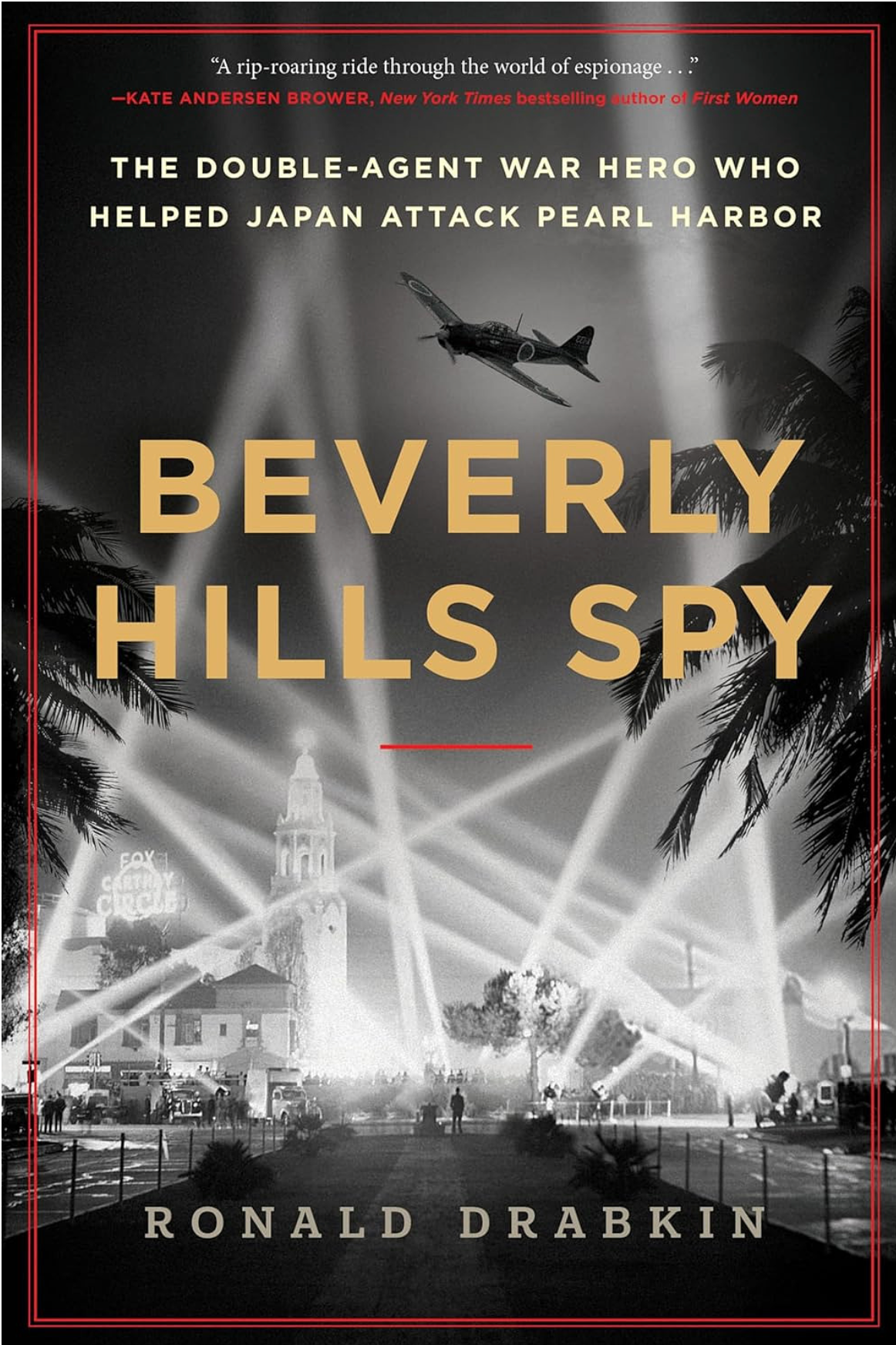

BOOK REVIEW: Beverly Hills Spy

By Ronald Drabkin/ William Morrow

Reviewed by: Joseph Augustyn

The Reviewer - Joseph Augustyn is a veteran of the CIA’s Directorate of Operations, and served as Deputy Division Chief of East Asia Division. He is also a Cipher Brief expert.

REVIEW - Beverly Hills Spy by Ronald Drabkin is the story of Frederick Rutland, a World War I British aviation hero…and perhaps the most important and influential spy of the 1920’s and 1930’s. Most people know little, if anything, about him.

Rutland was the first pilot to take off and land an airplane on a ship during the battle of Jutland, the largest naval battle of the First World War. “Rutland of Jutland’s” media fame as a daring and swashbuckling aviator was real and deserved, and he captured the imagination of a British public hungry for stories of heroic figures.

Adding to his acclaim was the account of Rutland diving into the sea, against orders, between two ships to save a shipmate who had fallen overboard while being evacuated from a sinking ship. Rutland was everything a British hero should be…until he wasn’t.

As Drabkin recounts, Rutland would become a devious and calculating spy who not only betrayed his homeland, but also Britain’s western allies by helping the Japanese plan their attack on Pearl Harbor.

So, who was Rutland, really? Drabkin has written an engaging, well-sourced and detailed account of the man who was born into poverty, the son of a day-laborer, and who was an elementary school dropout. Drabkin cleverly and convincingly describes how Rutland rose through the ranks of the British Navy because of his perseverance, manipulative personality, charisma and most importantly, his uncanny ability to grasp, learn, and retain technical data related to aviation and aircraft carrier design.

After the Great War, Rutland became a sought-after expert, especially by the Japanese. Yet, according to Drabkin, Rutland had fatal flaws that surfaced primarily after he was passed over for promotion by the Royal Air Force because of his “common” upbringing. Rutland never forgot that slight. Like so many traitors throughout history, a bruised ego led him to betray his country.

It's not just for the President anymore. Are you getting your daily national security briefing? Subscriber+Members have exclusive access to the Open Source Collection Daily Brief, keeping you up to date on global events impacting national security. It pays to be a Subscriber+Member.

In 1922, Rutland walked into the Imperial Japanese Navy Office in London and said he was “interested in exploring new opportunities.” Money and adventure motivated him, and the Japanese were eager to accommodate. They wanted to learn all they could about British naval aircraft and carrier design technology, so Rutland was off to Japan with his wife and family.

While there, Rutland embraced Japanese culture, built a network of senior Japanese naval officers, and lived a life of conspicuous wealth. As Drabkin explains, Rutland’s ego and desire to remain in the spotlight that he first enjoyed as a British war-time hero, was obvious to the Japanese, who patiently played to Rutland’s personality. While MI5 in London was on to him quickly, Rutland maintained that he was only working for Mitsubishi, and not the Japanese Government. Regardless of his publicly stated affiliation, throughout his life Rutland remained in a constant state of plausible denial. In fact, he was literally helping the Japanese modernize its navy.

In 1933, the Japanese, who Drabkin says were well into war preparation mode by that time, convinced Rutland to move to Los Angeles to serve as an intelligence agent. Playing into Rutland’s vanity, the Japanese provided Rutland with lavish accommodations in the United States and huge sums of money, tasking him to develop relationships within the aviation and U.S. Navy communities. Los Angeles was home to companies like Boeing, Lockheed and Douglas, and who better to infiltrate the social and professional circles in LA than a decorated WWI British aviation hero? Rutland was in his element.

Living lavishly in Beverly Hills, Rutland thrived in a lifestyle most spies only dream about. He befriended the head of the West Coast Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), Hollywood icons like Boris Karloff and Charlie Chaplin, joined expensive and elite private clubs, and negotiated a salary from the Japanese worth ten times that of the highest paid Japanese admiral. And, as Drabkin shows, it turned out to be an excellent investment for the Japanese. Rutland funneled to Tokyo information about aircraft technology, U.S. troop and fleet movements and, eventually, Rutland even established his own small network of spies on the West Coast, including one living and reporting directly from Pearl Harbor.

Much of Beverly Hills Spy focuses on how Rutland juggled his espionage and personal life, from his Hollywood connections, to his family (especially his devotion to his daughter) and his globetrotting escapades. Drabkin says Rutland wanted to prove his worth to the Japanese, and to reassure himself, in the end, that he was and would remain the most important aviation and naval expert in the world.

The Cipher Brief hosts expert-level briefings on national security issues for Subscriber+Members that help provide context around today’s national security issues and what they mean for business. Upgrade your status to Subscriber+ today.

Drabkin describes how Rutland befriended the ONI rep and how Rutland led him to believe he was actually working secretly as a double agent for the US Government. Drabkin also elaborates on what was a strained relationship between ONI and the FBI, both in Los Angeles and in Washington, and the ineffective sharing of counterintelligence information between MI5 and MI6 and their counterparts in the U.S..

Everyone seemed to believe that Rutland was involved in espionage, but no one could prove it. According to Drabkin, Rutland did what any successful and productive spy under suspicion might do…he confused everyone he dealt with into believing he was working for them.

Drabkin is best when describing Rutland’s personality and motivation. He concludes that, in fact, Rutland was indeed a “bad guy,” despite Rutland’s conciliatory behavior and pledge of loyalty to the British Crown in the immediate wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Drabkin is especially adroit when pointing out Rutland’s personal failings and the characteristics that made him a spy in the first place. Rutland’s huge ego, his desire for fame and wealth, and his delusional belief that he was smarter than everyone else was his downfall. Combined with the ignominy Rutland felt after being shunned by the British Navy after WWI, it was the perfect storm.

Rutland was sentenced to prison by the British after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was released in December 1943, and lived the remainder of his life in a small Welsh village. Rutland would never admit to himself that he had ever done anything wrong. He died by suicide in 1949 in his apartment after inhaling gas from his cooking stove.

In the Beverly Hills Spy, Drabkin has written a work that sheds new light on a little-known spy, and insights into the sophisticated and successful Japanese intelligence gathering network between the two World Wars. For this, Drabkin is to be congratulated.

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Interested in submitting a book review? Send an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com with your idea.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief