OPINION — "For purposes of National Security and Freedom throughout the World, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity.”

That was President-elect Donald Trump in a statement on December 22, made while announcing that he plans to nominate Ken Howery to serve as the next U.S. ambassador to Denmark.

Greenland is the world’s largest island, covering 840,000 square miles, more than 80 percent of which is covered by an ice cap or smaller glaciers. With a population of near 60,000, Greenland was a colony of Denmark for some 300 years, but was granted home rule in 1979. Greenland’s people voted for self-government in 2008, which the government in Copenhagen approved, while retaining control of Greenland’s defense, foreign and monetary policies.

Danes and Greenlanders alike have heard statements like Trump’s before, and, no surprise, Greenland’s Prime Minister Mute Egede responded to Trump by saying, "Greenland is ours. We are not for sale and will never be for sale.”

The U.S. and Greenland – a history

Trump and the American people should recognize there is a long and complex 80-year history of U.S. military activities in Greenland involving air and naval bases, weather stations, nuclear weapons, and even a secretly built underground facility, put in place to protect the U.S. homeland. I review some of that history below.

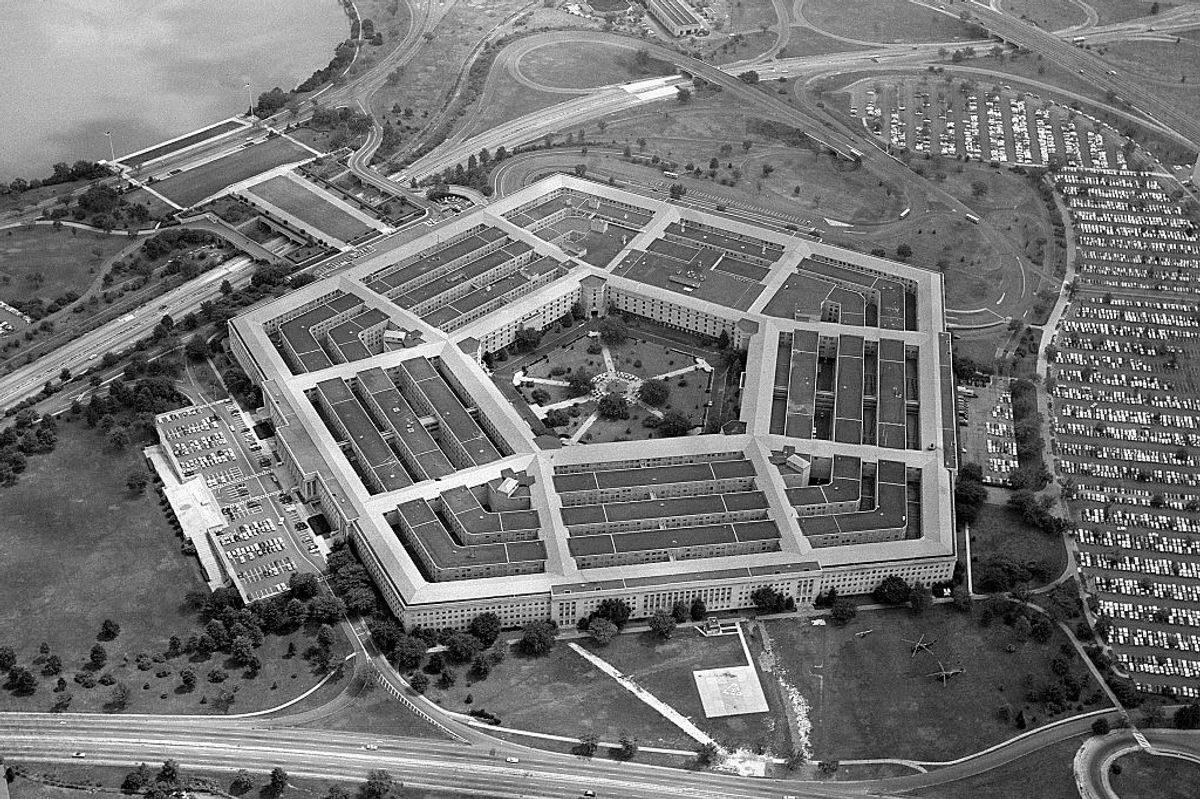

But first it’s worth looking at the importance today of the varied military operations the U.S. is carrying on in Greenland at Pituffik Space Base (pronounced beee-doo-FEEK), formerly known as Thule Air Base.

