today. Capabilities like integrated air and missile defense, which has long been on NATO's wish-list. Now, there's a real demand signal here that NATO needs to get serious about this.

And the most sophisticated air and missile defense system in Europe today is in Ukraine. NATO's got to be left saying, "My God, we better get serious about this ourselves." And while the Russian Ground Force has been ground down in Ukraine, its Air Force has not, and its missile forces have not. And its cyber forces, its sub-conventional forces have not. The second issue of plans coupled to resources is the second challenge for Vilnius. And it seems like they've got the narrative right. But in this case, the deliverable will come after Vilnius.

For example, as the largest economy in Europe, do the Germans actually move on an appropriated funds basis to 2%? And we'll see, that's not entirely clear to me that they will. That's contentious issue number two. Number three is Sweden. Two weeks ago, I actually forecasted that we would not get across the line with Erdogan. And then Erdogan pulled an Erdogan, he surprised us. And in this case, a pleasant surprise. But the point is that we're now back on track with Sweden. And I would say, in the coming couple months, we'll probably see Sweden as the 32nd ally. And of course, the remaining drama here is that this is now has to go before the Turkish parliament. And then you have next door [Hungarian President Viktor] Orban, and the Hungarians watching this closely because their parliament's got to ratify the accession agreement as well.

The Hungarian parliament, I believe, is out of session until the early fall. That box is at least half checked. Now, number four won't surprise you, that's Ukraine.

The Cipher Brief hosts expert-level briefings on national security issues for Subscriber+Members that help provide context around today’s national security issues and what they mean for business. Upgrade your status to Subscriber+ today.

What was the alliance going to say about Ukraine? And I think this fourth issue is the one where while they reached a compromise as represented in the text to the communique, it's probably of the four issues, the compromise that's least satisfying. And they got there, they did agree the text, but it's either too much or too little for most of the allies.

Ukraine got a burst of commitments on sustaining and even increasing military assistance. The French committed to air-launched long range precision strike system similar to the one that the Brits provided, which will help Ukraine reach deeper into the occupied territories. That's significant. And we'll see what actually comes out in terms of other bilateral or sub-alliance, coalition of the willing-like commitments. That's good news. That was essential. But that was not a heavy lift. We're already doing that. Of course, Zelensky wanted a much more defined commitment to how he'll move towards membership and by when. Frankly, he did not get much in that regard. The paragraph on Ukrainian membership is more wordy than the 2008 Bucharest communique from 15 years ago.

It's not substantively much different. The last sentence says it all, and essentially says, Ukraine will become a member when all allies agree and the conditions are that. Not a big surprise. In fact, it's essentially a restatement of what the treaty says about adding new members. And the treaty itself, Article 10 of the treaty says that there are three criteria for new members. They have to be agreed unanimously. We got that. We just had a demonstration of that with Turkey and Sweden. Number two, they have to be able to contribute to the collective defense. I would argue that Ukraine's checked that box. In my assessment, they have the most capable ground force in Europe today. Who's going to compete? And nobody competes with combat experience.

Ukrainians have not only demonstrated that they can defend Ukraine, but that they have the capacity contribute to the collective defense. They can help others. And then the third one's the catch though, and this is the one about democratic values. The treaty says that an aspiring state must represent the values, the principles of the alliance. And those are usually reported as democracy, individual liberty and rule of law. Here, I think with a straight face, you can make the case that Ukraine is an emerging democracy. Even before the war, Ukraine had shortfalls in terms of those democratic principles. And now they're operating under martial law.

The real question is what happens to Ukraine, democratically, once the war is over and they can revert to a reform agenda, a democratic reform agenda? And essentially, what this communique says is that remains, democratic values remain a condition of membership. And Ukraine did get. And this I think was very much the Biden administration focal point with regard to Ukrainian membership. And remember that, Biden said, they have work to do with democratization.

This was his indirect reference to these Democratic principles. Most of the debate about these conditions hinges on the common observation that Ukraine is clearly capable, militarily, and skips past this second, or in my counting, the third criterion, which is this question of democratic values. And just essentially says, look, we're not going to give Ukraine a pass on democratic values.

