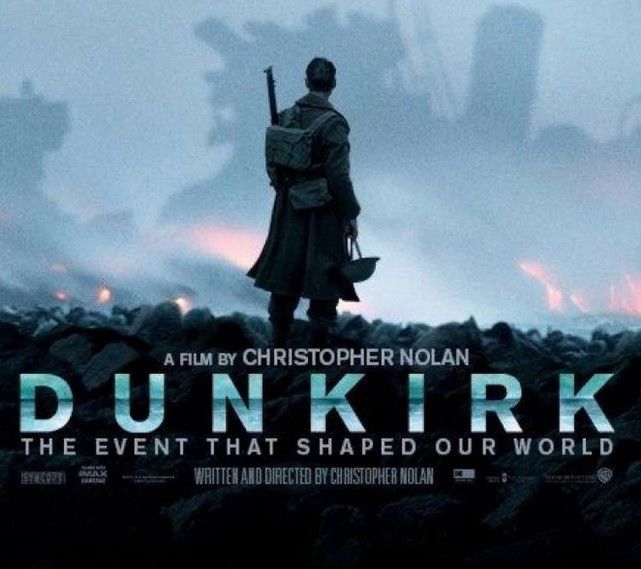

If you don’t know what a Stukka Dive Bomber sounds like, you will never forget its eerie, piercing wail after watching Dunkirk. It is sound, not gory acts of violence or stunning set-piece battle scenes, that builds and holds the sense of dread in the viewer and sets director Christopher Nolan’s latest feature film apart from contemporary portrayals of World War II in cinema.

Set in the spring of 1940, when the Nazi war machine was at its most indomitable, Dunkirk tells the story of Britain’s valiant, desperate operation to rescue 330,000 allied troops stranded on French soil. Facing down a German advance with only the sea at their backs, what remained of the British Army waited, with little hope, for salvation.

Despite the complexity and great stakes of such a large, storied operation, Nolan expertly conveys the grand narrative of the battle through the experiences of three individuals fighting and surviving in the three realms of the battle: land, air, and sea. Fionn Whitehead plays a British private stranded amongst thousands of others struggling at every turn to find a way off the beach. Tom Hardy is a Royal Airforce pilot fighting against time to clear the skies of German aircraft. Finally, Cillian Murphy plays a British officer rescued by a father and son captaining one of the several civilian boats sent to Dunkirk to aid in the rescue effort.

Unlike other World War II depictions that focus on personal bravery or the ties that bind soldiers in war, Dunkirk places the viewer in the constant, overwhelming and inescapable terror of battle. As each character struggles to survive, be it on land, air, or sea, he is constantly faced only with bad options. Be it in service of heroism or self-preservation, a character’s choice is always a bet against the odds, and the tension this creates permeates every scene from start to finish.

However, while the individual characters elicit empathy from the audience, Dunkirk is, in a way, quite impersonal. In a film with minimal dialogue, even utterances of the characters' names are rare. In the same way, the distinction between the French and British is brought up only three times; the Germans not at all. In fact, the viewer never actually encounters a German face - only the menacing painted iron crosses on Luftwaffe fighter planes and the sounds of German soldiers' bullets. The larger war in which the battle is fought is left off-screen; and while this sharpens the focus on the individuals' experience of the battle, it also dampens the near-legendary scene of small, recreational boats crossing the channel into a warzone, steely, defiant, stiff-upper-lip British civilians at the helm.

Though it is sound—and occasionally silence—that sell the pervasive fear, Dunkirk is a visual feat, and the opportunity to see it in IMAX or even 70mm should not be missed. From the stark and terrible beauty of the expanse of the English Channel to the tension and realism of Hardy’s dogfighting scenes, Nolan manages to capture the larger-than-life feel the story of Dunkirk has acquired over the last 80 years. For example, Nolan’s use of a custom camera rig and lens attached to Hardy’s Spitfire allowed an IMAX camera to film both the pilot’s face and his perspective through a cramped Spitfire cockpit. By avoiding CGI or green-screen trickery, the added effort pays off by preserving the authenticity of these scenes (though a keen-eyed WWII buff may catch that the German Bf-109 is in fact a repainted Hispano Buchon).

Compared to previous Nolan films with time bending narratives like Memento, Inception, or Interstellar, Dunkirk is a simpler story arc, though Nolan’s impeccable control of time and sequence to craft a narrative shine through here as well. He uses the shifts between the three narratives—each occurring over a different scale of time, sometimes minutes, sometimes days— to capture the massive scope of the Dunkirk operation without sacrificing the personal drama of each individual’s experience.

At just 106 minutes, it does away with character development and subtle exposition, leaving that to your ears and eyes. A very brief amount of opening text lays the scene, but the film mainly assumes the viewer already knows what happened at Dunkirk, and rather has come to understand the feeling of it. Rich and cacophonous sound, a score by Hans Zimmer that deftly switches between inducing terror and hope, and the expressive performances of actors in roles large and small convey the urgency and dire straits of each character.

Dunkirk winds down only in its final moments. Just as it opens immediately with the urgency and impending doom felt by its characters, it ends by capturing a different set of emotions – anticipation and fear, but also, hope. As two young privates read British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s famous words after the rescue – “We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender” - the survivors face fleeting moments of respite, uncertainty, and resolve as they embark on the long, inexorable path to victory.