It is America’s northernmost base, located in the middle of nowhere, 750 miles north of the Arctic Circle, and 947 miles south of the North Pole on Greenland’s northwest side. Pituffik is locked in ice for nine months of the year, but the airfield is open and operated year-round. The nearest town is 75 miles to the northwest.

From this base the U.S. Air Force and Space Force personnel carry out ballistic missile early warnings, missile defense, and space surveillance missions supported by what the Space Force described as an “Upgraded Early Warning Radar weapon system.” That system includes “a phased-array radar that detects and reports attack assessments of sea-launched and intercontinental ballistic missile threats in support of [a worldwide U.S.] strategic missile warning and missile defense [system],” according to a Space Force press release.

The same radar also supports what Space Force said is “Space Domain Awareness by tracking and characterizing objects in orbit around the earth.”

The phased-array radar is operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week by U.S. and Canadian military personnel and contractors. The system’s antennas do not move, but the radar’s thousands of beams are electronically steered to programmed locations covering two-thirds of the horizon.

Also operated out of Pituffik Space Base is one of seven worldwide Remote Tracking Stations in the Satellite Control Network (SCN). Run by Space Force, SCN provides support for the operation, control, and maintenance of a variety of Defense Department and some non-defense satellites. The Greenland automated tracking station, Space Force said, “allows contact with polar orbiting satellites 10-12 times per day…[and] provides telemetry, tracking and commanding for communication with surveillance satellites of the highest national priority; communications, navigation and weather satellites; and NASA missions. It also…conducts more than 15,000 satellite contacts per year with a 99.3 percent success rate, 24/7.”

The Pituffik Space Base population, which can total over 600, includes fewer than 200 active-duty U.S. Air Force and Space Force personnel. The majority includes representatives from other government agencies and private contractors working to support the Pituffik Space Base military mission, plus Danish Arctic Command personnel in the Danish Liaison Office; Danish Police; some Canadian military and researchers funded by international agencies.

As in the past, today’s U.S. military activities in Greenland have as their primary purpose defense of the American homeland. Given that situation, it’s been a bargain for Washington to have had the use of property in Greenland without paying rent, as the U.S. does, for example, for a similar, multi-use base in the South Pacific Marshall Islands.

Protection of the U.S. homeland was certainly the purpose more than 80 years ago, in the fall of 1941, when the first U.S. air base was built in Greenland near the end of Sondre Strom Fjord, 30 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

Circumstances were quite different then. Hitler’s troops had seized Denmark in April 1940. Greenland’s governors and the then-Danish Ambassador to the U.S. formed councils which, as an unofficial government-in-exile, signed an agreement on April 9, 1941 with then-Secretary of State Cordell Hull, which permitted the U.S. to operate military bases in Greenland "for as long as there is agreement" that the threat to North America existed.

A critical mine

At that time, there was another reason for U.S. interest in Greenland — the cryolite mine at Ivittuut, located near the tip of Greenland. Cryolite is necessary to the electrolytic process that produces aluminum, and this mine was the United States’ only commercial source of the mineral required for producing aircraft.

During World War II, some 500 U.S. soldiers guarded the mine, and big guns were placed in strategic points for protection. The U.S. Navy also built a naval base three miles away and the U.S. Coast Guard built a base across the fjord from Ivittuut, holding hundreds more soldiers. With America’s source of strategic cryolite secured, President Roosevelt requested military appropriations from Congress, including the industrial capacity to build at least 50,000 aluminum-skinned aircraft per year.

After a Nazi submarine sent a torpedo toward a U.S. Navy destroyer, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, during a September 11, 1941 Fireside Chat, declared, “The United States destroyer, when attacked, was proceeding on a legitimate mission…There will be no shooting unless Germany continues to seek it. That is my obvious duty in this crisis. That is the clear right of this sovereign Nation. This is the only step possible, if we would keep tight the wall of defense which we are pledged to maintain around this Western Hemisphere.”

In 1946, the post-war U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted to secure military rights in Greenland from Denmark, which eventually led to a Truman administration offer, similar to Trump’s. It came during a December 1946 meeting in New York City between visiting Danish Foreign Minister Gustav Rasmussen and Secretary of State James Byrnes. After discussing other security arrangements for Greenland, Byrnes told Rasmussen that an outright sale to the United States would be more satisfactory. The U.S. would pay $100 million. Rasmussen took the proposal, but the Danes never acted on it.

