BOOK REVIEW: THE SPY AND THE DEVIL

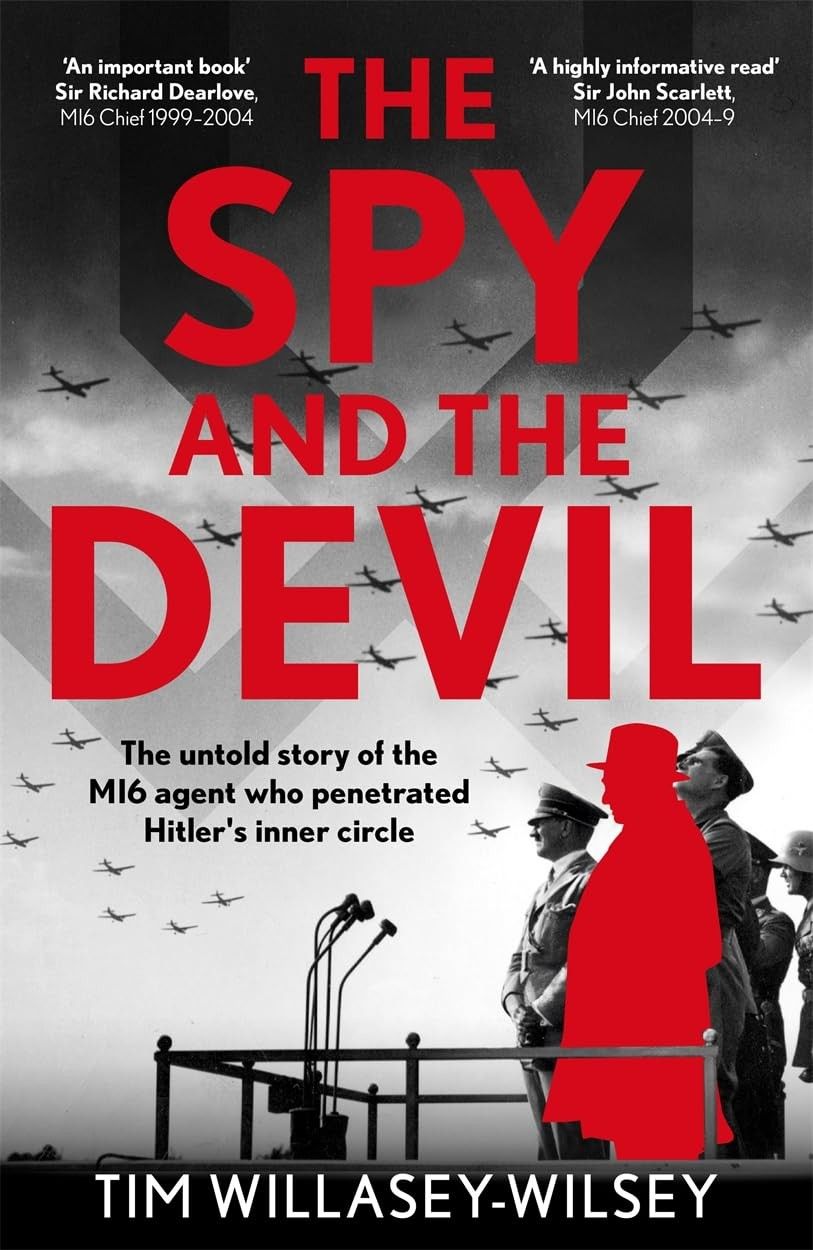

By Tim Willasey-Wilsey / Published in the US by Blink and in the UK by Bonnier

Reviewed by: Michael Smith

The Reviewer — Michael Smith is the author of The Real Special Relationship: The True Story of How MI6 and the CIA Work Together (with a foreword by former CIA Director, General Michael Hayden, and an introduction by former MI6 Chief Sir John Scarlett). Published in the US by Arcade and in the UK by Simon and Schuster

REVIEW — Britain and America had a number of agents inside Nazi Germany during the Second World War, but one of the most important of those spies has frequently been ignored, in part because in a world where agents are supposed to stay quiet even unto death, Bill de Ropp subsequently published details of his exploits that sounded impossible to believe.

Tim Willasey-Wilsey, a Cipher Brief contributor, spent many years working for the U.K. Foreign Office with a number of postings in Africa, Latin America and Asia and his expertise and experience is immediately apparent in his fascinating new book The Spy and the Devil. It reveals how de Ropp infiltrated himself into Hitler’s inner circle on behalf of MI6.

Baron Wilhelm Sylvester von der Ropp, born in Lithuania in 1893, was a ‘Baltic German’, a member of a landed class descended from Teutonic knights who had settled in the Baltic republics in the middle-ages and established large estates. But he was no fan of his heritage and as simple Bill de Ropp decided to travel, eventually acquiring a British wife and settling in a quiet Wiltshire village.

As the First World War approached, and anti-German feeling soared, de Ropp’s linguistic ability, he could speak German, Russian, French and English without a trace of an accent, and his determination to fight for Britain, protected him from local opprobrium. He was granted British citizenship in 1915 and joined the Royal Flying Corps. After a brief period flying balloons on the Western Front he moved into the intelligence world, taking charge of interrogations of German prisoners-of-war in France and the UK. ‘It was there that I learnt the delicate art of obtaining information without appearing to seek it,’ he later said.

De Ropp, who had joined the Mayfair-based Savile Club, took great pleasure in being a fully paid-up member of the British establishment and in April 1919, he offered his services to MI6, becoming an agent of Stewart Menzies, a future MI6 Chief. His ability to speak flawless Russian meant that initially he spent a lot of time travelling in the Baltic republics under journalistic cover, and it was there that he produced the first of his many coups, posing as the mysterious Captain Black, who commissioned a White Russian fraudster to produce “the Zinoviev Letter”, supposedly orders to the British communist party from Grigory Zinoviev, the head the Comintern, which controlled communist parties abroad.

The letter claimed that the Labour government’s attempts to improve ties with Moscow would radicalize the British working class and called on the British communists to ramp up their efforts to undermine the armed forces. Willasey-Wilsey makes a convincing case that initially Menzies, a prominent supporter of the Conservative Party devised the operation to support government policy but that it was “a classic case of mission creep. An operation initially designed to support a government objective gradually became a broader attack on UK-Soviet relations before finally being used against the Labour party itself.” The letter produced weeks earlier was released to the press on the eve of a snap election on 29 October 1924 which Labour lost. More than a century later, it remains deeply controversial.

The Cipher Brief brings expert-level context to national and global security stories. It’s never been more important to understand what’s happening in the world. Upgrade your access to exclusive content by becoming a subscriber.

But it was against Germany that de Ropp became most useful. He moved there in the mid-1920s, ostensibly as the Berlin representative of the Bristol Aeroplane Company and was soon introducing visitors to the city’s famously scandalous nightlife, often accompanied by Frank Foley, the MI6 head of station in the German capital. Although Foley passed on de Ropp’s reports to London, he did not control the operation which was run from the very top. Willasey-Wilsey quotes one veteran MI6 officer, familiar with the historical files, as saying that it was one of only two cases run solely by the MI6 Chief in the 1920s.

The mission in Berlin was to infiltrate the up-and-coming Nazi party and find out their plans. His cover was as a correspondent for The Times (of London). He adopted the position of a sympathetic Briton with links to pro-Nazi supporters in the British establishment, notably including senior Air Ministry officials. De Ropp’s initial target was carefully chosen. Alfred Rosenberg, who had temporarily led the party when Hitler was in jail in the wake of the Munich Beerhall Coup, was no longer a prominent member of the leadership but remained personally very close to Hitler.

Willasey-Wilsey describes de Ropp’s cultivation of Rosenberg as “a masterclass in espionage, demonstrating that Bill possessed innate skills as a spy.” Rosenberg, now head of the Nazi party’s foreign policy office, even asked him to be his adviser on British affairs. When de Ropp casually mentioned to Rosenberg in early 1931 that he and his wife were going to be staying at Garmisch, the winter resort close to Munich where Hitler was still based. Rosenberg took the bait: “Would you like to meet Hitler while you are there?”

It was an extraordinary meeting. Hitler immediately cut to the chase. “What do the English think of my movement?” to which de Ropp honestly replied: “They say that a great deal of what you preach is justified but that you are too radical,” a response that he subsequently felt might have been too blunt. But to his astonishment Hitler asked to meet him again and suggested that de Ropp act as his confidential adviser on the British. His German advisers were too inclined to tell him what they thought he wanted to hear, he said. ‘If you could keep me informed of what, in your opinion, the English really think, you will not only render me a service, but it would be to the advantage of your country.” It was to be “a gentleman’s agreement between two soldiers.”

Some outstanding research has uncovered one of the greatest untold stories of the Second World War intelligence. I will avoid any spoilers on the excellent and extremely useful intelligence de Ropp produced, although there is a current resonance in that it was frequently ignored because it was not what the politicians wanted to hear.

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business