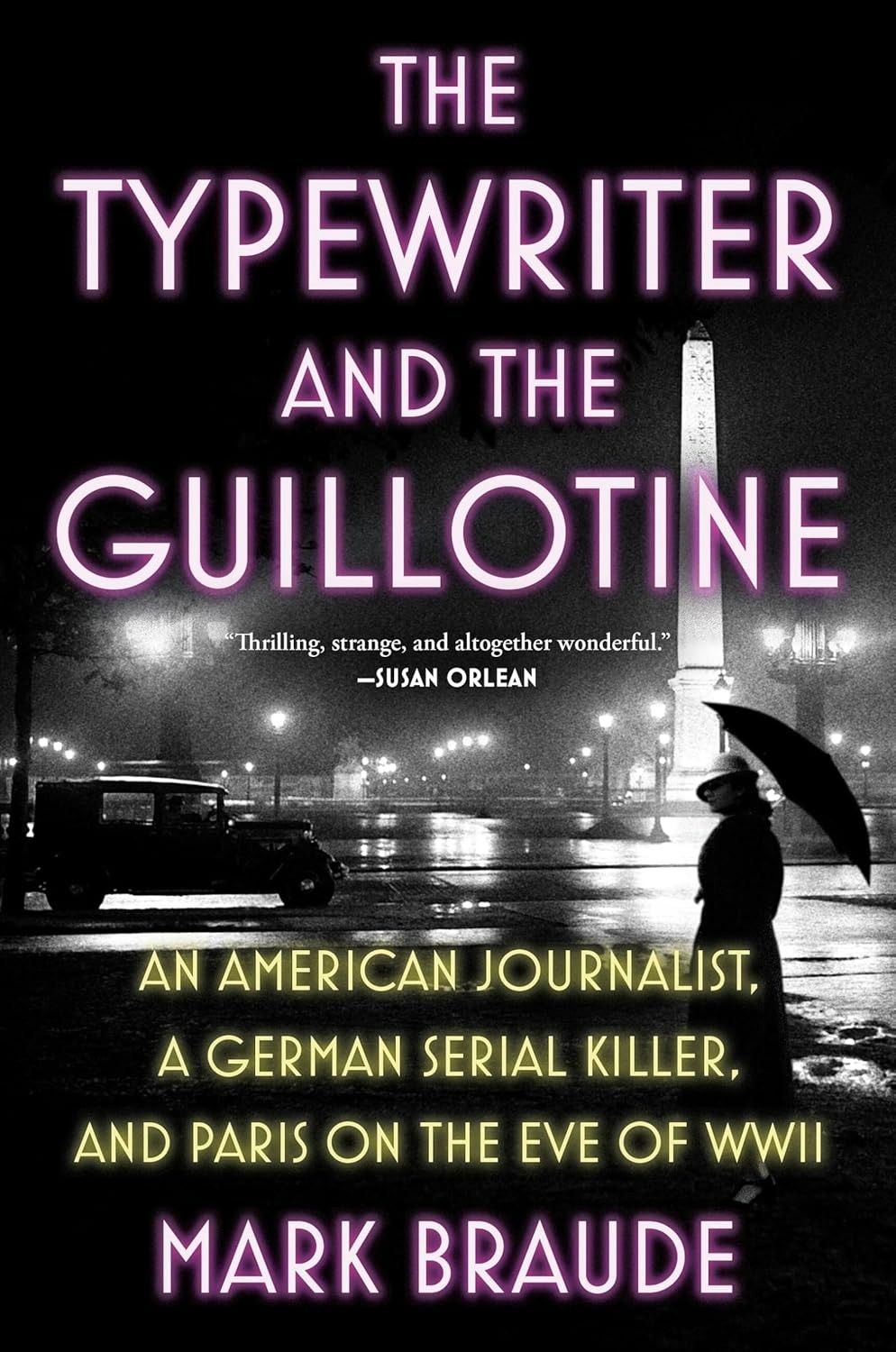

BOOK REVIEW: THE TYPEWRITER AND THE GUILLOTINE: AN AMERICAN JOURNALIST, A GERMAN SERIAL KILLER, AND PARIS ON THE EVE OF WWII

By Mark Braude / Grand Central Publishing

Reviewed by: Heidi Vierow

The Reviewer: Heidi Vierow, PhD, a retired CIA Clandestine Service officer, currently is an Intelligence Strategy and Policy Advisor at MITRE.

REVIEW — Paris in the 1930s, a female correspondent for The New Yorker based in France, and a German serial killer make for a compelling read of nonfiction. In The Typewriter and the Guillotine, Mark Braude interlaces the stories of Janet Flanner, an early contributor who penned the “Letter from Paris,” and Eugen Weidmann, a psychopath who was the last person publicly executed in France.

With 2025 being the 100th anniversary of The New Yorker, it is timely to read about how its founders, Harold Ross and Jane Grant, evolved the focus of the magazine in its early years to what it has become today. Flanner was among the early contributors, and she was lucky to have had Katherine White, E.B. White’s spouse, as an editor who could refine her piquant style. As a young journalist and essayist with a knack for identifying new trends and news in Paris that would interest a New York-centric audience, Flanner initially focused on societal, literary, and entertainment topics. She was friends with a wide circle of American expats as well as foreign writers and artists. Initially she kept the content of her pieces determinedly apolitical. Yet as war spread through Spain and fascism and Nazism rose in Europe, Flanner felt conflicted about taking on political and war reporting and shied away from these topics even when she covered the Nuremburg rallies and wrote a ground-breaking piece on Hitler. With the Stavisky Affair, the 1934 financial scandal that involved the French prime minister, she started writing about “warring ideologies in France, which meant writing about European diplomacy more broadly,” and she “interpreted (Ross’) silence as encouragement.” Braude depicts the various circles in which she moved, her wide European connections, and her drive to understand and relay to the American reader the evolving trends and news in these challenging and rapidly changing times.

Braude gives the reader a full sense of Flanner’s personal and professional sides. A lesbian, she had several long relationships, and she found freedom to live as she chose in France. He depicts well her evolution from a failed novelist, to an increasingly successful and confident correspondent on nonpolitical topics, and finally to a writer capable of explaining complex political movements and events without being an editorialist or propagandist.

Braude intersperses Flanner’s development as a writer with Weidmann’s devolution from a seriously troubled teenager to a remorseless killer. Despite his parents’ efforts to do what they could for him, Weidmann carried out a murderous spree that terrorized France. His guillotining attracted so many eager witnesses that five days later the French courts amended the law to prohibit public executions. The government banned the use of guillotine thirty years later.

Braude writes a compelling narrative that he has researched thoroughly. He recreates Flanner’s world in particular, in more depth than he does Weidmann’s, but the latter, though diabolical, was, in some ways, a simpler person with less narrative to relay. Flanner covered Weidmann’s trial, but it was one of many stories that she covered over a long career. Thus, the intertwined storylines feel uneven and forced, because Braude has more material on Flanner, the more multifaceted person of the two. His telling of Flanner’s story stands on its own merits; his book just needs a different title.

Unfortunately, Braude for some reason feels compelled to excuse Flanner’s antisemitism in her younger years. He attempts to explain it away as more of “arrogance and ignorance than … outright maliciousness.” In addition, when Flanner covered the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, Braude notes that she seems not to have interviewed any Black or Jewish American athletes in her extended reportage. He clearly appreciates who she became as a writer, but she was who she was, and his attempt to exculpate her perhaps arises out of some sense of duty to defend her. He does not excuse her other flaws, so his attempts on this topic are out of place.

At the end of the World War II after having interviewed a woman released from Ravensbrück and visited the concentration camp at Buchenwald, Flanner recognized the horrors inflicted upon Jews, and the camps haunted her. In her Nuremburg Letters, in which she covered the trials, she aimed to record the treachery inflicted by the Nazis, and Alfred Knopf, her publisher, praised it as the best he had read on the trial.

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business