In the mid-2000s, I was working as an Executive Producer at CNN’s global headquarters in Atlanta. Like many reporters, I was looking for post 9/11 stories that hadn’t been told, stories that had some kind of lasting impact on society as a whole, and I was looking for people who were at the center of those stories.

I had had a fairly interesting career, at least to my standards. I had the enormous privilege of traveling the world, had sent myself as a freelance journalist, into war zones and had sought out the people and issues that were shaping the world we were living in, which at that time, focused a lot on war.

I thought I had seen a lot, but in 2004, I was haunted by the images of Americans being dragged through the streets of Fallujah, brutally murdered, their bodies hung from a bridge. The images never left me, and millions of Americans who saw them on national television, still remember them. The horrific attack prompted many to ask what was happening in Iraq? And I was no different. That single incident started a string of questions for me where every answer led to more questions. What were Americans - who were not active military - doing in a place like Fallujah? What in the world would draw them there for logistics work (in this case, accompanying food supplies), and who was in charge of making sure they were safe?

I pulled together an excellent CNN team of journalists and we went to meet the man behind Blackwater, Erik Prince. The resulting piece that aired on CNN was excellent but wasn’t nearly the whole story. As I had often found in my television career, not every story could be told in minute increments.

In 2006, Prince’s company had come a long way from Fallujah. By finding a niche that the military couldn’t fill, he launched an enterprise that provided armed protection details in some of the world’s most dangerous places. When I visited with the CNN crew, his company had just been awarded a multi-billion contract by the U.S. State Department to provide even more of that work in Iraq.

I’ll spare you the details of the rest of the story, which – if you care to read them – you can find in Master of War: Blackwater USA’s Erik Prince and the Business of War (Harper) 2009. This story is about what it took to tell that story. I was a career journalist who had always had aspirations of writing a book someday but didn’t have a clue how the publishing world worked. I had spent most of my journalism career in television and radio. I started looking into it, and like a lot of aspiring authors I talk to today, found that the process was daunting. ‘Good luck finding an Agent,’ friends had told me. ‘And when you do, good luck finding a publisher.’ I’ve never been one to shrink in the face of a challenge, but I must admit, I was worried. I started asking friends and acquaintances who had written books how they had done it and I found that there was no magic bullet, no one recipe, other than, ‘Start with a good story.’

One friend was kind enough to introduce me to his Agent in Hollywood. Hollywood wasn’t an intuitive place for me, but a leading talent firm, Endeavor, had branched out of movies and television and was competing with the big publishing houses in New York. I had my first call with Richard Abate sometime in 2006, and lucky for me, he loved the story. He signed me and didn’t waste a second lining up meetings with potential publishers. While I had never met him in person, he seemed like everything I would have imagined a high-powered Agent to be: in control, well-connected, and not one to waste time on niceties. Within what I think was a two-day period of time, I had interviews with several publishers and they had come back with offers. We had a deal by the end of the third day and I knew I’d better get writing. I also knew that my experience was a unicorn experience. It was nothing like what I had been warned about. It was freak thing, I told myself, a combination of luck, the right introduction, and of course, a great story to tell.

But that’s not the case for other talented authors, and I know a lot of them. Particularly in the world of espionage, I am often sent stories to read by friends and acquaintances who are trying their hand at this storytelling thing in the same way that I did but navigating the rest of it is even harder these days when competition for shelf space in a brick and mortar store is literally like fighting ghosts. Authors who started profitable book series and have passed away, today live on through new authors brought in to continue those stories. E-Publishing and Self-publishing seem like great alternatives, but they really aren’t great at marketing and selling books.

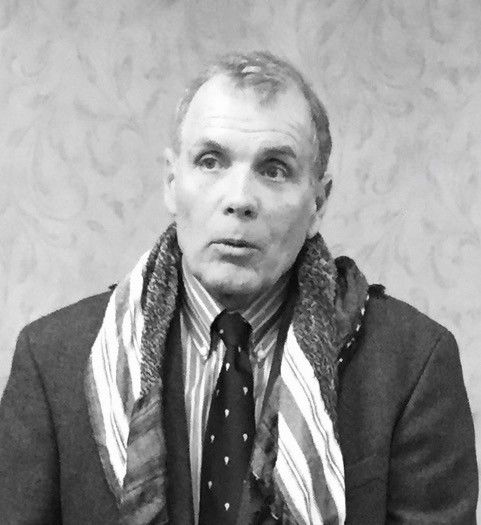

I recently tracked down Richard Abate, my Agent in New York and asked him to help me understand how the market has changed, and to give me some practical tips that I could share with you.

Let me tell you something about Richard, who is now an agent with 3 Arts Entertainment and has worked with some of the best in the business (and then also people like me). Richard is blunt, to the point, doesn’t waste time, and doesn’t believe in using too many words when just a few will do. He has worked with top creative talent like Tina Fey, Mindy Kaling, Issa Rae, B.J. Novak, Guillermo Del Toro, and others. He also represents authors in a variety of genres, everything from true crime (he represents DEA Agents Andrew Hogan who captured El Chapo (HUNTING EL CHAPO)) to literary writers like PEN/Faulkner winner Kate Christensen, Sana Krasikov, and Oscar Casares. When my book was published in 2009, fiction was king. Today, things have changed, and I asked Richard to answer a few more of my questions to help you navigate the publishing world today.

Kelly: How alive and well is the spy genre these days?

Abate: The genre is as old as books. A great spy story will always sell, will always find a home. Like anything else, it is about the writing first and foremost.

Kelly: Which national security-focused books typically sell better, fiction or non-fiction?

Abate: In quiet times, fiction always sells better. In turbulent times, such as we are living, non-fiction is always king. We are living the greatest spy story ever told in President Trump. Fiction feels thin compared to the real world right now, so the bar is very high to break through. Non-fiction is strong but stories from places like Afghanistan and the war on terrorism feel a bit tired. It’s tough to find the right mix right now.

Kelly: Some people say that finding an agent is harder than writing a book. What advice do you have for aspiring authors in this genre?

Abate: Write a great letter! Take your time with it. It’s the first thing I read. Make sure that first chapter really sucks the reader in. Reference some of the agent’s successes when corresponding. Know why you picked this person.

Kelly: What kinds of books in this genre are getting the attention of publishers these days?

Abate: Authenticity. Generally bigger stories, with bigger stakes.

Kelly: How much of an impact is self-publishing having on the genre (or the industry at large)?

Abate: I don’t think it does in a big way. It allows for some smaller stories to find a home, but rarely translates into big sales.

Kelly: What is the most annoying thing for a book agent?

Abate: People who don’t take ‘no’ for a ‘no’.

Kelly: Alternatively, what is music to the ears of a book agent?

Abate: Music to my ears is great writing, interesting storytelling, and something that works for multiple platforms.

So there you have it aspiring writers. I’m quite sure you have all the advice you need. Now, you just need to write.