Greenland and the Cold War

The 1949 founding of NATO led to an April 1951 United States-Denmark joint defense agreement for Greenland, which allowed the U.S. to operate bases in Greenland for NATO defense activities. The air base at Thule (now Pituffik) was built in 1951–52, and the indigenous population was relocated to other settlements. Other bases were built at Narssarsuaq, and Sondestrom. In the context of the Cold War, these bases provided refueling points and operation sites for intermediate-range B-47s and long-range B-52 strategic bombers.

Thule, according to a SAC press release, “is at the precise midpoint between Moscow and New York…Strategic Air Command bombers flying over the Arctic presented less risk of early warning [to Moscow]] than using bases in England. Defensively, Thule could serve as a base for intercepting [Soviet Union] bomber attacks along the northeastern approaches to Canada and the U.S.”

Additionally, the U.S. deployed radar stations in Greenland to maintain a Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) and a Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, which would give the United States advance warning of a Soviet nuclear attack.

In 1959, the U.S. also secretly began building a ballistic missile base beneath Greenland’s ice layer, 150 miles east of the Thule Base. Powered by a portable nuclear generator and called Camp Century, it was built to host up to 200 soldiers, provide year-round accommodation, and upon expansion would be capable of storing up to 600 ballistic missiles. The cover story was that it was a demonstration for constructing affordable ice-cap military outposts and a base for scientific research.

Called, Project Iceworm, the original Army plan called for deploying the 600 missiles, in trenches four miles apart, and build 60 Launch Control Centers. The “Iceman” missile was to be a modified version of the Minuteman ICBM, but with only two stages and a range of 3,300 miles, enough to hit targets in the Soviet Union.

In the end, the Army found the Greenland ice sheet was too unstable to support the project, whose tunnels could collapse at any moment. Project Iceworm was officially canceled in 1963, but not totally abandoned until 1967, when the nuclear reactor was removed. Today the remains of Camp Century survive under roughly 100 feet of snow and ice.

Beginning in 1961, SAC began flying a mission called the Thule Monitor. This was a single B-52, carrying four live thermonuclear bombs, that would orbit continuously near the Thule Air Base’s BMEWS system. The Thule Monitor B-52’s purpose, according to a SAC document, was to “be in a position to determine quickly the nature of any communications failure between the [BMEWS] site and warning centers in the United States,” and “race toward the Soviet Union in case of an attack on the station.”

On January 21, 1968, a Thule Monitor B-52, armed with four B28 thermonuclear bombs, developed a cockpit fire, forcing its crew of seven to bail out. The bomber crashed on the ice in a narrow fjord less than eight miles from the Thule Air Base runway. Six of the seven crew members were rescued within hours; one died from an accident exiting the airplane.

When the B-52 crashed, the conventional explosives in three of the four bombs exploded rupturing their nuclear payloads and thus dispersing radioactive material, including plutonium and uranium, over a wide one-mile-by-three-mile area. The nuclear payload of the fourth bomb, which probably went through the ice to the water below, was not found.

Cleanup operations under U.S. and Danish supervision, were undertaken under the code-name Project Crested Ice to remove blackened, contaminated, ice and wreckage from around the crash site. Some 147 freight cars of radioactive waste were shipped back to the U.S.

One result of the crash was that the U.S. halted the practice of having its in-flight strategic bombers carry live nuclear weapons. Instead, SAC nuclear-armed bombers were kept on 15-minute alert and on runways ready to take off.

The U.S. has been operating in Greenland under the 1951 agreement with Denmark, which was amended in 2004 to reflect Greenland’s new status as a part of Denmark, and no longer a colony. In addition, the 2004 change said, “The Government of the United States will consult with and inform the Government of the Kingdom of Denmark, including the Home Rule Government of Greenland, prior to the implementation of any significant changes to United States military operations or facilities in Greenland.”

In the aftermath of Trump’s December statement that the U.S. needed to own Greenland, Prime Minister Egede, in his January New Year’s speech, talked of his desire to pursue independence from Denmark. "It is about time that we ourselves take a step and shape our future, also with regard to who we will cooperate closely with, and who our trading partners will be," Egede said.

Under a 2009 agreement with Denmark, Greenland has the right to declare its independence through a referendum, which Egede hinted could be held as early as April in conjunction with the island’s planned parliamentary elections.

President-elect Trump may want to own Greenland when he once again becomes the leader of the world’s richest and most powerful country, and its 335 million citizens. But in the end, he may have to bow to the wishes of Egede, the prime minister of a much smaller, weaker, poorer, and currently icebound entity, but a property that for eight decades has been key to the defense of the U.S. homeland.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief