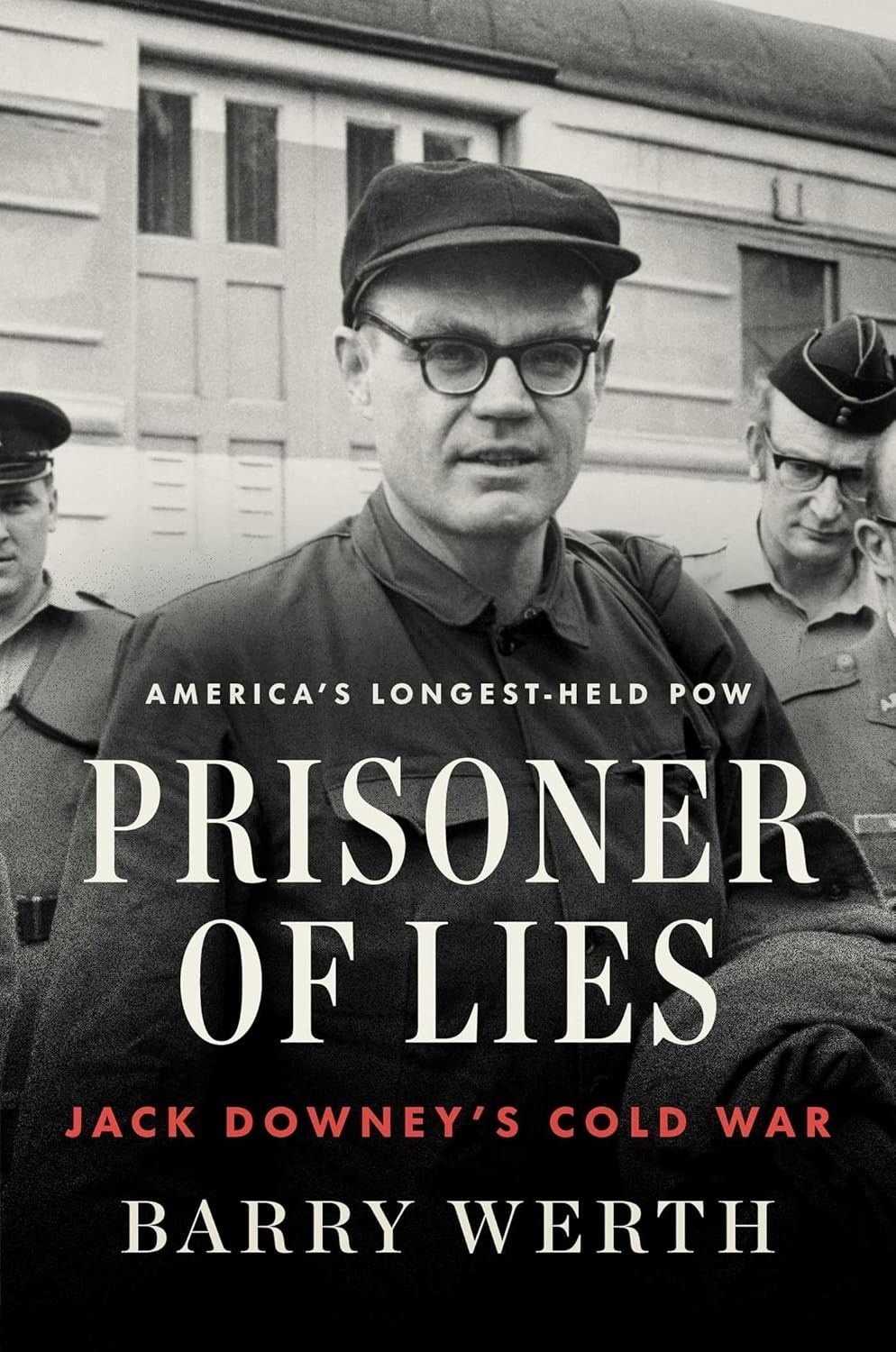

BOOK REVIEW: Prisoner of Lies, Jack Downey’s Cold War

By Barry Werth/Simon & Schuster

Reviewed by: James L. Bullock

The Reviewer — James L. Bullock is a retired senior Foreign Service Officer, with over forty years of U.S. Government service, as a naval officer, a US Information Agency employee, and as a State Department diplomat. He graduated from Yale College in 1971, twenty years after Jack Downey. Yale changed greatly over those twenty years, but much also remained the same.

REVIEW — This book is a story that took far too long to appear.

Jack Downey was a bright-eyed, Irish-Catholic boy (“not shanty, not lace-curtain”) from Wallingford, Connecticut, who went to a tony prep school (Choate) and then on to Yale on scholarship, where he was a football player, wrestler and aspiring gentleman. He graduated with a major in English in 1951, a poster child for the Silent Generation, as America emerged from the Second World War convinced it could and should lead the world. Institutions such as Choate and Yale were understood to be where America’s leaders were formed, and that is where the newly established Central Intelligence Agency recruited many of its new officers.

Prisoner of Lies: Jack Downey’s Cold War relates three compelling stories: Downey’s “great expectations” before he joined the CIA, his time at the Agency – two decades of which he spent in a Chinese prison, and his post-release rehabilitation – when he returned to finish the life he’d planned so many years before.

Author Barry Werth, about twenty years younger than Downey, is no stranger to the world of New England prep schools and the Ivy League, although he himself is a product of SUNY and Boston University. In his research for Prisoner of Lies, Werth collected an enormous amount of anecdotal material at Choate and Yale, and he does a good job of capturing that Yale of yesteryear, when maids still cleaned student rooms, and an all-male student body still wore blazers and ties to class. In 1951, according to Werth’s classmate Ambassador James Lilley roughly ten per cent of their class of 1,000 was recruited by the CIA. That was the Yale – now long gone - that lived on in Downey’s head during his captivity in China.

Prisoner of Lies is really more a work of journalism than of history. It reads easily, galloping through the Cold War years with anecdotes that summarize events that most of us who are old enough can generally remember, adding interesting teasers (were Allen Dulles’ wife and wartime mistress both really patients of Carl Jung? Did Robert F. Kennedy really once serve as counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy? Was Yale’s Whiffenpoof Song really the unofficial anthem of the OSS?) Whatever.

The narrative flows; but, even with end notes and an extensive bibliography, this is not academic writing. The journalist’s craft is evident.

The Cipher Brief Threat Conference is happening October 5-8 in Sea Island, GA. The world’s leading minds on national security from both the public and private sectors will be there. Will you? Apply for a seat at the table today.

Jack Downey’s imprisonment in China for twenty-one years is the backbone of Werth’s book, based on a prison memoir that Downey himself wrote after his release. (It was eventually published by his family in 2022, after Downey’s death in 2014, as Lost in the Cold War/Columbia University Press.)

Much of the narrative in Prisoner of Lies, however, follows the headlines over Downey’s years in captivity, providing an historical timeline against which the reader can measure Downey’s relatively constant, mind-numbing ordeal as an unacknowledged prisoner-of-war. Others were captured and released, but Downey’s fate was linked to domestic U.S. politics and a public admission that he was CIA. That had to await Nixon’s opening to China. The reader’s attention is repeatedly shifted from Downey’s cell to the world stage, and then back to that tiny cell.

A brief author’s note and prologue provide the basics: during the “police action” in Korea and less than two years after Mao Zedong declared the creation of the People's Republic of China, a promising Yale senior, looking to “be something important,” was recruited by the CIA.

A little more than a year later, after basic training that did not include Chinese language study, Downey was on an ill-planned “agent extraction” mission over Manchuria that was compromised. He was shot down and captured. Downey never should have been on that plane, and his capture was an embarrassment to the agency. Along with the State and Defense Departments, they scrambled to invent an alternative story. Downey’s mother received a letter of condolence, on CIA letterhead stationery, saying that her son “may have been lost,” but she was not allowed to keep the letter.

And so began the saga of Jack Downey’s long imprisonment, the longest of any American POW in history, although he was never formally acknowledged to be a prisoner of war.

Given that Downey’s own memoir was published just four years ago, Werth clearly set out in his book to provide context for that memoir, and he did so by digging up student and family memories and by retelling the news over all those years (Korean War, Joe McCarthy hearings, Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, the Uprising in Hungary, the shooting down of Gary Powers’ U-2 spy plane, Vietnam, Black Panter Trials, Watergate and so on...)

Some of these historical references tie to Downey’s case, but not all. Politics is a contact sport, and Werth clearly enjoys the re-telling.

Much of Prisoner of Lies is built around reminiscences by Downey’s Yale classmates, and there are many fleeting references to Yale campus landmarks. This reviewer (Yale Class of 1971) had no trouble with that, but a non-Yalie might be a bit lost at times. This also applies to references to events and individuals linked to the CIA. On that note, I confess that I was a bit puzzled when Werth included a reference to the October 23, 1983, bombing of the Marine Corps barracks in Beirut, but not to the earlier Embassy bombing on April 18 that killed eight CIA employees, including Near East director Robert Ames, the Station Chief, and most of the agency’s Beirut staff.

Whatever. If Downey’s personal story is the meat, then all of the historical material and the Yale anecdotes are still tasty stuffing.

Watch The World Deciphered, a new weekly talk show from The Cipher Brief with expert commentary on national and global security available exclusively on The Cipher Brief’s YouTube channel. Subscribe today.

What comes next, though, is perhaps the most interesting part of Prisoner of Lies: Part Three, the story of how Jack Downey rebuilt his life after being released. He came home, saw his mother before she died, reconnected with his Yale friends, went on to law school (Harvard, because Yale, inexplicably, would not take him), married a Chinese American classmate, had a normal family life, got involved in Connecticut politics, and became a juvenile court judge. How many of us could return after twenty-one years in a Chinese prison and so readily just pick up our hopes and dreams where we left off?

Bottom Line: I thoroughly enjoyed the read, even if following fifty-odd years of post-WWII American history “from 10,000 feet” sometimes left me a bit breathless. Werth clearly felt that Jack Downey deserved to have his story told sympathetically and in a broader context, and in that the author succeeded. I am left with some questions: Were all of the historical conclusions completely accurate? Did Werth lionize Downey perhaps a bit more than warranted? Are there lessons for us in Downey’s “three lives,” or was his experience limited to times and places we no longer share?

The book ends with a recounting of the Yale Class of 1951’s sixty-fifth reunion, two years after Downey’s death.

As the Whiffenpoofs’ song explains:

We are poor little lambs

Who have lost our way…

Gentlemen songsters off on a spree

Damned from here to eternity

God have mercy on such as we.

Baa! Baa! Baa!

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Interested in submitting a book review? Send an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com with your idea.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.