The Cipher Brief: How do you think that NATO, which for the most of its existence is focused on kinetic warfare, is transitioning to the kinetic-cyber hybrid. Does a cyber attack on one mean a cyber attack on all?

Lute: NATO's done a number of things given the last maybe 10 years of experience on cyber. And this got an impetus after Crimea and so forth, because of the cyber-attacks that preceded the 2014 assaults in Crimea and the Donbas and so forth. And then even before that, I think it was 2007 that Estonia, a NATO ally, suffered a significant shutdown of internet services. And of course, Estonia's government runs on the internet. It's probably the most cyber savvy of all the allies. The alliance has done a number of things. First of all, it declared cyber a domain. It did not declare that in order to oversee this domain, it would create a command, but it did register the importance of cyber. It also took a policy decision, I believe in the 2014, that a cyber attack may trigger Article 5.

And this was a bit of an update of the 1949 treaty, which says, Article 5 is triggered by an armed attack. That leaves a pretty gaping hole. And the ideal was, Let's update by way of a policy decision, the treaty, the language in the treaty that then covers a cyber attack. And then it goes on to say, We won't define exactly what level of cyber attack could trigger Article 5. We'll judge that by the effects of the attack. So, by extension, you can imagine that if a cyber attack resulted in fatalities and a major damage to physical infrastructure, if it shut down the hospital system and people died as a result, then you would have effects that somewhat are parallel to the effects of an armed attack. This policy gap has been somewhat closed by way of this decision.

I think that cyber in particular is one of the areas in which NATO partnership with the EU should be emphasized because most EU member states are NATO allies. It makes sense that NATO and the EU collaborate on national standards for member states so that member states don't have one set of standards for NATO and another set of standards for the EU. Because much of the threat, the cyber threat, the cybersecurity threat, is against dual purpose infrastructure.

If you're going against the mass communications grid, that obviously is a digital platform, a digital capability, but it serves both the civil and the military realm. Same with transportation, the transportation network, the hospital networks. So, much of this infrastructure is dual purpose. So, I'd offer that this is a place of ripe for cooperation and coordination between NATO and the EU. And they have done some of that, but I think there's much more work to be done. One of the lasting effects coming out of the war in Ukraine will be that the three-tiered military capability structure of Russia will have suffered major damage, especially in the conventional tier.

The nuclear tier stands intact. The conventional tier of Russian military capability is suffering heavy attrition in Ukraine. Frankly, their army is being just set back a generation in Ukraine. And then below that, you have the sub-conventional cyber misinformation, disinformation, election interference, energy intimidation, and all those capabilities down below conventional. When Russia comes out of this, what will be left?

They'll have the nuclear capability left. They'll have a huge rebuilding chore on their hands for conventional capabilities, especially conventional ground capabilities. And they'll have intact the sub-conventional. The challenges going forward, the threats going forward from Russia as they try to rebuild their conventional forces will be sub-conventional.

The reality is the Russians are not going to in 10 or 20 years, be able to assemble 150,000 ground troops or 200,000 ground troops somewhere on NATO's border and attack with tanks and helicopters and all that stuff. They just won't. That stuff's being destroyed in Ukraine. But that doesn't mean Russia's going to become complacent. I think they're going to revert increasingly to sub-conventional. Hybrid is here to stay.

The Cipher Brief: Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky was calling for a clear path to NATO membership and he didn't get it. What do you expect will happen next?

Lute: Zelensky is the master strategic communicator, how he narrates this, not only to his people, but also to the people who are providing him a lifeline, the 31 allies and more who are providing him this, the means by which he can defend Ukraine is really important that he gets this right. This may be among the most important narratives that he has to craft and communicate. Before he read the communique language, he tweeted that it was absurd. But my guess is that he will moderate that, and how he moderates it and how effectively he communicates gratitude for the continued support. He did get something out of Vilnius and he doesn't want to go home empty handed. When I was in Kyiv, one of the conversations we had repeatedly, was that you have to be ready for what's going to happen. And if it's clear that some instantaneous pledge to membership is not going to happen, then quit asking for that. Because otherwise, you back yourself into a corner, a communications corner, now, at the end of the Vilnius Summit. That's why there's still some drama to play out here in terms of what how he actually casts this decision coming out of Vilnius.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspectives and analysis in The Cipher Brief